Lessons from History: The Great Railroad Buildout

History doesn't rhyme, it just repeats itself with increasingly strained analogies

It’s time for another history lesson—this one reaches further back than my usual fare. I spent months in books and unusual places on the internet for this piece, and I think I find the parallels to today’s AI buildout remarkable.

This is the story of the railroad capital cycle: how America financed, built, overbought, and eventually consolidated the most transformative infrastructure of the 19th century.

Early American History of Railroads: The Civil War and Land Grants

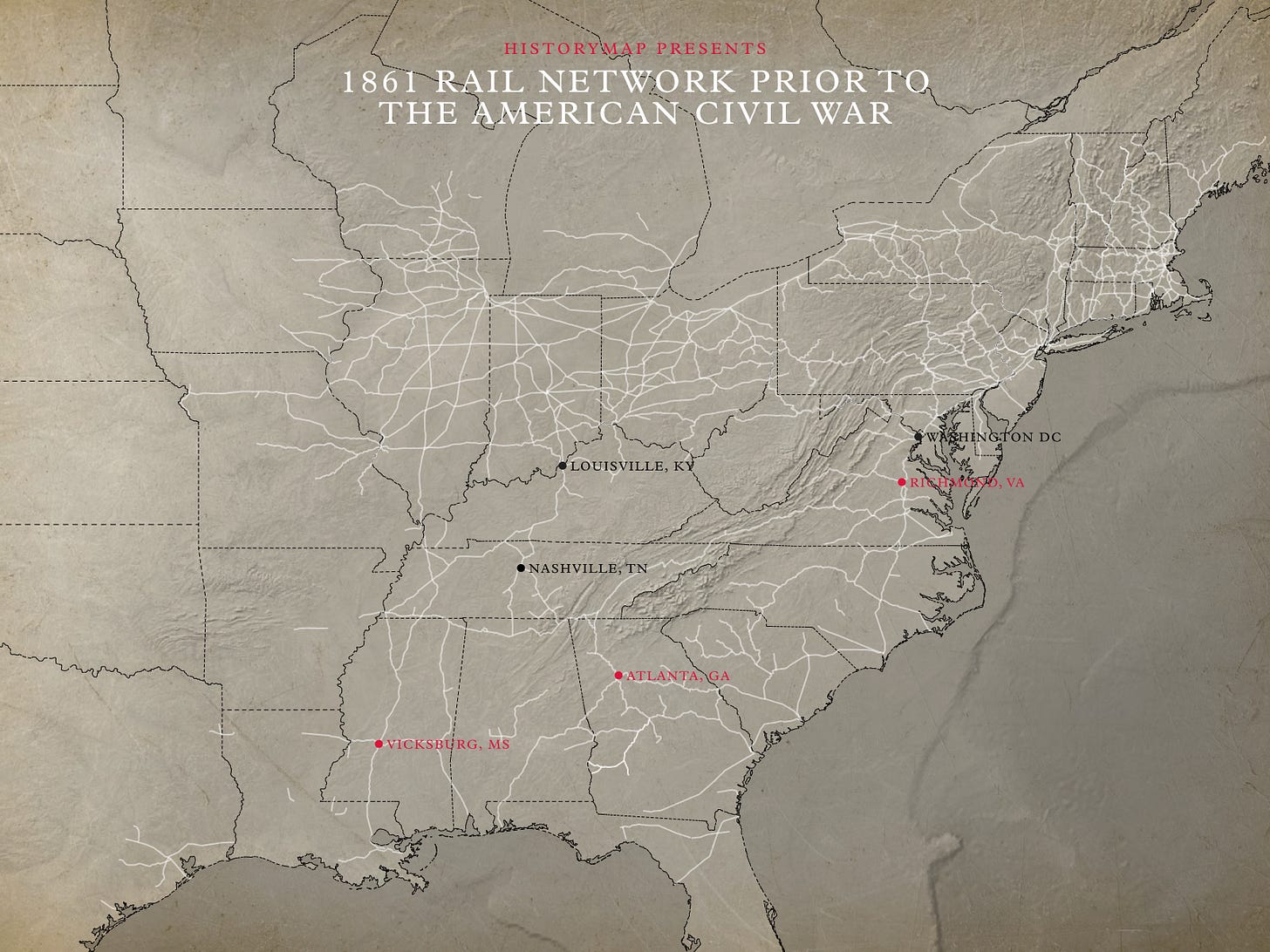

Where does a cycle begin? For American railroads, the Civil War is a good starting point: the conflict demonstrated the value of railroads and was the first major use case for the transformative technology. Better, cheaper, and faster logistics could win wars, and railroads were partially why the North won.

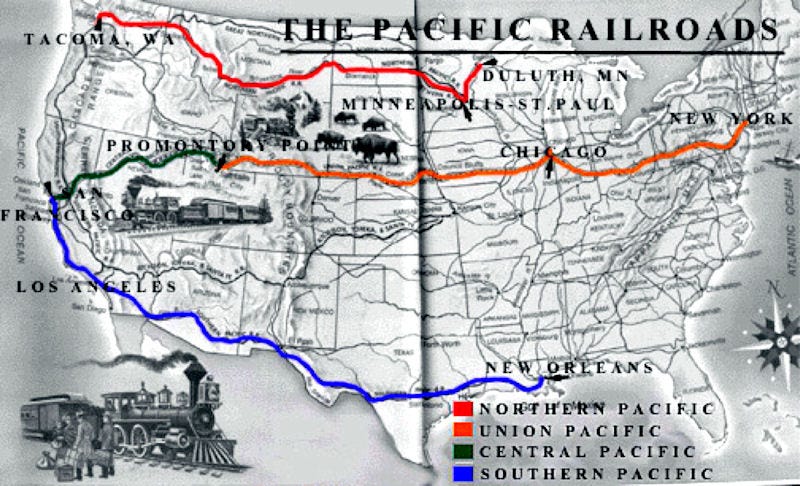

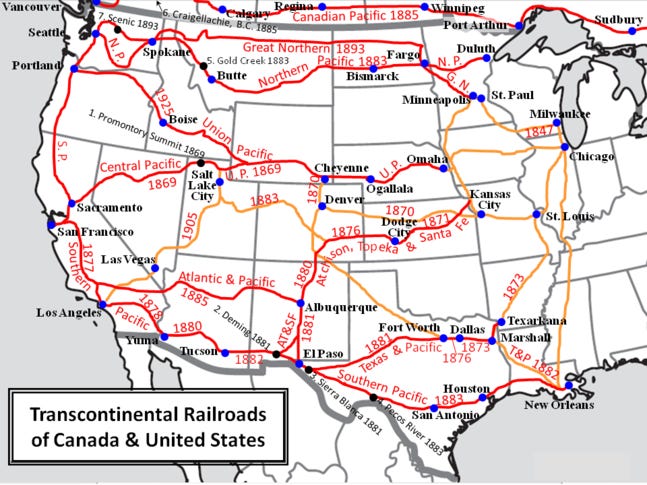

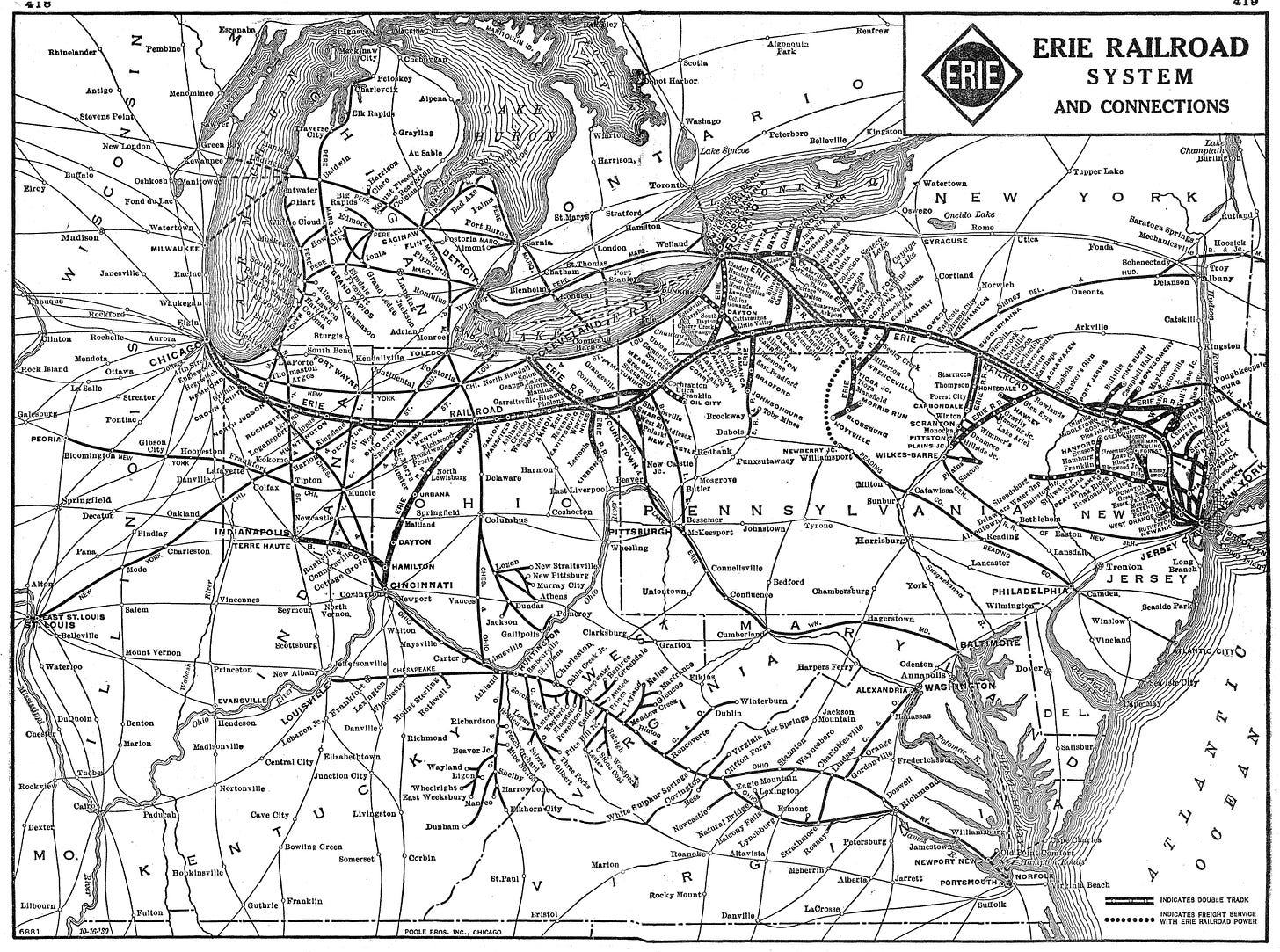

The war was fought over railroads. For example, “Every major Civil War battle east of the Mississippi River took place within twenty miles of a rail line,” and one of the few critical advantages the North had over the South was a dominant standard railroad gauge and a higher quality network. Notice the redundancy of the northern roads compared to the south. And while many factors contributed to the Union victory, this was clearly one of them.

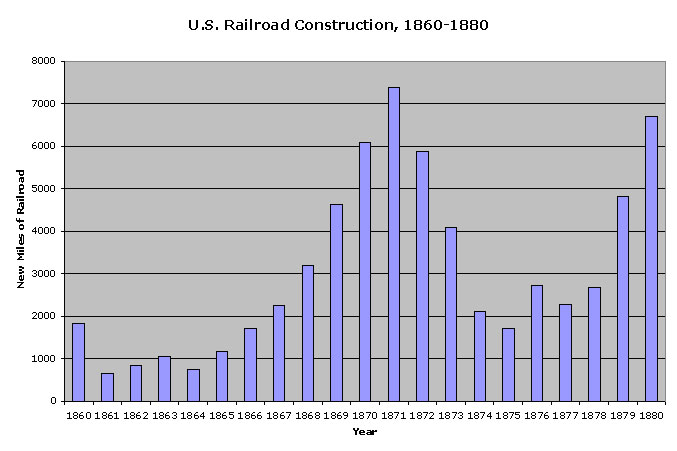

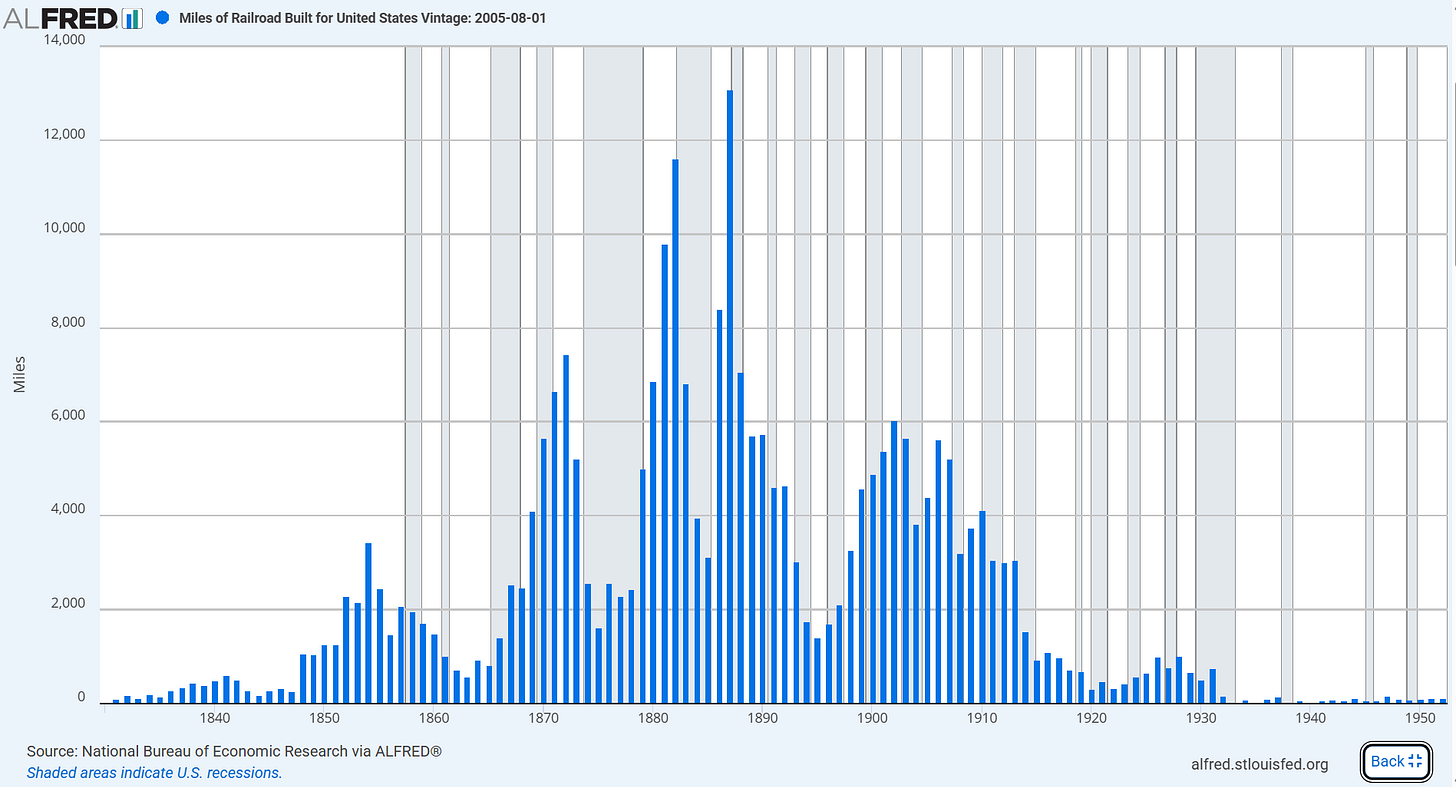

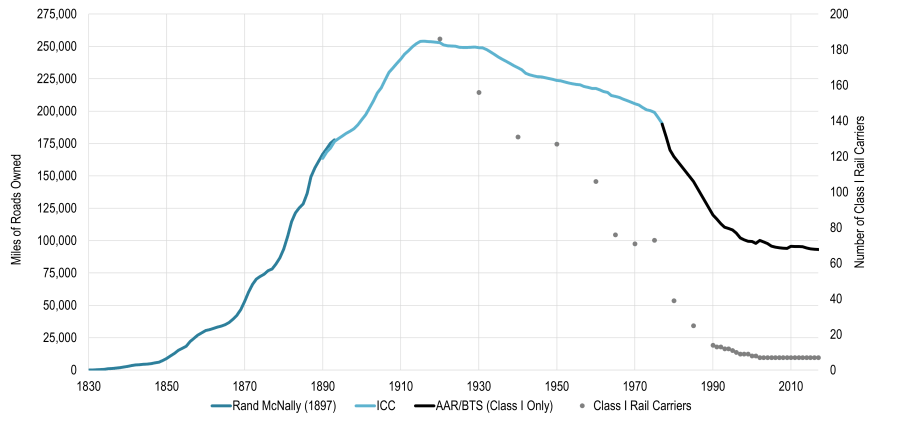

The war demonstrated the value of the railroads, but in peacetime, the railroad industry itself roared to life. At the end of the Civil War (1865), it became clear that technology would shape the American West, and railroad construction increased from ~1000 miles per year to 7000 miles per year within a few years.

But before we go into the dramatic rise (and fall, and rise, and fall) of railroads, I need to discuss one of the core mechanisms that helped finance them in the early days: land grants.

Land Grants and Railroads

The mother of most railroads was land grants. Land grants enabled the financing and construction of the first railroads. The Pacific Railroad Act of 1862, passed during the Civil War, aimed to bind California to the Union before it could contemplate secession and was the first transcontinental railroad endeavor.

Transcontinental railroads were ruinously expensive to build, with costs ranging from $45,000 to $60,000 per mile. In today’s dollars, that’s roughly $2.5 million per mile; for context, the first transcontinental cost about $1.2 billion total. The federal government was cash-strapped, but it had abundant land.

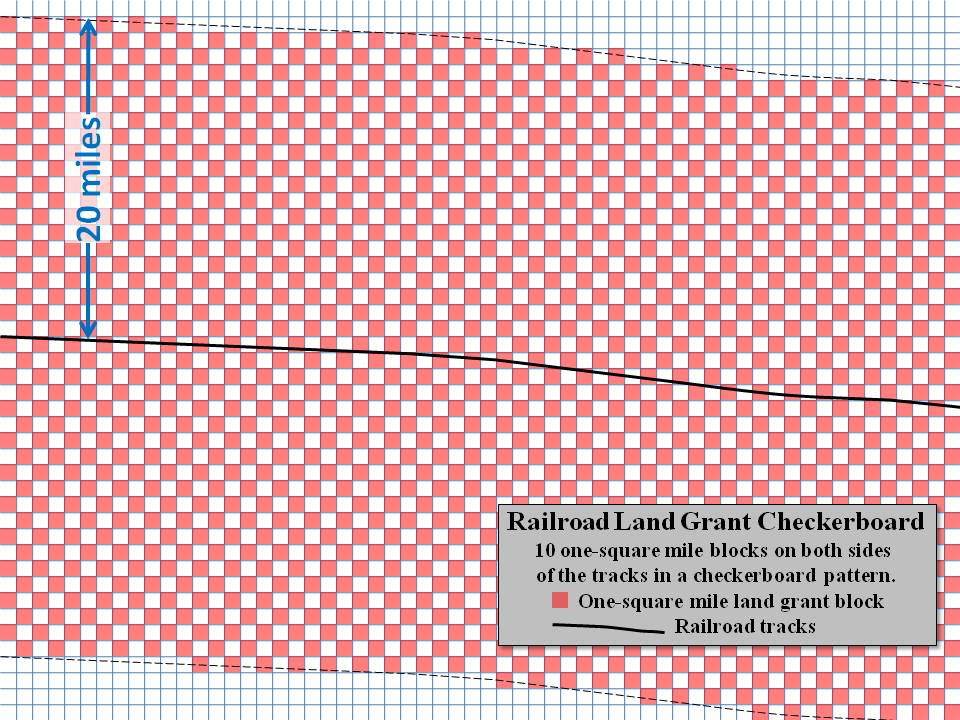

So a clever solution was created: grant land in a 10 to 40 mile corridor around a new railroad to the company itself, and parcel the land 50/50 between the railroad and the government. This would increase the land’s value, as it was in a remote location. The odd sections of the land parcels were conveyed to the railroads, which would then issue securities secured by the land.

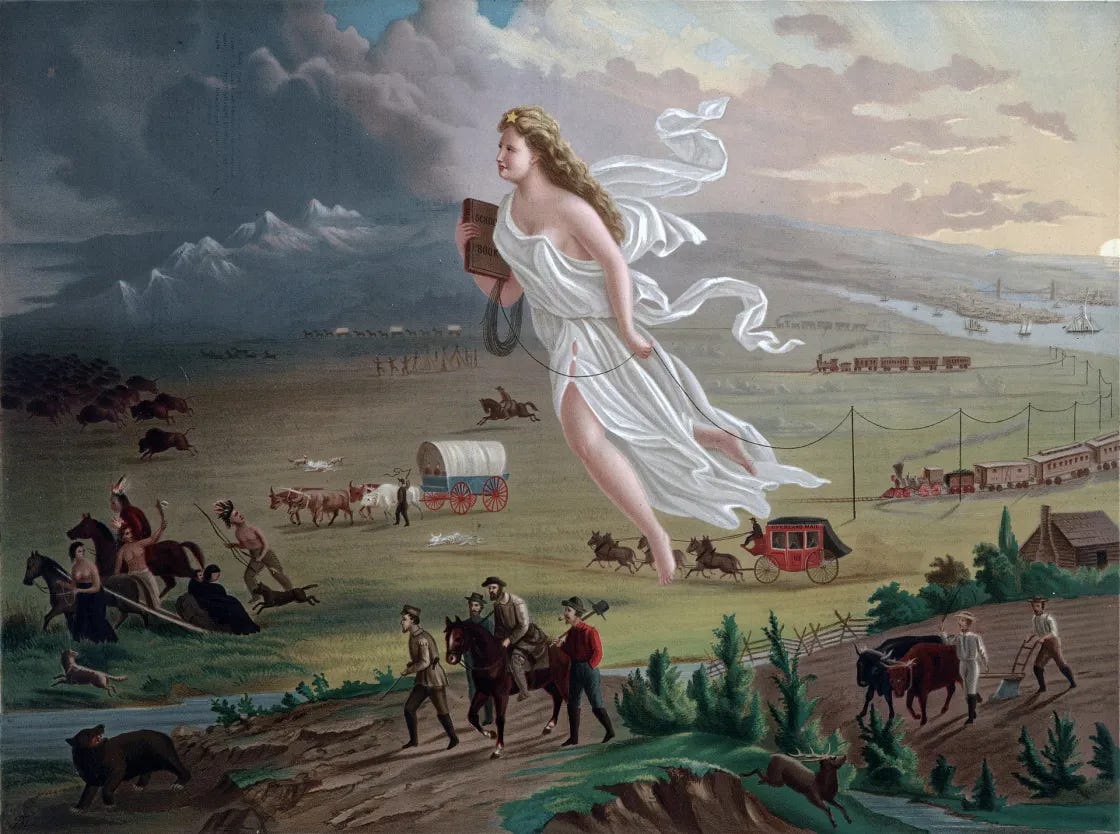

On paper, this was elegant. Public land was sold for $1.25 per acre. Grant half to a railroad, and the resulting settlement would double the value of the government’s retained sections. This was a revenue-neutral transaction for the government, or so the theory went. Another consideration was that Manifest Destiny was viewed as an inevitable defining force of the time, and to expand West was the Zeitgiest itself.

The railroad developer, as the new landowner, had a dual mandate: that of a real estate developer and a transportation company. Sell a farmer's land, then ship his crops when the railroad arrives. The customer base was embedded in the business model and was an essential component of the railroad supply and demand.

But the reality of the land grants was a bit less rosy, according to Robert Henry, the realized price for the government was ~97.2 cents, higher than the carrying value of 12.5-23 cents per acre without transportation access. It created value, but it didn’t pay for the railroads outright.

Railroads, however, monetized their lands at much higher prices, selling them for approximately $2.81-$3.38 per acre. This was still a huge return and was the primary funding mechanism for the first railroads.

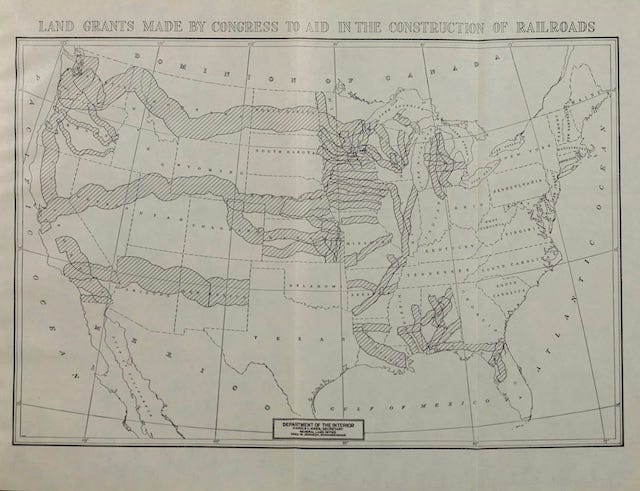

The scale of the land grants was staggering and often exaggerated. Maps like the one below frequently overstated the amount of land granted by a factor of 4x or more and depicted the entire indemnity limits rather than the actual checkerboard. The true figure was roughly 131 million acres, about 10% of the total public domain. For perspective, that’s larger than California and New York combined.

Land was sufficient to prime the pump, and the first major expansion began in 1865 and reached its zenith in 1873, when it collapsed.

The First Great Railroad Buildout Plus Meet the Railroads

Like any mania, excitement went vertical. The post-1865 period was the big bang, with Promontory Point as its focal point.

The network expanded from 35,000 miles at war’s end to 70,000 by 1873, attracting a tidal wave of foreign capital. According to Henry Parris’s “Slow Train to Paradise,” 75% of railroad securities were held by British and Dutch investors seeking growth unavailable in Europe.

The railroad’s biggest product, in many ways, was the act of fundraising itself. Insiders enriched themselves by extracting as much as possible per mile of railroad built. The goal was simple: build a railroad and pay yourself to do so.

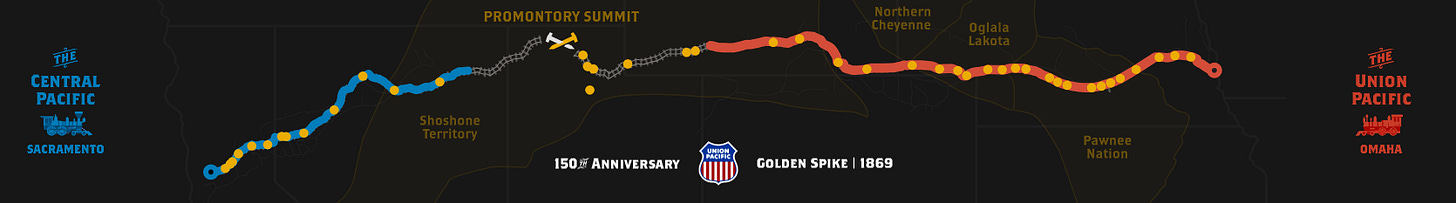

The absurdity of the self-enrichment was visible even at the moment of the Big Bang—Promontory Summit wasn’t chosen for engineering or commercial reasons. Congress insisted on it because the Union Pacific and Central Pacific, racing for land grants, had actually built past each other. Their parallel grades ran side by side for over 200 miles, each company laying track through the same Utah territory to claim more government land. Congress finally intervened and designated Promontory as the meeting point. On May 10, 1869, seven years after the Pacific Railroad Act, the golden spike was driven.

So while I’ve been talking about the great East meets West, let’s actually meet the railroads themselves. It’s important to know the main characters themselves. I will resume the story of the first peak in the railroad buildout after I introduce the key players.

Meet the Railroads and Their Players

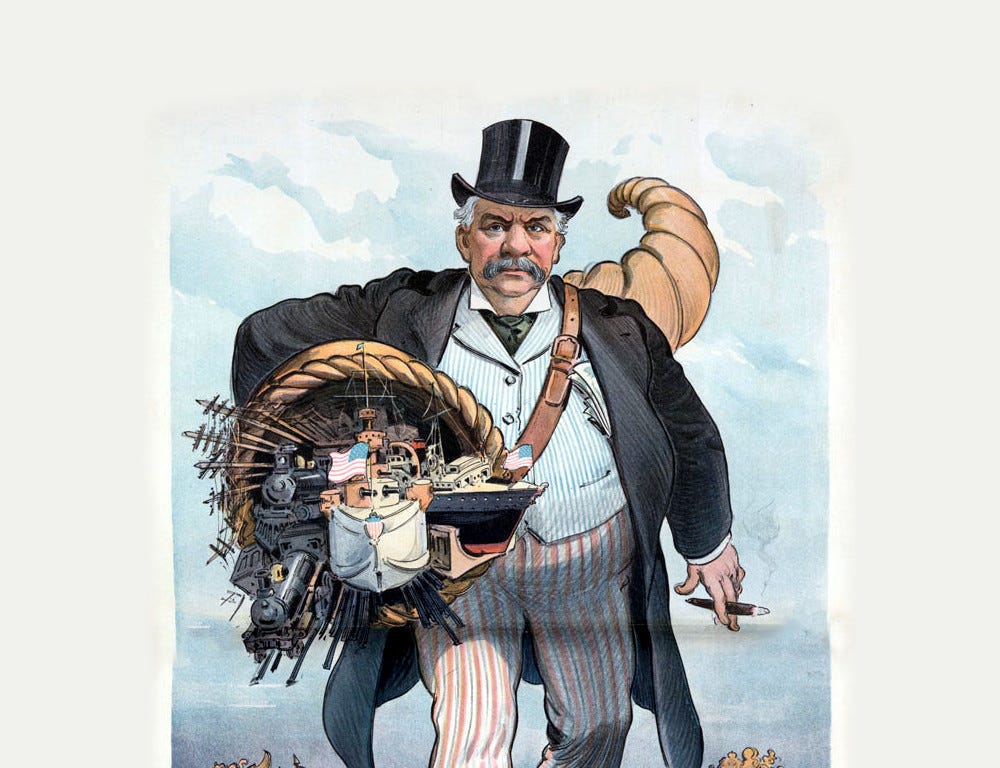

The railroads and the Gilded Age and Robber Barons themselves are impossible to disentangle. The men who built and looted these companies became the era’s defining figures. What follows is a brief guide to the key players and their railroads. So let’s meet the most iconic rail of the era, the Erie.

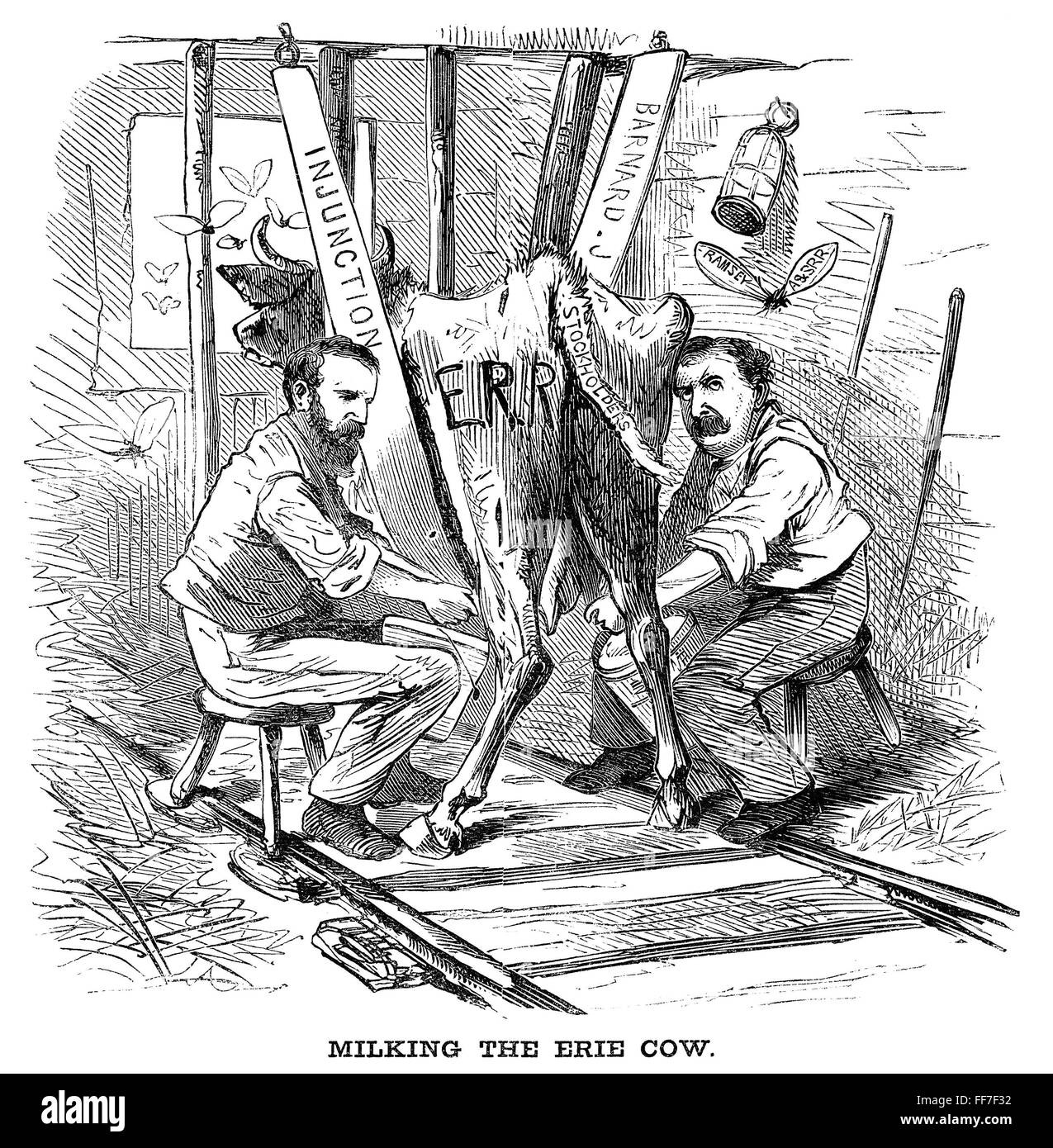

The Erie Railroad: Vanderbilt Jay Gould, Jim Fisk, Daniel Drew (The Speculators)

The Erie connected New York to the Great Lakes and was among the most strategically valuable railroads of its time. Cornelius Vanderbilt, who had built his fortune in steamships before consolidating New York’s railroads, realized that by purchasing it, he could create a larger infrastructure empire. In early 1868, he began buying Erie shares on the open market, assuming the supply was finite.

Supply was infinite. That’s because Jay Gould, Daniel Drew, and Jim Fisk, who controlled the Erie board, set up a printing press in the company’s headquarters and began issuing convertible bonds, which they immediately converted to stock and dumped on the market. For every share Vanderbilt bought, they issued more shares, and this was the first “watering” of stock. After all was said and done, the share count of the Erie increased by over 200%.

Vanderbilt secured an arrest warrant from a friendly (bought) judge. The Erie trio fled across the Hudson to New Jersey, beyond the court’s jurisdiction, with hired guards and, reportedly, cannons defending their hotel. The standoff ended in a negotiated settlement. Vanderbilt lost millions and never acquired the Erie. The Erie was a systematic example of the era, reflecting control over shares and the processes of selling and issuing stock.

Union Pacific: Bankrupt Transcontinental into Shining Success, (Thomas Durant, E.H. Harriman)

The Union Pacific still exists today, but its early history was the most scandalous of any American railroad. Congress chartered it in 1862 to build the eastern leg of the transcontinental, from Council Bluffs, Iowa to Promontory Summit. Thomas Durant, the railroad’s principal promoter, controlled the company but was primarily interested in extracting revenue rather than building efficiently.

His mechanism was the Crédit Mobilier of America. Durant and his allies owned this construction company, which contracted with Union Pacific to build the railroad at wildly inflated prices. Each time a contract with Union Pacific was signed, Credit Mobilier inflated construction costs and booked profits for its owners.

To protect the scheme, Durant distributed Crédit Mobilier shares to congressmen for free, who then controlled the railroad’s land grants and subsidies. The famous “Ox-Bow Incident” captured the incentives perfectly: Durant routed the railroad in a nine-mile loop through Nebraska for no reason other than to claim an extra $144,000 in bonds and land grants.

The scandal broke in 1872 when newspapers revealed the congressional bribery. Eight members of Congress and Vice President Schuyler Colfax were implicated. Union Pacific limped through the Panic of 1873 and into receivership. The railroad Durant built was so shoddy that it could barely operate until much later.

Enter Edward H. Harriman in 1897, after Union Pacific’s second bankruptcy. Harriman was Durant’s opposite: operationally obsessed, financially conservative, focused on the long term. He poured tens of millions into reducing grades, straightening curves, laying heavier rail, and replacing rolling stock. Costs fell. Capacity rose. Union Pacific became one of the best-run railroads in America.

Harriman was still a robber baron. However, he consolidated and operated rather than extracted. His empire would eventually rival Morgan’s. To understand how, we need to meet two more railroads he acquired.

The Central Pacific / Southern Pacific: California’s Railroad (The Big Four, E.H. Harriman)

If Durant represented Eastern corruption, California’s “Big Four” were his Western counterparts: Collis P. Huntington, Leland Stanford, Mark Hopkins, and Charles Crocker. These Sacramento merchants had no railroad experience when they backed Theodore Judah’s vision of a railroad across the Sierra Nevada in 1861. Judah died of yellow fever in 1863, crossing Panama to seek financing in New York. He never saw his railroad completed. The Big Four did, and they profited handsomely from Judah’s work.

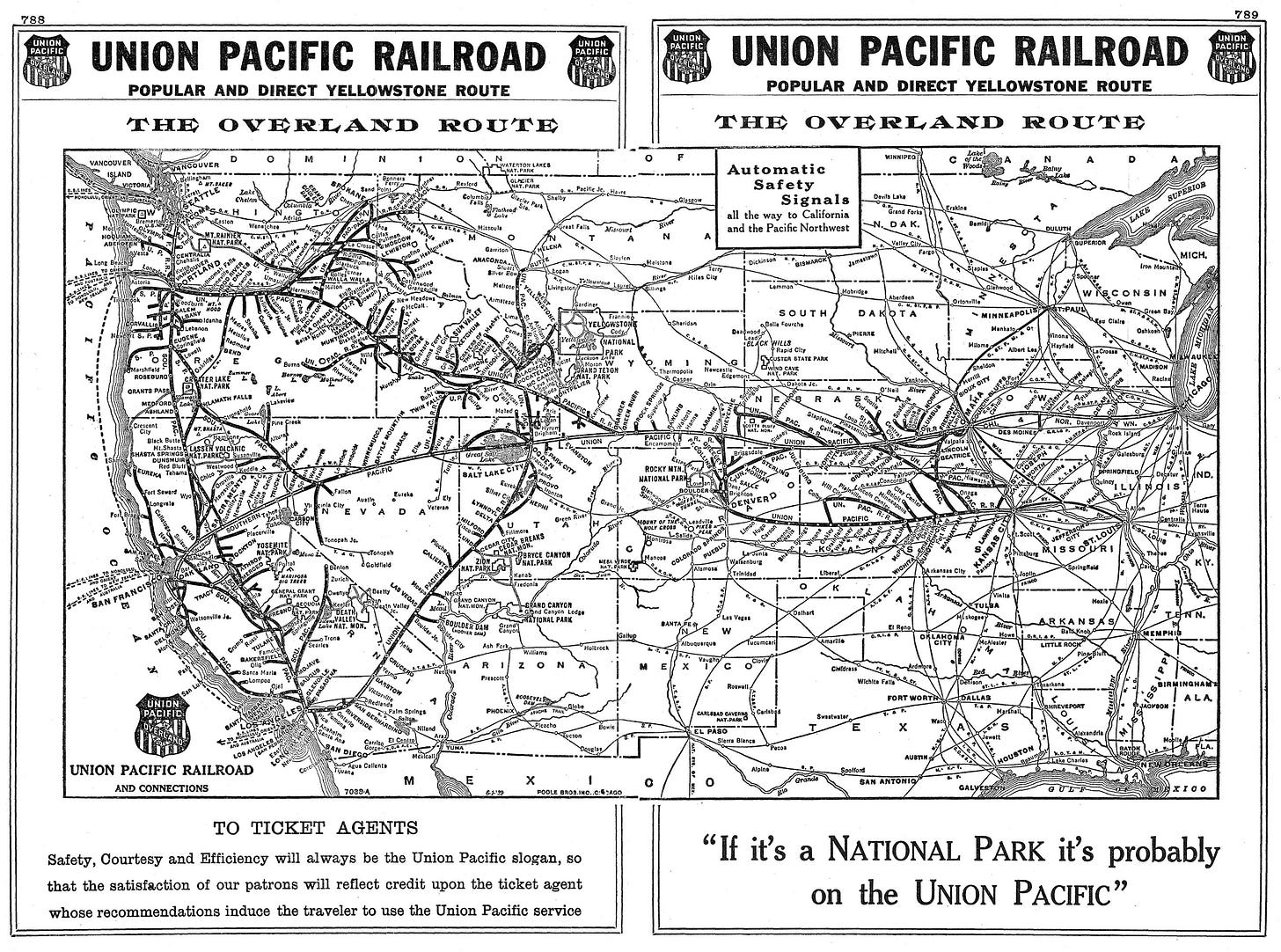

The Central Pacific was primarily built by Chinese laborers, thousands of whom blasted tunnels and laid track through some of the most brutal terrain on the continent. The Big Four, like Durant, created their own construction company to overcharge the railroad. By the 1880s, the Central Pacific had merged into the Southern Pacific, and the combined system controlled nearly every rail mile in California. Farmers and merchants called it “the Octopus” for its stranglehold on rates. Leland Stanford, meanwhile, parlayed his railroad fortune into a governorship, a Senate seat, and a university.

The Southern Pacific eventually stretched from Portland to New Orleans, becoming the dominant railroad of the West. Harriman acquired control in 1901 and, as with Union Pacific, invested heavily in rehabilitation. For a brief period, he controlled both railroads, creating the most powerful transportation empire America had seen. The Supreme Court forced the combination apart in 1913, but by then Harriman was dead.

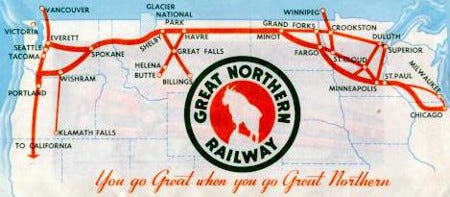

The Great Northern (James Hill)

James J. Hill was the anti-everything. Hill built without land grants and managed his empire differently compared to the other majors. Where they watered stock, Hill reinvested profits in the railroad. Where they extracted, he developed. The Canadian-born “Empire Builder” created the only transcontinental railroad that never went bankrupt, and he did it by being smarter, cheaper, and more patient than everyone else.

Hill started with the bankrupt St. Paul & Pacific in 1878, a distressed Minnesota railroad that more astute investors had dismissed. He rebuilt it methodically, extending west only when the existing line was profitable, selling farmland to settlers who would then ship crops on his trains. By 1889, he’d renamed it the Great Northern Railway and set his sights on Puget Sound.

His secret weapon was Marias Pass. Native American stories spoke of a low crossing through the Rockies in northern Montana, but no surveyor had found it. Hill hired John F. Stevens, who located the pass in December 1889, at an elevation of 5,215 feet, versus the Northern Pacific’s much higher crossing to the south. Hill’s route had lower grades, fewer curves, and lower operating costs. When the Great Northern reached Seattle in 1893, it was the most efficiently built transcontinental in America.

Hill’s philosophy was that a railroad’s prosperity depended on the prosperity of the territory it served. He distributed purebred bulls to farmers, promoted scientific agriculture, recruited immigrants from Scandinavia, and developed infrastructure rather than simply extracting resources. When the Panic of 1893 bankrupted the Northern Pacific, the Santa Fe, and the Union Pacific, the Great Northern continued to operate profitably.

Hill eventually gained control of the Northern Pacific and the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy, creating a northwestern empire that rivaled Harriman’s. The two titans clashed spectacularly in 1901 when Harriman attempted to seize the Northern Pacific through a stock corner, nearly crashing Wall Street before J.P. Morgan brokered a truce. More on that later.

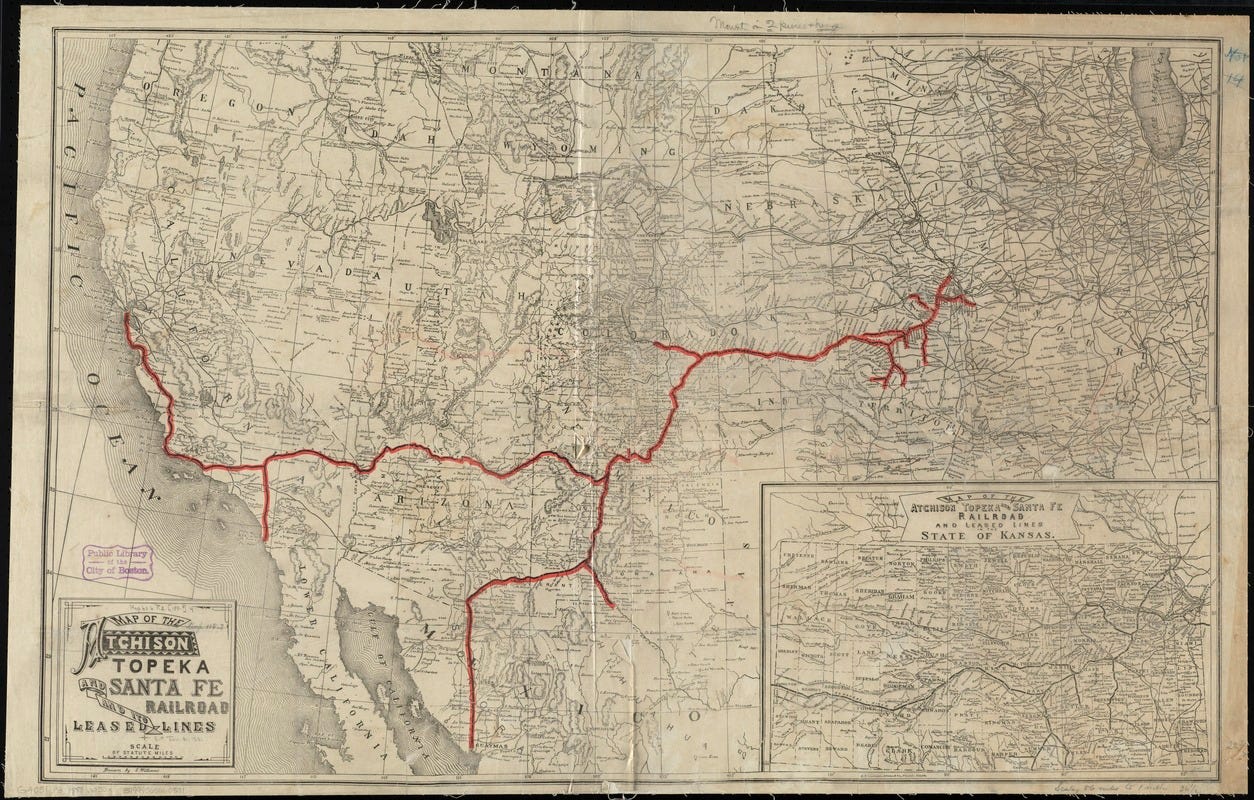

The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe (Cyrus Holliday, William Barstow Strong, Fred Harvey)

The Santa Fe was built on audacity and marketing genius. Cyrus K. Holliday, a Topeka lawyer, drafted the railroad’s charter in a Kansas hotel room in 1859, dreaming of a line that would follow the old Santa Fe Trail to the Pacific.

The railroad grew through cattle towns: Newton, Wichita, Dodge City. It became the preferred shipper for Texas cattle drives heading to Kansas railheads. But the true expansion came under William Barstow Strong in the 1880s. Strong raced the Denver & Rio Grande for control of Raton Pass, the key gateway into New Mexico. He sent construction crews to occupy the pass at dawn, hours before his rivals arrived. The Santa Fe reached Los Angeles by 1887 and Chicago by 1888, becoming the only transcontinental connecting the Midwest directly to Southern California.

What made the Santa Fe legendary, though, was Fred Harvey. Beginning in 1876, Harvey built a chain of restaurants, hotels, and dining cars along the route, transforming western travel from an ordeal to an experience. The Harvey Houses served high-quality food on real china with professional service, a revolutionary innovation for the frontier. The “Harvey Girls,” young women recruited from the East to work as waitresses, became a civilizing force in railroad towns and the subject of a 1946 MGM musical. The Santa Fe focused on the customer experience.

Okay, after the long detour of players, let’s get back to the first build and bust cycle. As you can tell, we have many busts to discuss.

The Build and Bust (1873)

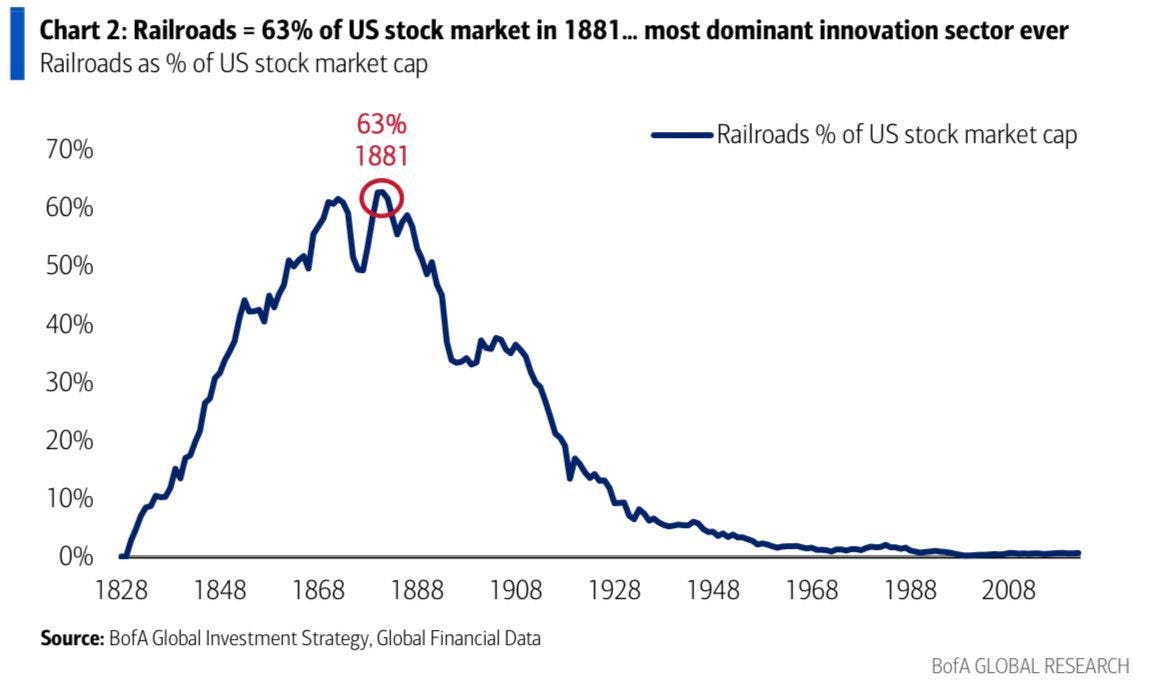

Throughout the original buildout, railroad securities were the hottest asset class in the world. European capital poured into America to finance the new network.

However, the land grant model created a perverse incentive: build first, address traffic later. For many railroads, the goal was to lay track and claim land. Whether the route made economic sense was secondary. The result was massive overcapacity and dozens of duplicate routes competing for the same freight.

The breaking point for this cycle came from capital markets, and not the technology. In May 1873, the Vienna Stock Exchange collapsed after Austria-Hungary demonetized silver, triggering bank failures across Europe. Investors who had financed American railroads suddenly needed liquidity. They sold shares for liquidity, and selling pressure mounted through the summer. The Credit Mobilier scandal also ended all land grants after the fraudulent allegations.

In September of 1873, Jay Cooke & Company declared bankruptcy. Cooke had financed the Union during the Civil War and emerged as America’s most prestigious banker. After the war, he bet everything on the Northern Pacific, attempting to build a second transcontinental without the subsidies that Union Pacific and Central Pacific had enjoyed. But he ran out of money as bond sales stalled. The bank collapsed on September 18.

The New York Stock Exchange closed for ten days. The Panic of 1873 was called the “Great Depression” until the 1930s claimed the title. Railroad construction fell 78% between 1872 and 1875. Eighteen thousand businesses failed. Unemployment reached 14% nationally and 25% in New York City.

Railroads suffered the worst of all. Between 1873 and 1879, half of all railroad bonds defaulted. More than a billion dollars (~134 billion dollars today) in debt went bad in 1874 alone. Union Pacific entered receivership. Northern Pacific went formally bankrupt, its line stranded incomplete in Montana. More minor roads vanished.

But the track stayed in the ground. The rolling stock continued to roll, slower now, less frantic. And when the economy finally recovered, all that infrastructure, built with European money, now wiped out, was available at fire-sale prices. The contraction lasted 65 months, the longest in American history to that point. Workers bore the brunt: wages collapsed, and the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 became one of the most violent labor actions the country had seen. The men who bought bankrupt railroads in 1878 built some of the era’s greatest fortunes.

The Second Build: From Bust to New Mania (1879-1893)

Here’s the thing about capital-intensive industries: they are cyclical. The 1873 crash was the warm-up for the second larger cycle. The expansion from 1879 to the zenith in 1893 is what we now call the Gilded Age, and the scale dwarfed that of earlier periods.

By 1882, more track was laid in a single year than had existed in the entire country in 1850. This was the core period of rapid railroad expansion, during which railroad mileage more than doubled, from 93,000 miles to 164,000 miles. At the end of this period, the United States had the most railroad track laid in the world, and it still holds that title to this day. And this time it wasn’t land grants, but Wall Street that led the way.

The Invention of American Finance: Financing Railroads

In 1871, after the Credit Mobilier scandal, land grants from the government rolled to a halt. So how did railroads accelerate despite the end of “free land”? The answer was Wall Street. And to go deeper, you have to understand that Wall Street as we know it didn’t exist before railroads. The railroads created such a funding need that they gave rise to Wall Street.

Before the advent of railroads, Wall Street barely functioned as a capital market. In 1830, there were a few dozen securities trading, mostly bank shares and state bonds. Daily volume measured in hundreds of shares. The modern stock market didn’t exist because there was nothing large enough to require it.

A textile mill at the time costs $100,000. Wealthy individuals, retained earnings, or short-term bank loans could cover that. Railroads cost millions. A hundred miles of track between two cities ran $3-5 million. A trunk line cost $20-30 million. A transcontinental cost more than the annual federal budget.

No single bank had that kind of capital. Railroads required a new solution: raising capital from thousands of investors who had never met one another, had never seen the property, and would never manage the company. The concept of modern shareholders, the capital stack, and how to finance large projects emerged in response to the funding needs of railroads.

Common stock existed before railroads, but was rarely traded. Railroad shares were the first stocks to be widely traded by a broader group of people rather than a small group of owners. So when you see the claim that “railroads were 60%+ of the market,” it is backwards. Railroads essentially gave rise to capital stock markets because of the substantial capital requirements to build them, so of course, the concentration in the 1880s was massive.

Meanwhile, corporate bonds as a mass-market security were a railroad innovation. The concept of a capital stack was developed to finance railroad construction. Investment banking as a profession emerged to sell railroad securities. The great banking houses - namely, J.P. Morgan, Kuhn Loeb, Jay Cooke, Drexel- all built their fortunes on railroads.

The ticker tape itself was designed primarily to transmit railroad stock prices! Financial journalism was invented to cover railroads. The Wall Street Journal was founded in 1889 primarily as a railroad sheet. Moody's, Standard & Poor's, and many modern financial companies were established to assess railroads.

Accounting standards were introduced to standardize the preparation of often fabricated annual reports and financial statements. Depreciation as a concept was introduced to account for the long lives of railroads. All of finance was invented as a downstream industry to support the railroads, and that itself is an incredible story. The 1880s were a railroad-dominated stock market, and bonds actually accounted for an even higher share of total issuance than stocks. The entire economy was a railroad.

And the birth of the 1880s Wall Street machine was built with a single purpose: to finance the second, much larger machine of railroads. And Wall Street’s strength had grown powerful to create something genuinely unprecedented, and that is the second great boom.

The First Great Wall Street Boom

The 1880s saw the full strength of financial engineering bent on building more railroads. The first generation of promoters, such as Durant, had used construction companies to extract value; the second group of titans realized they could extract more value from railroad securities and expectations on the railroads. Railroads issued bonds against future traffic, against branch lines not yet built, against connections to towns that didn’t exist except for on promotional maps. These were literal roads to nowhere financed by paper securities.

The entire railroad capitalization (stocks plus bonds) grew from $4.6 billion in 1876 to $10.6 billion in 1890. The incredible thing is that most of this was not actual infrastructure but financial products. One railroad historian estimated that by 1890, 40% of railroad capitalization represented “water”, or securities issued in excess of any investment in roadbed, rails, or rolling stock.

And this incredible financial machine lured back European investors en masse. Despite being burnt in 1873, foreign holdings surged to $3 billion, or a quarter of all outstanding railroad capital in America. And unlike the land-grant era, in which the government provided at least some discipline through the granting process, Wall Street financed anyone with a sufficiently compelling story and sufficient demand. If investors purchased the bonds, they would be issued. If you could sell a story and bonds, you too could potentially build a railroad, regardless of whether the railroad made any economic sense at all.

The Transcontinental Race (Again)

Despite the previous transcontinental going into bankruptcy, the urge to build another one roared again to life. In 1880, there was effectively one transcontinental, but by 1893, there were five transcontinentals.

The Northern Pacific, left incomplete and bankrupt in Montana, reorganized and finished in 1883 under Henry Villard. Henry Villard was an incredible promoter, and after completing the road promptly ran out of money. Northern Pacific would struggle for another decade.

The Sante Fe, under William Barstow Strong, reached Los Angeles in 1887. Strong acquired his way eastward, reaching Chicago in 1888. The Santa Fe connected the Great Lakes to the Pacific.

James Hill’s Great Northern reached Seattle in 1893, and was the only transcontinental built without land grants and without meaningful leverage. More on Hill later.

The Denver & Rio Grande, the Missouri Pacific and Texas & Pacific extended towards the Southwest. Regional systems such as the Chicago & Northwestern, the Burlington, etc, all expanded to prevent being outflanked by competitors.

But the problem was that Wall Street's financing capacity had completely outstripped economic reality, and the system could raise more capital than the economy could productively absorb. Five transcontinental railroads existed when demand could barely sustain two, and many railroads built parallel routes competing for the same shipments. The railroads massively overbuilt for a future that would never arrive. Enter the rate wars.

The Rate War Spiral

It’s simple, if there is too much supply chasing too little demand, prices collapse. And this is where the rate wars began. Rate cuts were vicious and destructive cycles of competitive price-cutting that drove rates often below operating costs. The Chicago to New York freight rate fell from 35 cents per hundred pounds in 1873 to under 20 cents by 1886. Passenger rates fell from over $100 a ticket to as low as $1 during the most intense fare wars of 1886-1887.

Railroads formed cartels to fix prices on routes. But the cartels collapsed, the temptation to cheat was irresistible when you had high fixed costs and empty variable pricing (cars) to fill. Railroads even lobbied for regulation, and the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887 proved toothless and not enough to turn around the price war.

Nothing could stem the overcapacity. No financial arrangements could fix the reality that there were too many railroads chasing too few customers.

Jay Gould really embodied this era. After his Erie saga, he moved west and assembled 16,000 miles of railroad. Similar to the Erie, he specialized in speculation and financial manipulation. He acquired a struggling railroad, issued bonds to raise cash, triggered rate wars to damage competitors, and often profited more by shorting competitors’ securities simultaneously. Jay Gould died in 1892, one year before the Panic of 1893.

The Panic of 1893

The 1893 collapse destabilized the system and was among the first global crises of its time. It’s hard to start in one place, but let’s begin with Argentine railroads.

In 1890, Argentina had the highest per-capita foreign debt in the world, and when a failed coup rattled Buenos Aires that summer, creditors panicked. Baring Brothers, one of Britain’s oldest banks, found itself holding the bag. In November of 1890, it nearly collapsed, but survived after the Bank of England organized a rescue.

British investors started the risk-off trade, and Australia was next. Melbourne had a speculative railroad mania in the 1880s, and during its collapse in 1893, real GDP fell 17%. This contagion spread worldwide: British investors burned in Argentina, British investors in Australia began to sell American securities, and gold began flowing out of the United States. Enter McKinley and the Silver Purchase Act.

The McKinley Tariff and the Silver Problem

In 1890, Congress passed two pieces of legislation that, in combination, were a catastrophe. First McKinley Tariffs raised average duties to nearly 50% to protect the domestic industry. This reduced imports, thereby limiting foreigners' ability to purchase American products and, significantly, to own American securities. International trade contracted, and gold continued flowing out of America.

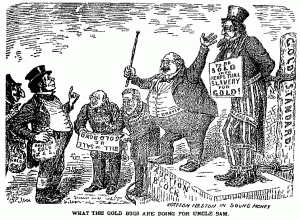

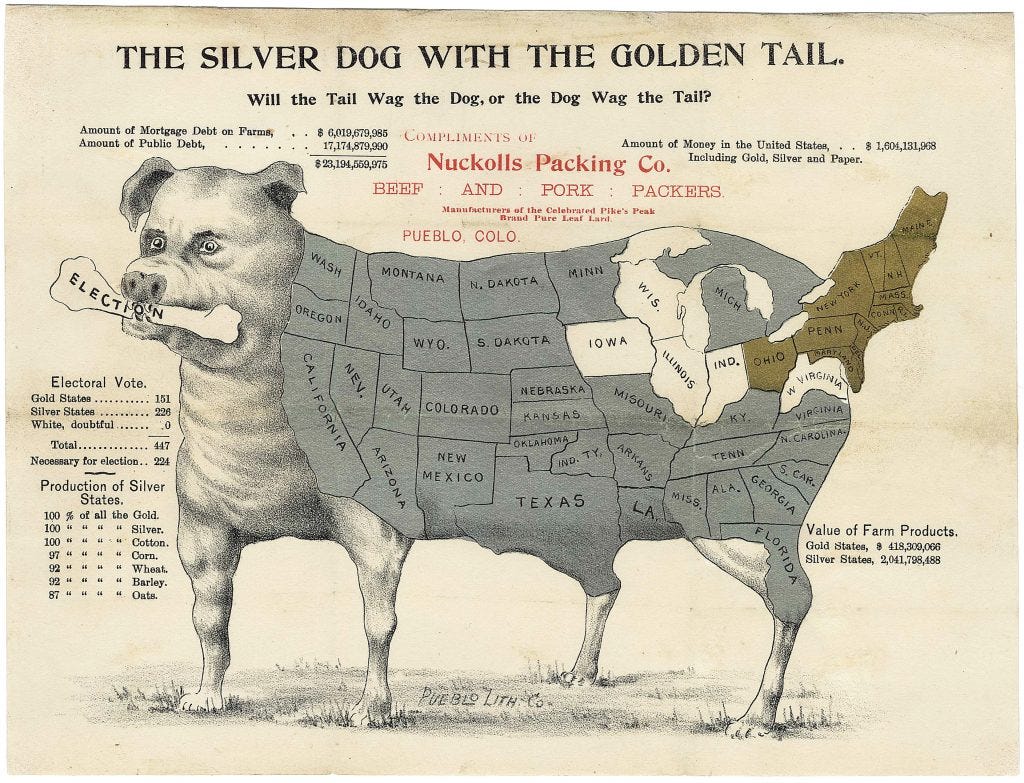

Second, the Sherman Silver Purchase Act created a second type of gold drain. Western farmers (and populists) demanded “free silver” or the ability to swap silver for gold at a fixed ratio, creating inflation that would help ease debts and inflate crop prices. Now, the government didn’t love this, so the Sherman Act was a compromise; it required the Treasury to purchase 4.5 million ounces of silver monthly, paid with notes redeemable in either gold or silver.

The problem is that silver is easier to obtain than gold, and silver was overvalued relative to the gold peg. Holders of Treasury notes redeemed them exclusively in gold, not silver. By issuing more notes that would be withdrawn this accelerated the gold withdrawals. Reserves at the United States Treasury fell from $190 million to the $100 million minimum required by law. Foreign observers doubted whether the gold standard would hold in the United States, which in turn precipitated a further run on Treasury securities and increased pressure on gold and the gold standard.

By early 1893, the treasury’s gold reserve was dwindling. This is all to set the stage for the eventual panic.

Bank Failures and Dominoes Fall

The Philadelphia & Reading Railroad declared bankruptcy on February 20, 1893, 10 days before Grover Cleveland’s inauguration. The Reading tried to corner coal, and while the company failed, the market mostly absorbed the shock.

In May, the National Cordage Company (a rope trust) collapsed, triggering a broader stock market fall. Credit markets froze, banks called loans, and then railroads, with massive debt balances backed by minimal earnings, began to fail. This was a violent and aggressive move, much like 1873, but on a larger scale.

By the end of 1893, 74 railroads entered receivership, representing 30,000 miles of track and $1.8 billion in capital. By 1897, 192 railroads failed, representing 1/4th of all railroad track in the country. This wasn’t just small speculative companies. The Union Pacific failed in October 1893 (again lol), the Northern Pacific failed the same month. The Santa Fe entered receviership in December, and the Erie failed again (for the fourth time)—the Reading Failed, etc, etc. You get the point, but this contraction wasn’t quite as bad as 1873, just in absolute dollars, much larger.

Only Hill’s Great Northern (with minimal leverage) survived intact.

President Cleveland, convinced that the Sherman Silver Purchase Act was killing confidence in the dollar, called a special session and repealed the act in late 1893. Gold continued to flood out, and in 1895, Cleveland had to turn to J.P. Morgan to organize a private syndicate to lend the Treasury $65 million in gold to prevent the US from leaving the gold standard entirely. The federal government needed a bailout from a private banker.

Silver Radicalized, and the Cross of Gold

Ironically, the opposition (farmers) were enraged even further. The deflation crushed miners and farmers, and Cleveland’s actions meant that they were left out in the cold. By 1896, silver supporters had seized control of the Democratic Party. And at the Chicago national convention, William Jennings Bryan’s “Cross of Gold” address electrified delegates. He won the democratic ticket.

“You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns. You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.”

Bryan's Democratic nomination led him to ally with the populist party, which consisted of western farmers, silver miners, and urban workers, against the powerful “money” interests of the East. The 1896 election was a referendum on the gold standard and, to some extent, on the Gilded Age itself. Shares were mixed in this entire period.

But Bryan lost, William McKinley carried the day, and was backed heavily by private interests. McKinley’s strategy of sound money and high tariffs prevailed decisively, and the Gold Standard Act of 1900 committed the United States to the gold standard. But let’s bring this all the way back to Railroads, because this crisis broke the financial system that supported railroads.

The wild speculative capitalism of the 1880s, with European bondholders financing American speculation with zero oversight, was done. Enter the era of concentrated banker control, also known as “Morganization”.

The Morgan Reorganizations

After saving the government, John Pierpont Morgan stepped into the wreckage with a checkbook in hand.

He had a standard template. Foreclose on the existing capital structure, create a new company with less debt, and raise capital for the new owners to reorganize the company. Morgan then installed Morgan-selected management with Morgan-selected partners on the board. These boards often had interlocking ownership structures, including among competitors.

The promise was stability. If you reorganized your railroad with Morgan, you wouldn’t have a rate war with other Morgan railroads. The banker became a soft-power regulator of an industry that couldn’t control itself through price cuts.

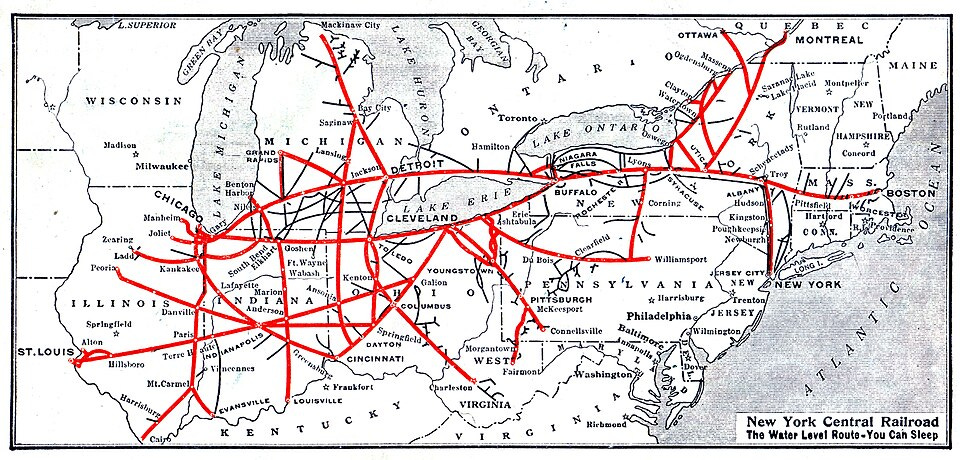

Between 1893 and 1898, Morgan reorganized the Southern Railway, the Erie, the Reading, and the Northern Pacific. Other banks followed suit, with Kuhn Loeb reorganizing the Union Specific, Speyer, and the B&O. By the end of the decade, Wall Street had restructured and controlled most major American railroads.

The reorganizations worked, and with improved capital structures and diminished pricing pressure, railroads emerged stronger from the wreckage. They did, however, also leave much more concentrated. The same industry that had fueled the excess also reigned it in, and now Morgan owned the railroads.

The Northern Pacific Corner (1901)

Now for the final story before we wrap up. I would like to discuss the Northern Pacific Corner. Harriman emerged during this period by purchasing the bankrupt Union Pacific and quickly became one of the wealthiest men alive. After reinvesting in the railroad and then acquiring other competitors, he created the first conglomerate system.

Meanwhile, James Hill had been building the entire time prudently. Hill went after the Burlington to connect Chicago and Seattle, and at the time Harriman watched in alarm. This was a real competition for Harriman’s system. Harriman sought a stake in the Burlington, but Hill refused; instead, Harriman pursued the parent company.

Harriman quietly began buying Northern Pacific stock. By May 6th he thought he had enough shares to buy the entire company, and lastly wanted to buy preferred shares to wrestle control. Harriman’s banker (Jacob Schiff), however, didn’t execute the order (talk about all-time poor order execution), and by Monday, the corner was public news. Hill had learned of the news and phoned Morgan, who was in Europe, and cabled back to buy 150,000 shares of Northern Pacific common at any price.

This was a time before retained earnings, so most common shares traded at par, and appreciation was reflected in dividend payments rather than in earnings. Northern Pacific shares shot up from $100 in April to $147.50 on May 6th. On May 7th, $180; on May 8th, $280; and on May 9th, Northern Pacific reached $1,000 per share.

Short sellers bet against the price rise, creating the most epic short squeeze of the time. And since the titans of industry were buying at any price for control, they drove share prices higher. Harriman and Hill purchased more stock than actually outstanding, as shorts sold shares they didn’t own or could not deliver. Now the problem was to cover their positions shorts had to sell everything else. Stocks fell 20-50% in a single day as the liquidity black hole caused the Panic of 1901. All for control over a railroad and the resulting short squeeze.

Morgan and Schiff came to a truce. The shorts were permitted to settle their positions at $150 rather than face ruin, and the battle for control was inconclusive. So instead, a new holding company was created, the Northern Securities Company, which would own both the Northern Pacific and the Great Northern. Hill and Morgan were in control, but Harriman had a meaningful stake. The railroad wars (and the last big consolidation wave) were over.

Anti-Trust and the Long Decline

Now, given this is an economic history, I have to briefly touch on the decline. Roosevelt hated the railroad wars, and the attorney general filed suit under the Sherman Antitrust act. Railroads at the time were confident, as the administration before was extremely pro-business. But in 1904, the Supreme Court ruled 5-4 that Northern Securities violated the Sherman Act and must be dissolved.

Shares were distributed, and Harriman and Hill cooperated, but this would be near the zenith of railroads anyway. Harriman died in 1909, and Hill died in 1916; although they had incredibly organized the railroad markets, the end was beginning.

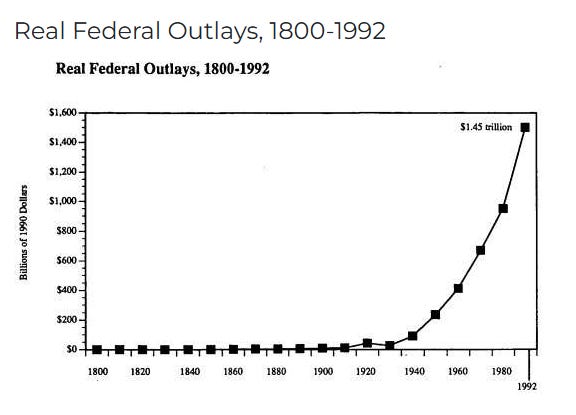

The peak in total miles of railroads was in 1910, with about 240,000 miles of track and 1.7 million workers. They were the largest enterprises the world had yet seen, consuming vast amounts of capital and employing ~2% of the United States population.

But at their zenith, their disruption was in the wings. Automobiles started to compete with passenger traffic, and trucks began stealing short-haul freight. The Panama Canal diverted transcontinental shipping, lowering prices, and the Interstate Commerce Commission began regulating rates in a meaningful way.

World War I was the catalyst that pushed the system over, and in December of 1917, as railroads failed to coordinate logistics, the federal government nationalized the whole industry. For 26 months, the railroads were operated by a single entity, and when they remerged, they would never be quite as dominant as they once were. Governments regulated rates, and a fair return on investment was established.

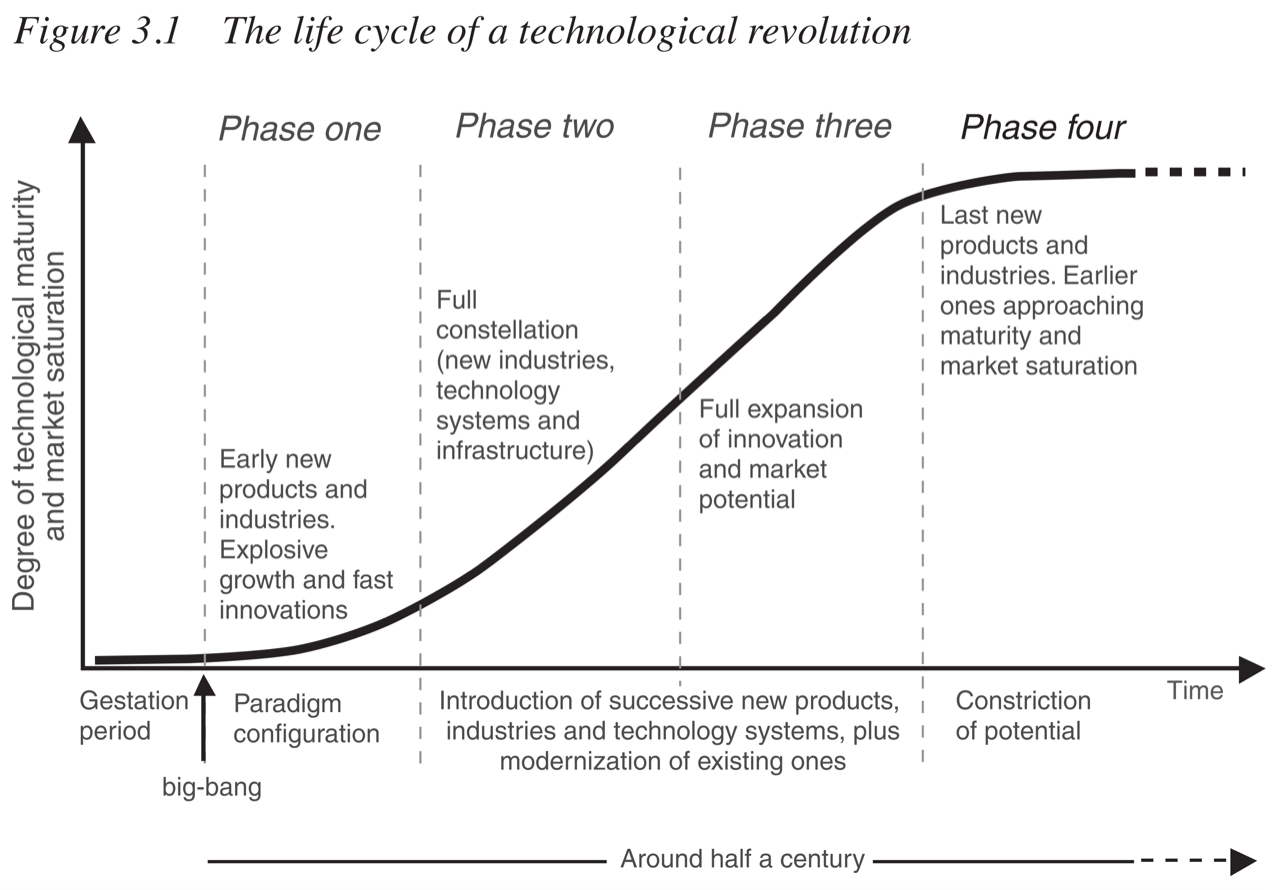

Total mileage peaked in 1916 and subsequently declined. The Penn Central failure in 1970 was the largest corporate bankruptcy in American history to that point. Today, railroads have roughly ~140,000 miles of track, down 40% from the peak. The whole cycle of innovation, speculation, overbuild, crash, consolidation, regulation, and decline had taken approximately 60 years.

The Capital Cycle Lessons, Then and Now

So now that we’ve done the whirlwind tour of railroads, what the hell does this have to do with semiconductors and AI? Well, of course, an infrastructure buildout! I think as time has gone on and as the benefits have become “clearer”, the infrastructure buildout that I am starting to resonate more with is the railroad bubble/capital cycle. Let’s discuss why, and then also some broader overlaps between the AI buildout today and railroads.

As a sidebar, I will not cover everything. I wrote some about this here, and will not try to duplicate work.

I will try to focus on how the railroad cycle is “different” more so than repeating previous lessons.

Government Involvement

First, I think we are approaching the aggregate ~1 trillion in investment that the telecom bubble had in real terms from 1996 to 2000. It seems likely that the aggregate capex will far outpace the telecom bubble in real terms, and that makes me look back further for analogies. I think another significant difference between the Telecom buildout and the Railroad buildout is that the government was highly supportive and integral to the whole buildout.

While you can argue that the telecom deregulation bill signed by Bill Clinton helped spur the buildout, I think changing the industry structure for favorability versus actively pouring fuel on the fire, à la land grants or launching the “Manhattan project for AI,” is fundamentally different. The administration and corporate interests are way more aligned in this buildout, and in my opinion, it is a closer overlap with the railroad cycle than the telecom cycle.

Demand Chases Supply, Price Cuts Follow

I think the other takeaway here is that price is going to be the ultimate driver of demand, and in this case, price cuts are the most important metric to follow. We should expect some price erosion for models, but massive price erosion for models will be a signal that supply is massively outpacing demand. Token price must go down, but if price wars break out, we are probably overbuilt.

I believe, at my core, that supply is being built for future demand, which exists, but in every capital cycle, supply comes first.

Financing was Integral to Any Capital Cycle

I am starting to view the reflexive interlock between new capital cycles and capital itself as a key emergent feature. It’s no surprise that a rate-hike cycle coincided with the end of the telecom bubble. Greenspan’s hawkishness really kicked off the end, and the money supply often seized up, as the knock-on effects of the industry slowdown set in.

I sought to highlight how this reflexive connection manifested repeatedly in the railroad cycle. The 1873 cycle ended in part because of capital constraints elsewhere, which necessitated that American markets shore up liquidity. The 1890-93 cycle was similar, with British capital seizing up via contagion, amplified by gold flowing out of America, leading to an eventual implosion. The Panic of 1901 literally was a short squeeze. As we are on the precipice of a very large wave of lending, I also have to ask myself, is capitalism itself ready for it? More thoughts behind a paywall.

Metrics to Track

Now this is something only SemiAnalysis does, but I believe the aggregate fleet is an amazing metric to track. I also think the aggregate amount of capital spent is another super important metric. But last and not least is capacity utilization. When the railroad cars are empty, it is over.

Additionally, I think that railroads made me appreciate how closely linked capital and technology are. How much aggregate debt is now the focus, and the ability to service it, are major true goals of this cycle. Sadly, the railroad bubble was so overbuilt that it doesn’t even make sense from a modern perspective. All the railroads were built on speculation alone!

Anyways, for some final and very premium thoughts, I thought I’d leave where exactly are we in the cycle for last, because this exercise was enjoyable for me in terms of aggregate analysis.