The Three Tariff Problem

Chaos and complexity in a global supply chain

Before it was here, it was on Core Research at SemiAnalysis. The best and brightest in semiconductor research work at SemiAnalysis - reach out if you’re interested.

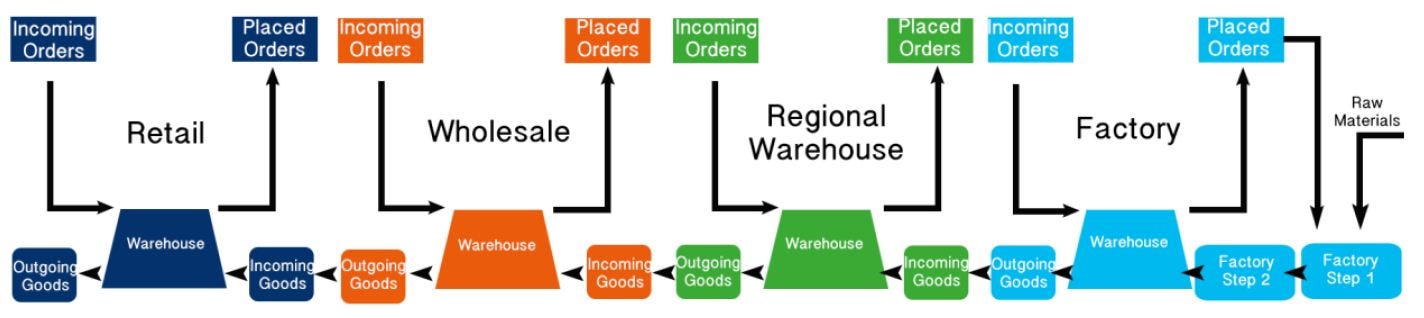

Last week, I read an excellent piece on “The Beer Game,” a supply chain game that discusses complex system dynamics. The game is pretty simple; four players do not communicate with each other and only exchange orders with their upstream partners and downstream partners.

The objective is to lower your company's costs, including the cost of carrying inventory and the price of maintaining a backlog. The game begins with a few rounds to get players familiar with it. Then, a simple demand change occurs, and an interesting (but indicative) thing happens every time.

Consistently, every time the game is played, whether with undergrads or with seasoned CEOs, there wind up being massive boom-bust oscillations in inventory.

Though individual games differ quantitatively, they always exhibit the same patterns of behavior:

1. Oscillation: Orders and inventories are dominated by large amplitude fluctuations, with an average period of about 20 weeks.

2. Amplification: The amplitude and variance of orders increases steadily from customer to retailer to factory. The peak order rate at the factory is on average more than double the peak order rate at retail.

3. Phase lag: The order rate tends to peak later as one moves from the retailer to the factory.

The actual demand change is simple.

And it is dead wrong. In fact, customer demand begins at four cases per week, then rises to eight cases per week in week five and remains completely constant ever after.

But this always stumps the players. And as over-ordering amplifies up the supply chain, the entire supply chain always whips into a frenzy of booms and busts. This is often called the bullwhip effect, and something I’ve written about in detail in the past.

The beauty of this “game” is that it's a perfect example of how multiple interlinking parts, namely the factory, the distributor, and the end retailer (I will refer to them as wholesale), can create disconnects and wild changes with minimal change in the underlying system. Minimal changes in one player can have almost impossible-to-predict downstream impacts. And if you’re a fan of science fiction, this sounds a lot like the chaotic outcomes of the three-body problem. There is no closed-form solution.

That’s why I'm calling this the “Three Tariff Problem” because this is precisely what's happening today. Because of tariffs, we just had one of the biggest pauses in the supply chain we’ve ever seen, followed by a resumption of orders that happened just today. That’s only a month, but if the Beer Game is correct, what’s to come will be pure chaos for orders, inventory, and finding out actual demand.

The Three Tariff Problem

Before I begin, I think an image of the Three Tariff Problem will put into vision what I cannot express in words.

I believe that at this point, every major part of the supply chain is in chaos. What does that mean for semiconductors? I don’t know, but I will try to make a generalized game theory analysis of what I currently see and what could happen. Let’s define the game, define the actions, and do some light forecasting. Remember, there is no optimal solution; we know that this is inherently chaotic.

Here are the players, which I simplify to retailers, channel inventory, and the factory. Outside of these are demand (which only the retailer knows) and capital expenditures (CapEx), which the factory has control over.

This time, this shock is happening from right to left. There is almost no demand shock (yet), and the tariffs insert themselves in between the channel inventory step and the factory step. In many ways, this will likely resemble the post-COVID cycle, where massive stimulus helped avoid a demand shock, and the pause in orders, combined with a shift from services to goods, created a significant pull forward.

This time, let’s kick this game off. Tariffs are in effect. The yellow order is pretty much the status quo, and most people aren’t reacting in a meaningful way. This is waiting and seeing what will happen.

This is today. We are seeing slight pull-ins in the semiconductor supply chain, specifically companies that are exposed to the consumer. Another important consideration is that the orders you do make are not your most exposed to tariffs, but rather your most profitable. We can verify this with Intel’s 7-nanometer shortage.

I’m going to assume that the base case happens. This is some form of tariffs remaining, and there is a deal in place to invest or buy US products in turn. Since investments are for multiple years and often require orders from overseas, I will ignore that impact for now. This is the longer-term solution, and will matter after we get through this inventory cycle.

But the most logical step is to burn down the inventory that you slightly pulled forward. Additionally, you are likely to pause orders if you can, because the end demand at the new price elasticity is uncertain. This brings me to the second phase. Demand remains the same, channel inventory gets depleted, and factory orders decline.

This is the period we are entering and will continue until we get some resolution. If nothing changes, what will eventually happen is a stockout. Even with the most positive resolution that returns business to normal, I believe we will see partial stockouts in the coming months.

As we see stockouts, visibility almost completely diminishes. Demand mechanically goes down as we cannot buy things. As with any chaotic system, a minimal change in the initial results can lead to significant differences in the outcome within a few months. The real question is, will we have a negative or a favorable resolution for tariffs? I think if tariffs come in at 10%, prices get passed on, this hurts, and then there’s a giant order rush.

But no one knows! There has yet to be a deal, and I expect the first one will set the direction. Let’s take Taiwan as an example - the one I probably have the most input into, or visibility into, if any.

Price Increases Likely

The most positive version of a Taiwan deal I can imagine is something like a 10% minimum tariff, with a significant concession from TSMC to build a gigafactory in the United States. Potentially, there could be a waiver for semiconductor products from Taiwan, contingent on continued investment in the United States’ manufacturing base. TSMC would likely absorb this through cost increases (they said they would on the call), and the net impact is a 10% increase to the consumer.

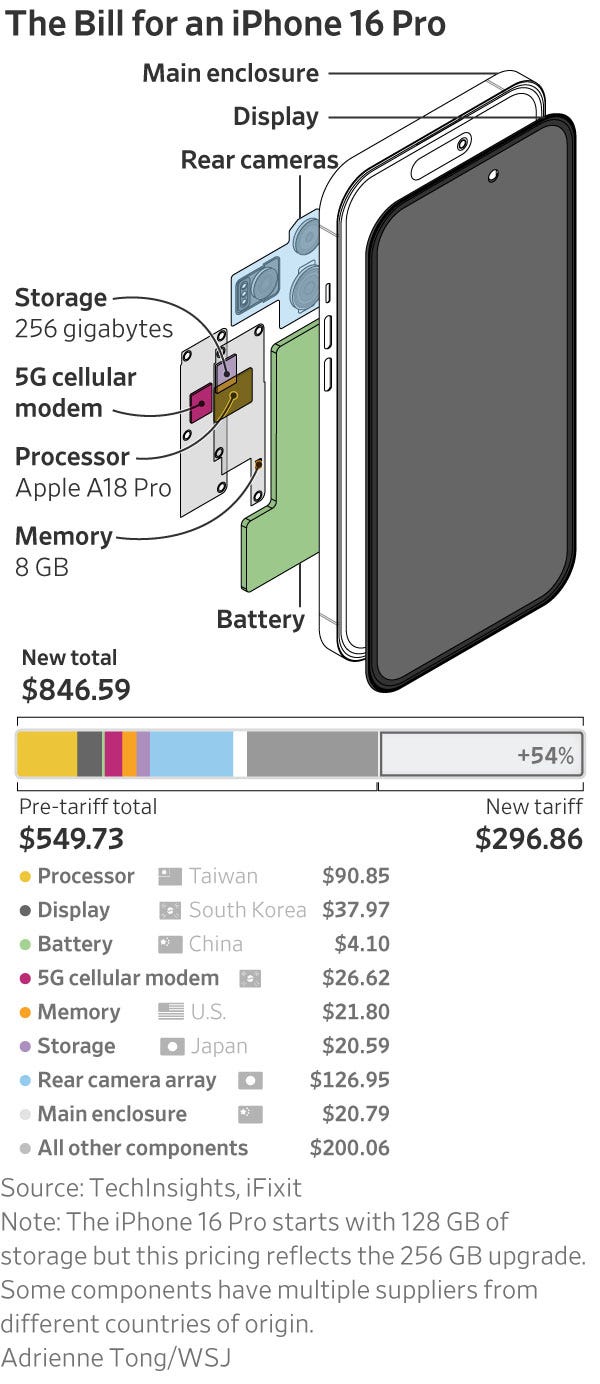

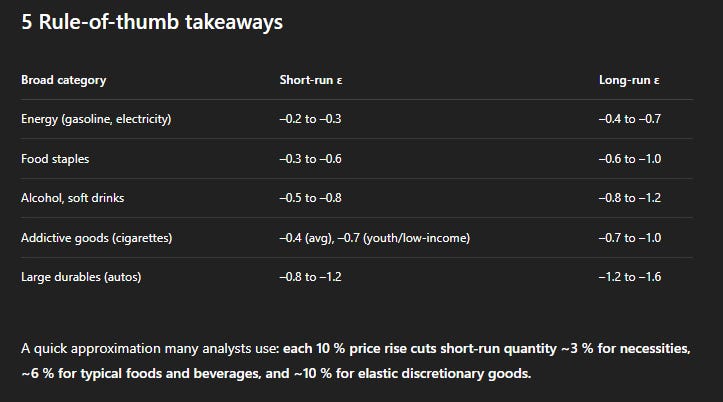

A further example is an iPhone. It’s a raw cost of around $550, according to The Wall Street Journal and TechInsights. Let’s assume there’s a raw gross profit of around 54%. Let’s assume that the costs are going up 10% in aggregate, as the rear camera array is probably not leaving China anytime soon. For simplicity in the analysis, I’m passing on 100% of the cost. The higher price will lead to less demand, but not 100% less demand; there is some elasticity. I had ChatGPT do a Deep Research into the elasticities.

Applying these elasticities to total PCE creates a price shock analysis. Some components are made here, exported abroad, then reimported. Additionally, there are considerations of intermediate goods. I account for both of these and come to a “final estimate”. The economy can handle a 10% flat tariff, but a 20% tariff would likely throw the economy into a stagflationary environment.

This is your simplified impact. PCE is growing at around 2.5% year-over-year, and 20% would cause the economy to contract, while 10% is a number that would indicate inflation and a middling economy.

Maximum Uncertainty

The problem now is, what do you do if you’re a supplier in this market? How should you order your chips in this economy? The irony is that there is a way to “solve” the beer game. It’s by ordering only your backlog and your expected demand for next week. That’s pretty much wait and see.

If things were quickly resolved, I would promptly rush orders to reflect that. If things are much worse, I would carry lower inventory as I expect demand to flatten. The reality is that while we live in a world where markets and supply chains are constantly speculating on the eventual outcome, businesses have to prepare for both outcomes (or a third outcome) at once.

The summary is simple: Chaos. Only 5 years after COVID, we are about to see another economy-wide inventory cycle. The last time led to stockouts, which then led to overordering as retailers overestimated demand, due to stimulus shifting purchases from services to goods. The collective economy was affected by inflation from rushed freight prices in 2021 and 2022, as well as an inventory glut in 2023.

There will be some supply chain chaos again. It won't be as bad as in the past, but it will still happen. Some of the most counterintuitive aspects of the Pandemic were specifically shown in automotive prices. It seems likely that we will get another round of automotive inflation. The bullwhip effect will impact the product or service with the most significant shortage, given that demand still exists on the other side.

Meanwhile, some of the pull forwards kicked off an inventory cycle that is unlikely to be stopped. A further (paid) conversation about automotive and consumer products is behind the paywall.