Lessons from History: The 1990s Semiconductor Cycle(s)

The 1990s was the birth of the modern world order

If the main character of the 1980s was Japan, the main characters of the 1990s were Korea and Taiwan. I regret not discussing Korea’s rise at the end of the last decade, and it might have been better to put them there. But conceptually, I thought talking about the “rising tigers” would be much better to discuss here in the 1990s when they took flight.

A great book about the rise of other Asian countries in semiconductor manufacturing is “Tiger Technology,” which is an extraordinarily dull but convincing read about the impact of Governments fostering the rise of Korean, Japanese, and Taiwanese manufacturing. I reference multiple numbers from the book - and If you are interested in a dry history lesson, this is the book for you.

So let’s set the scene, the late 1980s were a bit of a relief for the industry. On the one hand, the crisis of DRAM dumping had passed, and the American companies, in particular, improved their process and technology. But, on the other hand, the strong end years of the 1980s led to a relatively calm period of continued growth, which inflected to strong growth years in the early 1990s.

Revenue growth was more sluggish in North America, but the rising tigers (Korea and Taiwan) grew extremely fast in the early 90s. One of the reasons was a robust domestic economy, but since Semiconductors would end up as their primary export, this might be a circular argument. The real reason was taking share from the donor Japan. Additionally, the government heavily overbuilt the semiconductor industry through joint ventures and lending schemes.

Japan’s supernova last decade became a slow slide into deflation by the end of the 1990s, just in time for Korea and Taiwan to begin their economic miracle. But the rising Tigers didn’t have a smooth ride, and by the end of the decade, there was an Asian financial crisis. This impacted everyone, especially Korea - one of the epicenters of the crisis. The glut of loans could partially have been one of the drivers to creating the oversupply in memory Capex that wrecked the industry in 1996-7.

Regardless the 1990s were a fantastic decade for Taiwan and Korea in particular. Below are some examples of their absolute financial dominance. TSMC grew revenue almost 3x in 2 years, while the entire industry grew 74% in 2 years!

Korean Memory grew 8.3x times over from 1991 to 1995! That’s quite an impressive CAGR. But unfortunately, this was partially funded by the government and chaebols in a close interconnected web of affiliated parties and loans that would eventually lead to a collapse.

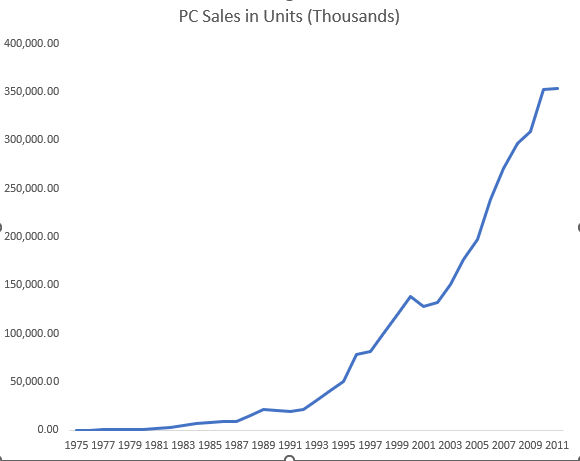

Beyond macroeconomics and emerging economies in the 1990s, the computing paradigm was most definitely the PC. The transition to PC’s mainstay as a dominant computing platform happened sometime in the early 1990s, and IBM, the mainframe maker, didn’t manage to keep up. I didn’t mention the PC in the 1980s piece because it frankly was a niche market! The mainframe was the king of computing back then, but I think the 1990s is when the PC came into its own.

The mainframe would have its place in the world for a long time but at a much slower rate of growth and a smaller percentage of the total computing pie. The new driver of growth was PC primarily. The industry went from ~20 million units to over 138 million units by the decade's end.

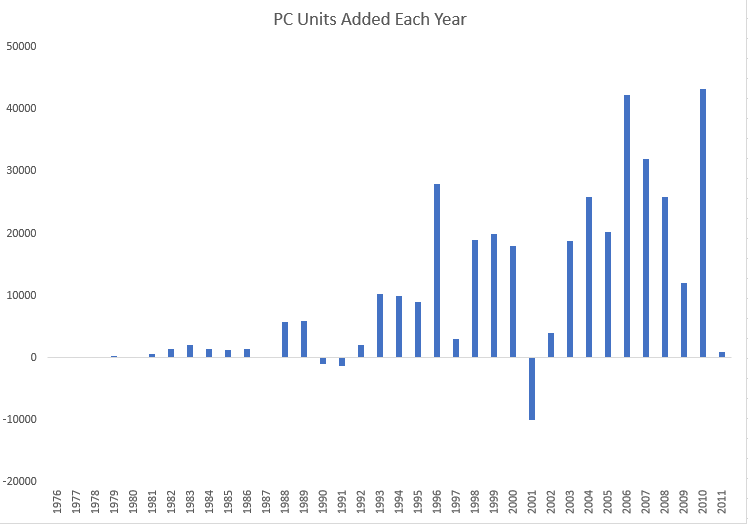

This chart looks exponential, so I want to translate it into units added each year. This chart should be familiar if you’ve read the better framing S-Curves piece. The first big initial wave of PC adoption occurred in the late 1990s.

The big exponential curve was mainly in the late 90s for PCs. And the PC story will dominate this entire decade and even into the early 2000s. For semiconductors, the 1990s were a true heyday that was unmatched until the next platform that would rise almost 20 years later, the smartphone. But enough about the big picture, let’s walk through semiconductor history yearly. Given my data sources, this will be a US-centric timeline.

1990-1991: In Between Years

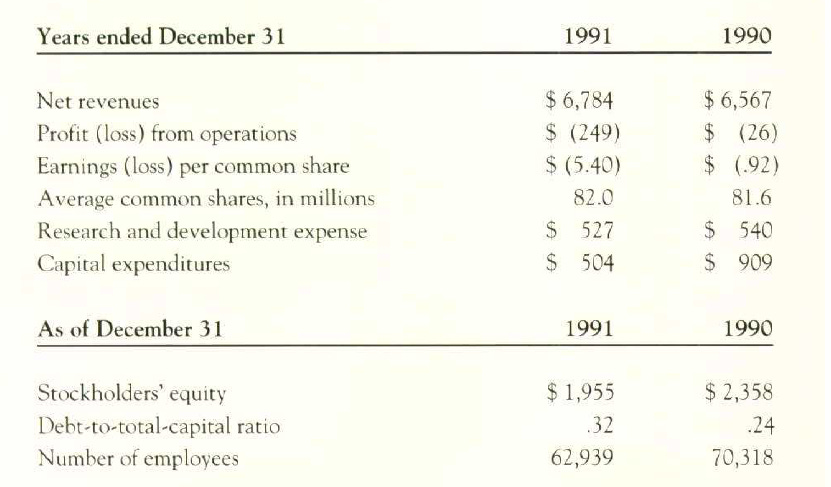

1990 was not a great year for the United States. While Taiwanese and Korean startups thrived, domestic companies’ revenue was flattish to slightly up, but economics eroded. Revenue was up broadly for the industry, but profits were down. Refer to the results of National Semiconductor below.

But if we look a bit more granularly, the end markets vary. Information Processors were flat year over year, while Personal Systems grew meaningfully. The PC was still in its infancy and growing fast. Below are IBM sales by segment.

But if you look to other players like Texas Instruments, they were not doing as well. The entire defense industry was starting to slow off at the end of the Cold War, which moved the defense industry from a growth industry to a maintenance industry. As a result, multiple companies began transitioning from the all-important defense end market and pivoting into more consumer-focused products. At the time, this was one of the most critical end uses of semiconductor device types.

While 1990 would be a solid year of growth, 1991 was more challenging.

1991 was a recession partially caused by many reasons that would be familiar to readers today. First, in late 1990 there was an oil shock after Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait and restrictive monetary policy in response to ~5% annualized inflation in 1990. The massive overbuilding of the 1980s from the Savings and Loan crisis overhung parts of the early 90s leading to an economic contraction. These all rhyme quite a bit with today’s environment, and understandably the economy has started to turn.

The net result for semiconductor-exposed companies was terrible. Reminder for anyone whose reading semiconductors is a pro-cyclical business, so when the economy busts, the semiconductor industry also does.

Let’s turn to the companies at the time, starting first with TXN.

Revenue was up slightly but profits down massively. The same could be said for National Semiconductor and IBM. What’s interesting is that during this period, there was a different beat for other companies as Micron and Intel both posted excellent results.

Micron was marching to the beat of a different drum, as results were up meaningfully, and they posted meaningful operating profits.

The big reason for the increase in revenue was primarily a new product launch of the 1 Meg DRAM, but pricing in DRAM was sluggish despite significant volume increases. Given the macroeconomic outlook, the outlook looked shaky at the August year-end.

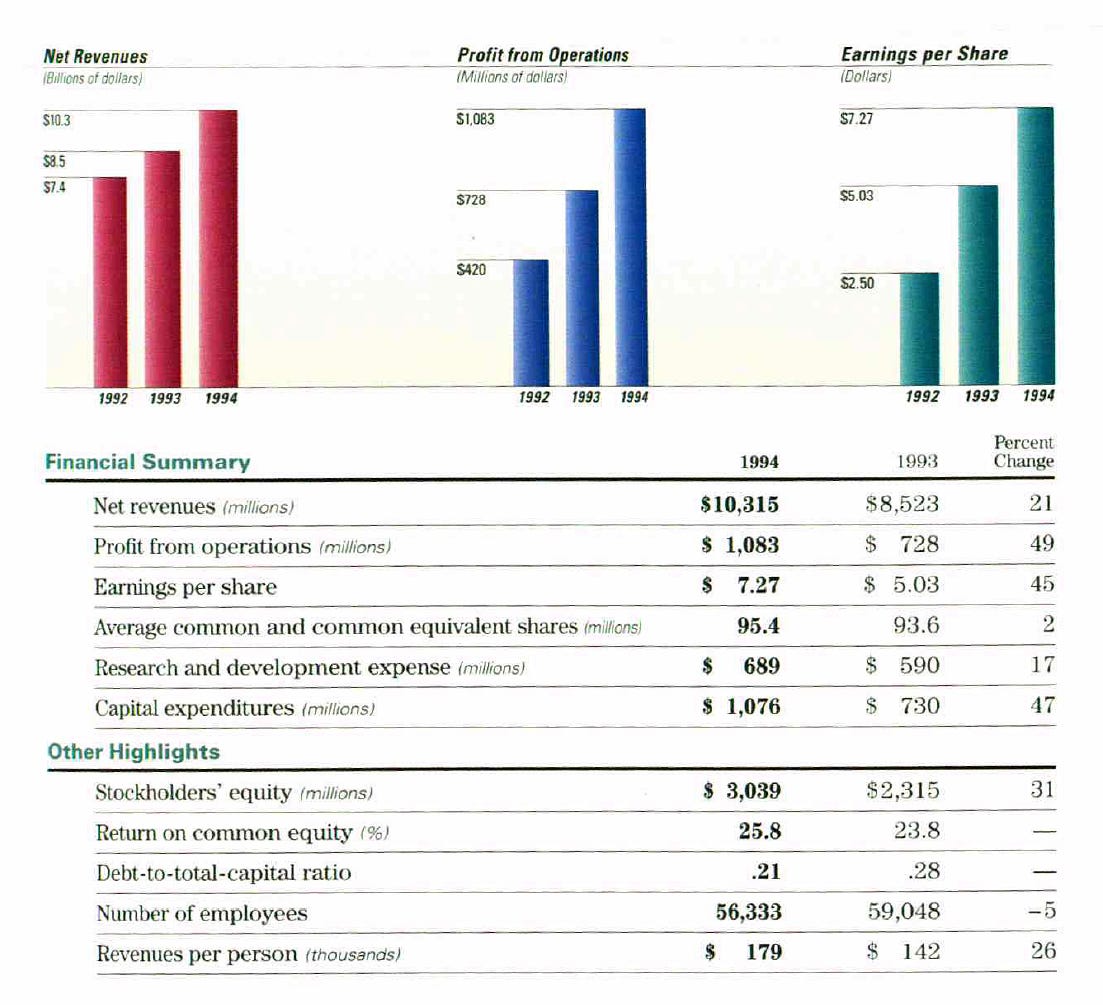

However, the last company I want to talk about that I haven’t spoken about despite its prominence is Intel. Intel shines in the 1990s as they grew through most of the issues (this is the 1993 report, but notice continued earnings per share and revenue growth for 1991). Intel increased as linearly as a semiconductor company can, and new product launches led to higher profits.

The big reason for this is a killer product. I mentioned at the end of the 1980s piece that they would go on to massive success during the subsequent product launches, and this was the hey-day of the microprocessor. Intel would ship the new and successful i386 to much fanfare, and the peak of this cycle was in 1991. Intel was beating to a different secular drum than the broader environment. Intel could do no wrong, which is a recurring theme for the rest of the decade.

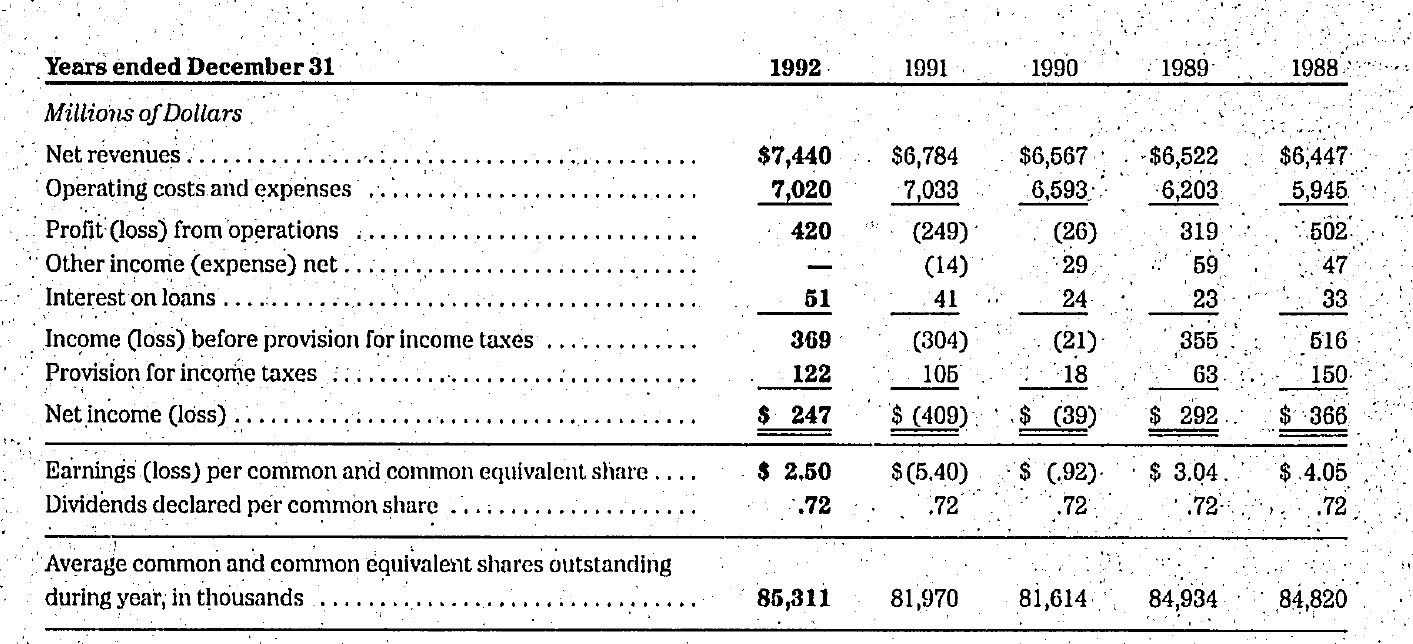

But let’s now move on to 1992. This year I want to focus on IBM in particular.

1992 - IBM’s Meltdown, a Slowing Economy

You wouldn’t recognize it now, but 1992 was one of the most challenging years for IBM. 1990 was the peak in revenue for half a decade, and the grinding problems at IBM became apparent in 1991 and 1992.

At this point, IBM was starting to suffer. Partially this was due to a bloated corporate structure, but more importantly, they seemed to have missed the paradigm shift from Mainframes to PCs. While they were tangentially related to selling hardware, the software they lost out to was a significant profit pool they missed. This software was, of course, MS-DOS and would lead to the dominant decade for Windows.

However, back at IBM, the stock started to flounder in the middle of 1992 and was in free fall by the end of the year. The stock got cut in half from 12.52 to 6.00 by January 1993.

I will take this brief time to talk specifically about IBM because they were the Apple of their time. A tightly integrated company that dominated many markets and was the 800-pound gorilla of the industry. But in 1992, they looked sick, becoming bloated, unfocused, and struggling to adjust well to the PC revolution amid a big mainframe business. Louis Gerstner would the CEO role in 1993 and begin its long turnaround into the end of the 1990s. This is one of the most remarkable tech turnarounds of the time.

In that process, IBM exited its semiconductor businesses of DRAM and hard drives, at this time focusing exclusively on software and services. IBM today still has a lot of legacy technology in the semiconductor space, but the loss of IBM, the semiconductor company, can be traced to this exact moment. For more information on IBM, I recommend reading “Who Says Elephants Can’t Dance” by Louis Gerstner. IBM would remerge, but never in its former glory.

I’m going to now turn to other companies like Texas Instruments. Results started to rebound in 1992 for TXN, driven by components up 20%, defense up 3%, and digital products up 1%. This was on the back of cost-cutting measures in 1991, so revenue and profits were up, unlike the last few sluggish years. At the time, TXN was focused on refocusing its portfolio from defense to DSPs and components.

So all was not lost; just IBM was. And on the back of a sluggish 1992, 1993 would be a staggering boom year as the economy started to grow again.

1993-1994 - Boom Times and the Beginning of the Shortage

First, let’s set the scene. After the recession of the early 1990s, the economy finally emerged from its slumber in a meaningful boom period post the oil crisis shock.

Amid the recovery, a large factory in Japan blows up, destroying 60% of the world’s specific epoxy called cresol used in semiconductor production. This terrifies the market, and there is a broad concern about shortages amid a strengthening demand environment. This sounds familiar to the current Covid-related supply crunch then boom but in a different format.

The result, of course, is a real semiconductor boom. Limited supply and strong demand create a self-fulfilling effect that supply additions can’t sate no matter how many new additions of capital. It was a perfect time in the industry.

Texas Instruments managed to grow 14% and 21% revenue, and earnings per share exploded.

Even sickly National Semi put up significant growth of 17% and 14% revenue! This was an excellent time for everyone involved and likely echo how the semiconductor market feels today. Below is a chart of utilization and profits, and it began to spike up in 1992 and kept high until the eventual crash in 1995. And crash it did in late 1995.

1995 - Fabrication Crunch

Please pay attention to this part in particular. If you get anything out of this post, it’s that the 1995 cycle was likely one of the better analogies we have to today. When we look at today’s process, there is no cycle that I think is a better match than the 1995 cycle. Some context from this excellent article.

The ramp-up of over 50 new fab lines in 1995 and 1996, which at first seemed incapable of meeting the insatiable demand for semiconductors, finally resulted in an over-supply of the commodity devices, DRAMs, in 1996. Fab delays occurred in cycles throughout 1996 and managers began making adjustments to spending plans almost on a quarterly basis. Capital shipments for equipment were put on hold for 6 months or more, for all but the most leading-edge equipment such as 248nm steppers, high-density plasma etchers, and chemical-mechanical polishing tools.

What happened during this period probably best closely mirrors what is happening today. Some of the language similarities are striking.

Debates over whether the cycle was over were around. This sounds like my very wrong 2022 outlook piece.

At stake is the outcome of a debate within the industry over whether semiconductor makers have left behind the boom-and-bust cycle that characterized the business until the last five years.

But like most things, this time was no different, and despite the impressive growth of 31%, 29%, and 40% for 1993, 1994, and 1995, the party did eventually end. In this case, it was a feed frenzy for new capacity and a fantastic time for the semicap companies. The 1995 cycle, in particular, was memory-driven, and of those 50 new fabs, many were memory companies.

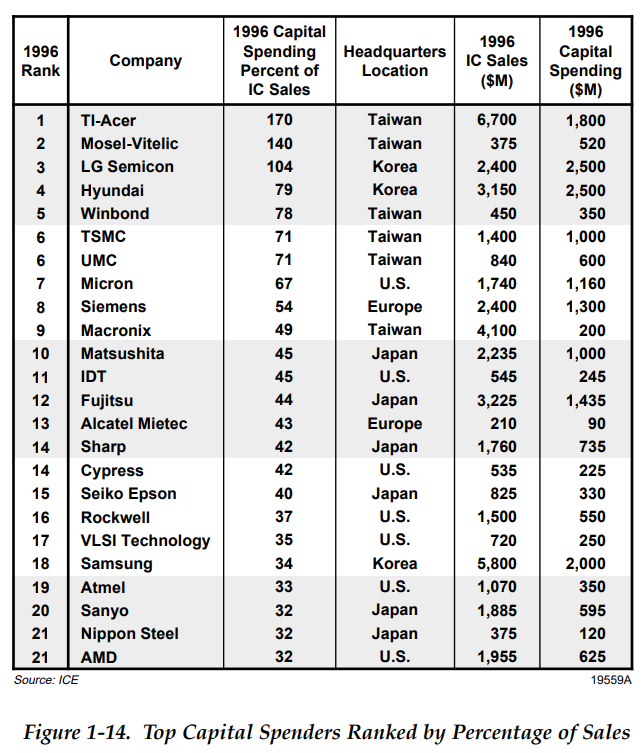

Capital expenditure bloomed as a percentage of the already booming semiconductor industry. Capital expenditures as a percentage of revenue peaked in 1996, which of course, was the cycle's peak.

These numbers have to be seen, as WFE Growth in 1996 was a staggering 74%!

Raw Capital expenditures show a crazy story - as Intel was spending the most, but as a percentage of sales, the Asian countries were investing in unheard-of ways. Today this is reminiscent of emerging Chinese semiconductor companies that are heavily investing in capacity.

But now, look at the percentage of sales to capex for Taiwanese and Korean firms. It’s no surprise that 1996 ended in a glut, and this has to be a perfect reflection of the Asian financial crisis to come.

If there ever was a chart to epitomize the stratospheric rise in Asian semiconductor companies, this is it. The beginning dominance of Taiwan starts in this decade, and it continues quietly into the 2000s and today.

The economics of a memory fab requires utilization to be high, even if they are selling products at a loss. The high fixed cost and ramping of a new node demand it. This predictably leads to a glut. Memory had the worst of it, and in 1996 we will see a drastic reversion of fortune.

1996-97 - Memory Woes and Asian Crisis

I want to start this with a simple graphic of the ASPs of 4M and 16M DRAM in 1996. Also, note the capacity utilization chart below - this was a brutal cycle. DRAM prices fell 75% in one year! That’s almost unheard of now, and utilization dropped from 95% to 86%. The operating profit unwinds brutally.

But this memory glut would go on for two years! From Micron’s annual report in 1997, they reported that:

The oversupply of DRAM in the worldwide market that began in late 1995 continued to affect the entire semiconductor industry in 1997. In fact, industry forecasters will predict that 1996-1997 will be the first time in history that the DRAM industry has experienced two consecutive years of declining revenues. Prices for DRAM fell by more than 75% during our fiscal 1996, then dropped another 40% during fiscal 1997.

The most staggering thing to me is that Micron managed to grow and keep a positive operating profit during this timeframe. This almost all came at the expense of Japanese companies, who began to exit the industry in droves. Samsung and Micron crushed the Japanese companies from the top and bottom ends of DRAM. I like the excellent video about Japanese semiconductors by Asianometry.

Micron did surprisingly well; the only company I have an annual report for. Micron’s revenue in 1995 and 1996 grew 81% and 23%, respectively, and operating income increased 108% and shrank 30% for 1995 and 1996. They even had a positive or breakeven cash flow this entire time!

I want to say that the entire industry was in pain, but if you look at Intel, it really didn’t seem like they were operating in the same industry. The Pentium was king, and Intel could do no wrong. As a result, revenue and operating income linearly increased year to year.

Companies like National struggled, while TXN began its commitment to completely refocusing its business on DSPs and analog. Intel was standing alone in its glory. It was ramping successive generations of processors, and each one would beat the previous in sales. Intel, for most of the 1990s, grew consistently and almost linearly.

This was likely Intel at its greatest, with Grove at the helm pushing new products onto the market that could ignore the cyclical nature of everything around them. Oh, how the mighty have fallen. But now I want to turn it back to the macro slightly.

Investing at over 100% of revenue was unsustainable, and the investment had to come from outside the companies. A perfect example is Samsung, whose tight interlinked Chaebol structure leads to shadow leverage. When the bust came from oversupplied Memory, the entire complex was weak. The continued loans for new investments for newer products led to the oversupply, figure, and eventual leverage collapse in Korea.

This impacted almost every Asian country, as contagion spread from currency. Eventually, the IMF created a package to stabilize Korea in particular, but the damage was done by then. For more reference, read the pretty decent Wikipedia article.

1998-2000 - The Internet Bubble

I get to leave this decade off on a high, almost bubbly note. I don’t think I have much to add regarding what the technology bubble was like in 2000, but it’s probably not the wrong time to discuss some of the companies. The results were strong, but the biggest acceleration was in the multiples paid for these companies.

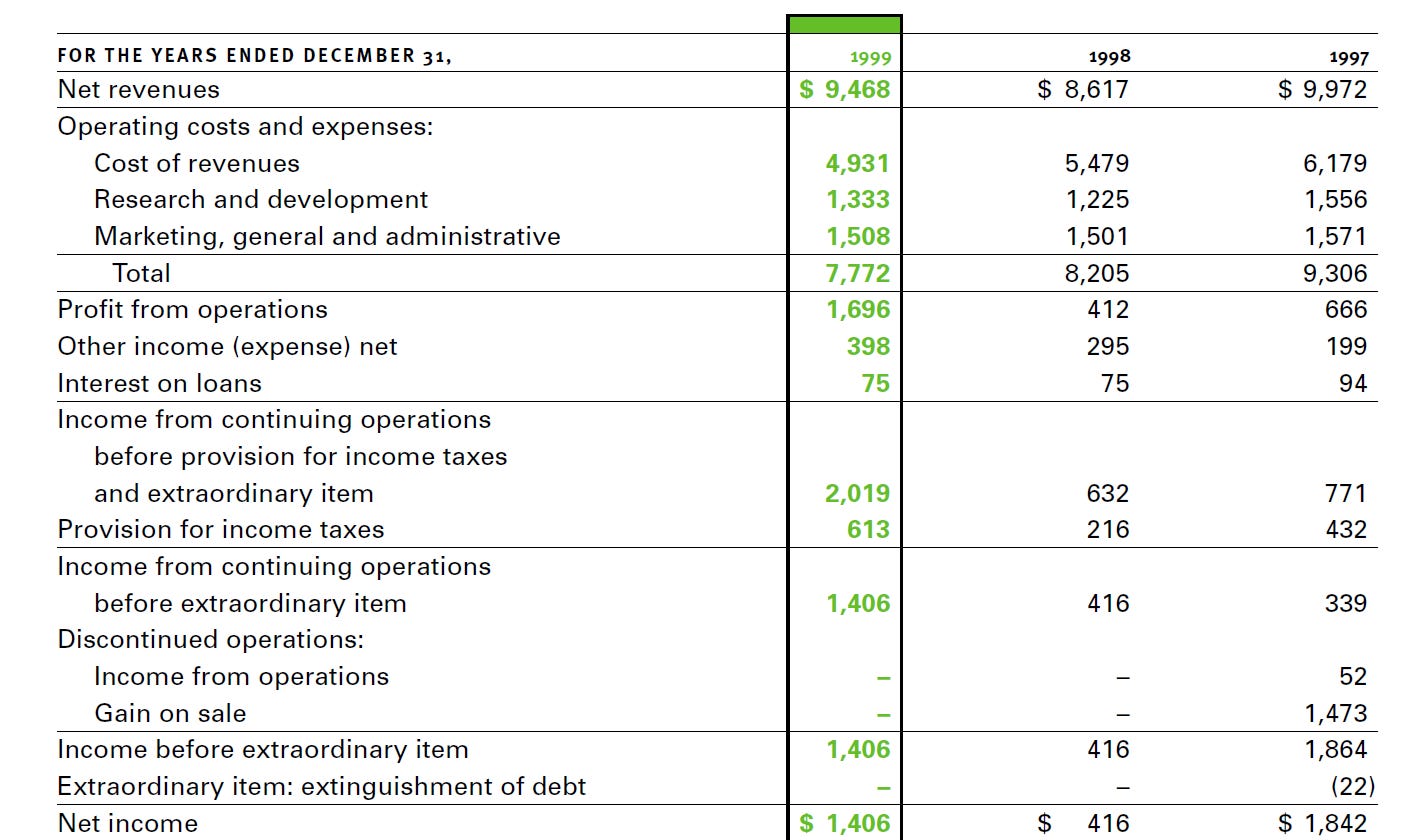

First, despite the rapid demand and energy toward technology, it’s pretty shocking to see semiconductor results not react in a way that is representative of the share prices.

Stalwart Intel did well but not great. Revenue and operating income grew, but that was nothing compared to the share price.

1998 was a mediocre year in the market, but companies like TXN rallied 90%! Talk about a divergence. That was surprising, given their share price did well in 1998 and even better in 1999.

Texas Instruments

National Semi

But, none of this matters because the bubble was in expectation, and the stocks, of course, rallied like mad. This would lead to a dramatic overbuild in telecom and other equipment, particularly in the 2000s, and it would take decades for many of these companies to achieve new highs.

I leave you there with the tech bubble, and the next time we will discuss the overbuilds, some of the early 2000s cycles, and of course, the GFC and logic overbuild. If the 1990s were the decade of PCs, the second half of the 2000s and 2010s were dominated by smartphones.

Conclusions

I think some of the overarching conclusions are looking at the rising economies. I can’t help but notice that the financials and spending remind me closely of China today. Chinese semiconductor companies frequently spend 100% of revenue on Capex, but the timeline, of course, is likely similar to catchup. If we linearly extrapolate their growth and spending, we should see Chinese companies become relevant in the latter half of the 2020s and maybe even become dominant in the 2030s. It will take a while, but the writing and analogy are for everyone to look at. Taiwan and Korea did it with a similar strategy in the 1990s; why not China?

The 1995 period looks like one of the most apparent analogies to the 2022 cycle, which looks to be ending. Even with an insatiable supply, a question of semis is still cyclical, the end always happens, and inventory gluts lead to a downcycle. We are seeing that happen today. While the staggering amount of investment is likely similar, I think, unlike then, we are a bit more consolidated than in the past. The DRAM runaway investment train is nothing like 2022, where Micron is almost instantly willing to cut supply growth to prop up demand.

It’s glaring to see the difference in DRAM today and then. DRAM has managed supply and demand growth well with the other public companies, and the lessons learned from the 1995 cycle probably is still remembered. Now logic builds, on the other hand, remain to be seen - and that will be something I explore in the 2000s.

Links and Relevant Sources

https://smithsonianchips.si.edu/ice/cd/CEICM/SECTION1.pdf

https://jeremyreimer.com/rockets-item.lsp?p=137

I’m putting the annual reports behind a paywall - but you can download them if you’re a subscriber! Thank you.