Are We in 1995? Rich Templeton's of Texas Instruments Thinks So

Rich Templeton of Texas Instruments made a comment on the cycle, TSMC's revenue accelerated again, and Intel seems to already be at the low end of the guide.

Thanks to all my paid subscribers and Tegus for sponsoring me. Support from my readers makes this newsletter possible, and I appreciate every one of ya’ll. Please consider subscribing if you enjoy this piece.

At the Citi conference last week, Rich Templeton of Texas Instruments made a comment comparing this cycle to the 1995-1996 cycle.

And the other thing, Chris, I know you're a historian in terms of trying to keep track of this stuff. To me, potentially the different -- the cycle you may want to go back and look at is '95-'96 and -- because 2000-2001, the Y2K cycle, emerged into a really pretty weak personal electronics market. The 2008-2009 cycle emerged into a pretty weak global economy because of the structural impact from global financial crisis.

And if you go back to '95-'96, you actually had what turned out to be an 8-year -- 7-, 8-year secular run with the growth of PCs and cell phones. Well, it isn't going to be PCs and cellphones in this secular run. It's going to be industrial and automotive because of semiconductor content. And so that may be -- and if you actually look at how pricing -- and it's a dangerous thing because of the way it's calculated as an average.

I agree and said so in my 1990s history piece! I think the 1995 and 1996 cycle’s fabrication shortage closest echoed this market, and I agree that the market is growing much more secularly than before.

Please pay attention to this part in particular. If you get anything out of this post, it’s that the 1995 cycle was likely one of the better analogies we have to today. When we look at today’s process, there is no cycle that I think is a better match than the 1995 cycle.

There’s a problem here, and that’s how you interpret how bad the cycle could be. 1995-1996 was a vicious downcycle, but the industry would emerge into a strong period as PCs continued to grow. Memory, in particular, had one of the hardest pricing environments ever. First, memory’s cumulative price went down 65% and then another 30%!

That would imply that Memory is about to be much worse than expected. However, I don’t think that’s what Templeton was getting at, but rather comparing how the end markets are still strong on the other side.

So let’s apply this case study to the semiconductor industry today. I want first to point out the differences before I get into the similarities. The most significant difference between then and now is Memory. The 1990s boom in Memory was much more pronounced than today’s cycle, and today’s boom has been primarily driven by logic.

Second, most companies are much more mature in terms of manufacturing footprint. There are fewer fabs and players in the industry than there were back then. For example, at the time 50 fabs for Memory were ramping, and nation-states were subsidizing the overcapacity. So what’s similar, and what does repeating the 1995 cycle look like?

If History Repeats Itself - 1995

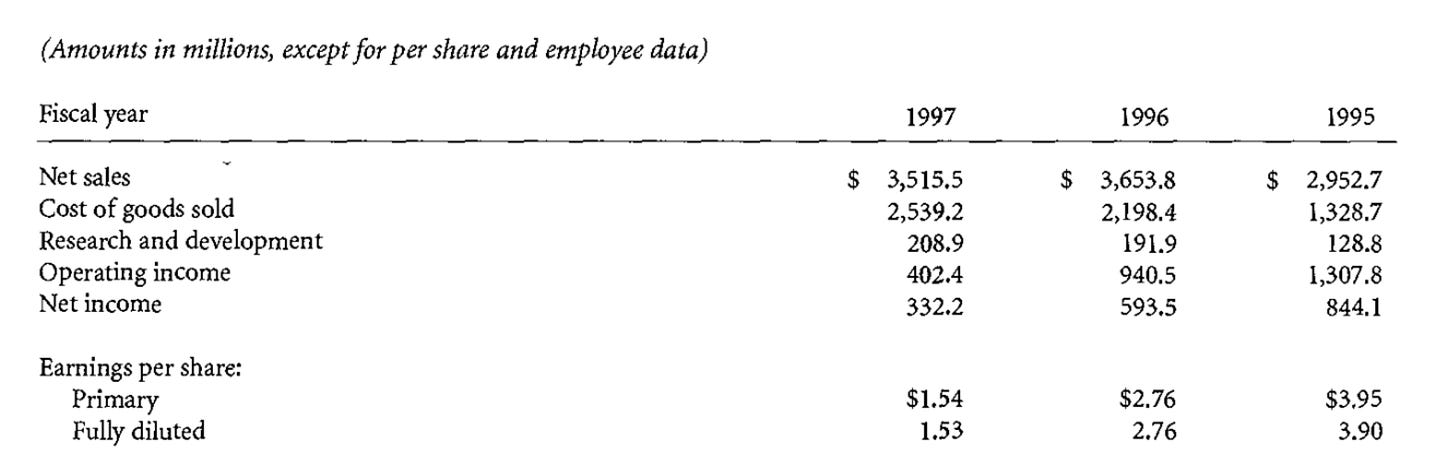

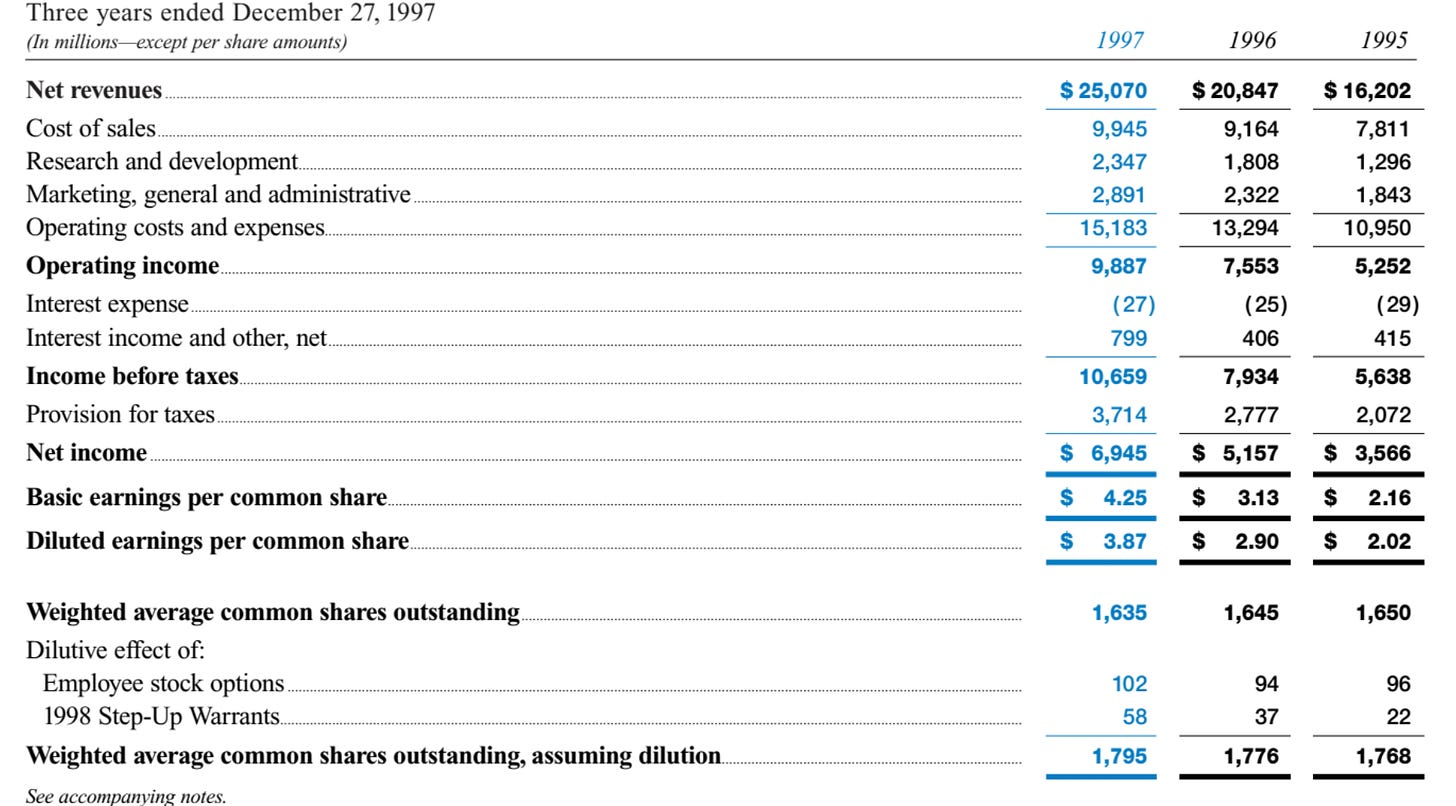

1995 and 1996 were pretty drastic times for Micron in particular. Intel, however, was a different story. It’s a tale of two cities, and the divergence between the strength at Intel and the weakness at Micron is what Templeton is primarily trying to get at. It could be a painful cycle, but the actual end state of the market is going to be much better than last time. That said, cycles are cycles, which could be painful for Memory, PC, and smartphone makers. An example is the financials of Micron below.

Revenue in 1996 and 1997 increased or stayed flat, but operating income went from $1.3 billion to 400 million over the two years. At the time, memory companies were profligate spenders, and memory companies invested during downturns to increase capacity even at the expense of profit.

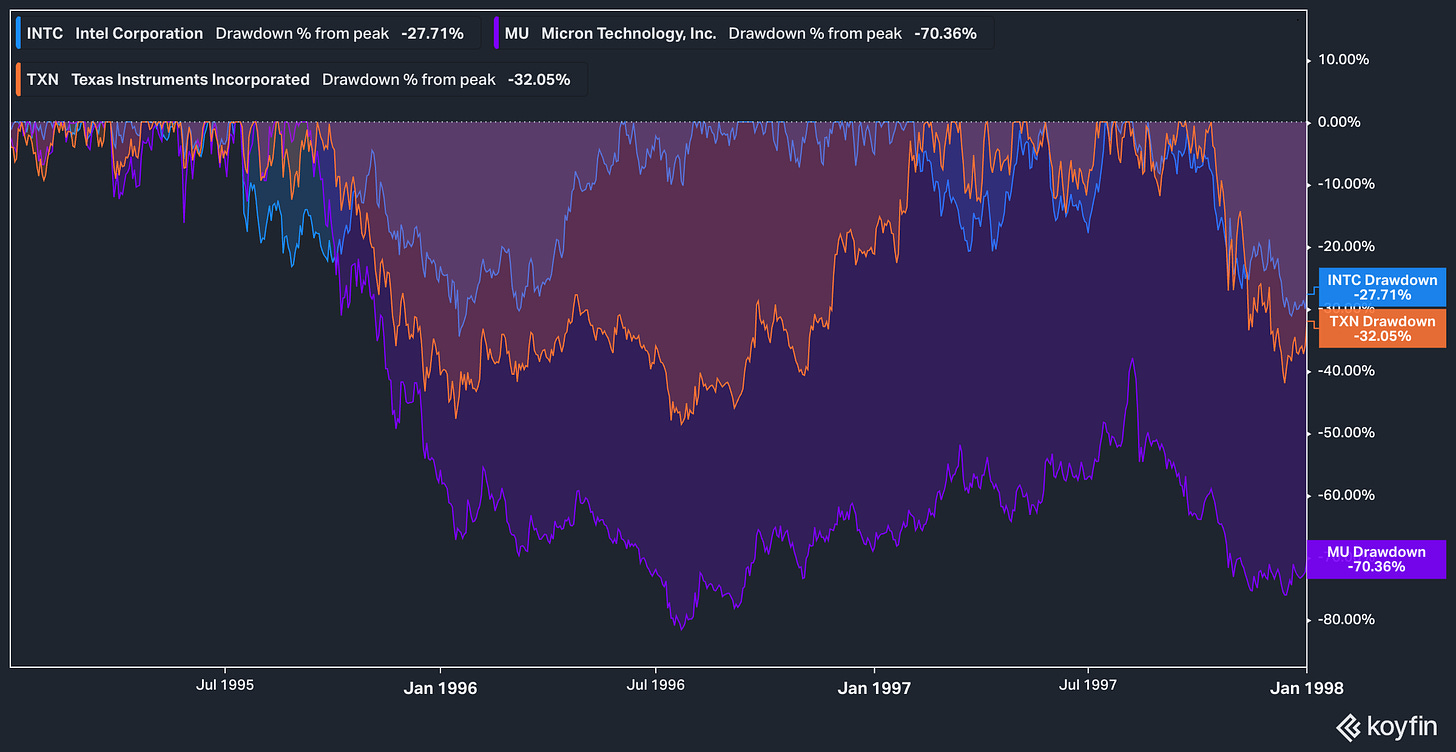

That’s a bit of a different story today, but the profits of Memory, PC, and Smartphone companies should shrink in this cycle. Also, their share prices should languish. Again, let’s take the example of Micron. Micron would be a 10-bagger from 1994 to the middle of 1995 and then have a 75% drawdown.

What is different is the number of players. I mentioned that at the time, over 50 new fabs were ramping for DRAM and 10s of players in the space. In particular, the massive overspending by the likes of Korea put fuel on the oversupply fire.

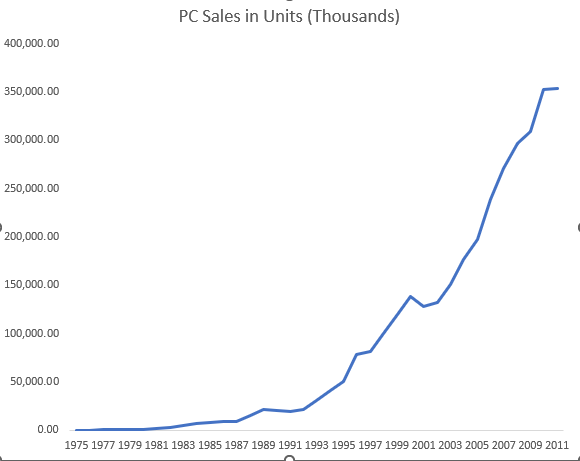

Today is nothing like that. But we can see the green shoots in the automotive, data center, and industrial markets. For example, 1995 was the heart of the S-Curve of PC adoption. PC sales would go from 50 million to 150 million units just five years later.

Templeton explicitly says this and that it’s not a synchronous downturn.

It's also a slightly different cycle in that it's not a synchronous downturn. And just look at second quarter, where one extreme, if you were in PCs, it was a pretty miserable quarter. And if you were in automotive, there was no change. And typically, if you go back to the bigger changes in late '08 and bigger changes in late 2000 and early '01, those were highly synchronized end-market corrections. And this one is a little different on that.

I believe this as well. As a result, PC and Smartphones will get hammered, while Datacenter, Automotive, and Industrial should continue their meaningful growth trajectory.

The conclusion here is unsurprising; you should be overweight the companies that have better exposure to that trend and underweight ones with higher exposure to PC and Smartphones. If you’re curious who's who - refer to my recent piece about segment exposures.

Let’s also look at the stock prices at the time and the eventual drawdowns that would happen during this context. Intel and Texas Instruments would have a 30-40% drawdown, and the more secular (Intel), the smaller the drawdown. Meanwhile, companies more exposed to the worst end markets like Memory had meaningful drawdowns.

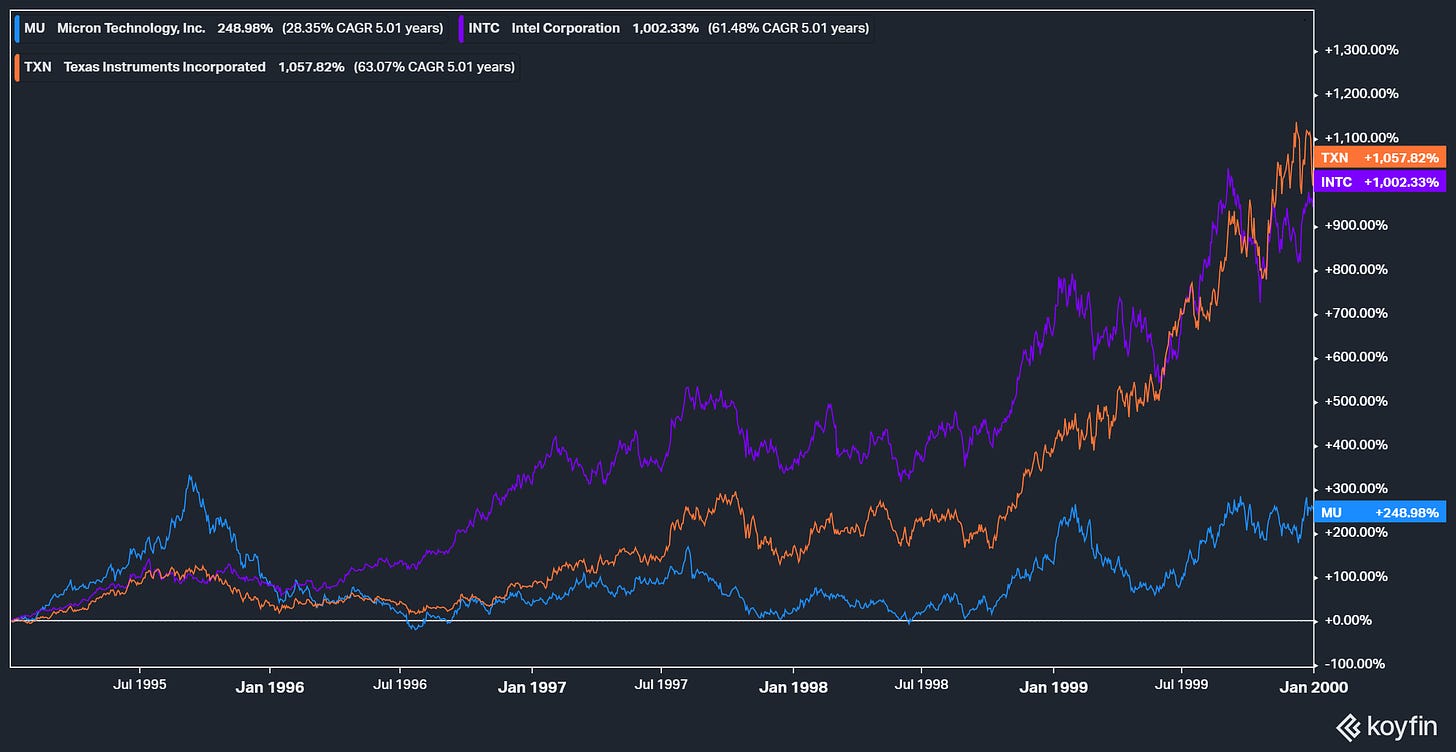

But if you zoom out, the companies themselves would go on to a strong end of the decade. Again, this was driven by solid end markets at the time.

Templeton and I both believe in the secular story. That is something I keep coming back to during the fear of this semiconductor cycle. This vicious cycle will likely hurt harder than the historically benign 2018 cycle. But on the other side, we are in the early days of Automotive’s rise. Industrial, IoT, and Datacenters should continue to do well.

If we are early days in these growth markets, the late 1990s period was one of the best periods for semiconductor companies. Meanwhile, the stocks already had a meaningful drawdown, setting us up for better future returns.

If Templeton is right (he should be!), we are about to set up into one of the better periods for the industry, and especially a reasonable period for companies that are positioned well for the next demand wave. Most of the downside has already happened in the stocks, as the typical 40% drawdown has happened for the average stock.

Now let’s turn to what it looked like for the secular winners of the 1995 cycle, in this case, Intel. The 1995 cycle didn’t impact them in the slightest for their operating profits because they were riding the big PC wave. Secular markets outweighed cyclical concerns.

I think there is a chance this is what automotive semiconductor companies could do in this cycle. Another market that seems to benefit from IoT as the proliferation of connected devices that is starting to penetrate industrial applications. I think it’s probably one of the better setups to purchase companies that are well exposed. And as a reminder of which companies to look for - check out my comp sheet.

Other News Headlines

Texas Instruments talked about what part of their capacity is not 300mm, highlighting their business's durability.

Yes. So I'll give you -- Dave can yell from the back if I have them a little bit off. But think of today, 80% of our wafers are on the inside. And over time, I think we talked in the capital management slides, that number will run up to over 90%. The math is pretty simple. We've probably got 60-plus percent of our assembly test on the inside. That number will approach 90% or over 85%, 5 years out in time.

300-millimeter is probably 40-ish percent of our internal capacity, and you play that out over time, albeit it's pushing 80% when you get out in 2030 because it's the only capacity we're adding. And we'll take a little bit of the final 6 in trough line as well. So those are 2 very important knobs to me in terms of if you want an indicator of competitiveness and the cost and dependability, okay? How much do you own? How much is internal? And what's your percent of 300-millimeter? That's the winning -- that's those are the winning variables you want to maximize.

It’s incredible to realize that Texas Instruments’ internal capacity today is still 60% 200mm and below! Most of Texas Instrument’s revenue is supporting products made before 2000.

Texas Instruments’ real exposure to China seems overstated on that comp sheet.

First is when we have in our annual report, whatever the percent of sold to revenue in China, 50-plus percent, I forget the exact number. And I'm always just very careful with that because of the manufacturing, that's not where it's designed in. And I get asked what's the real use of our semiconductors in China. It's probably about the GDP of China as a percent of the world. So I just -- that's probably what that looks like.

Multiple companies on my comp sheet were overexposed to China in this way, mainly because China has such a large percentage of the OSAT market. Therefore, in my opinion, one of the most critical imperatives for the CHIPS act is to decouple the supply chains, which needs to focus on OSATs in that equation.

Intel already thinks they are at the low end of their guide.

Since then, I think things have materialized pretty much as we expected, but even a little bit worse. And so we gave a range for our outlook on the call, something Intel never does. We always give you a number. This time, we gave a range, right, given that overall economic uncertainty at the time. And I'll say we're within the range for the quarter and for the year, but trending towards the lower end, right?

And things have generally deteriorated a bit more than we would have forecast earlier in the year, but still within the range for the quarter and the year. But it's pretty rough out there. And a lot of OEMs shifting views and outlooks, channel inventory adjustments and still a lot of economics to work through.

So all of that taken together, we'd say we're in the range, but a little bit more tepid than we would have indicated at the beginning -- or at the Q2 call. And essentially, every other announcement has been confirmatory of what we said so far in the industry. The few exceptions have very unique proprietary position on short nodes and technologies, and everything else just affirm that perspective.

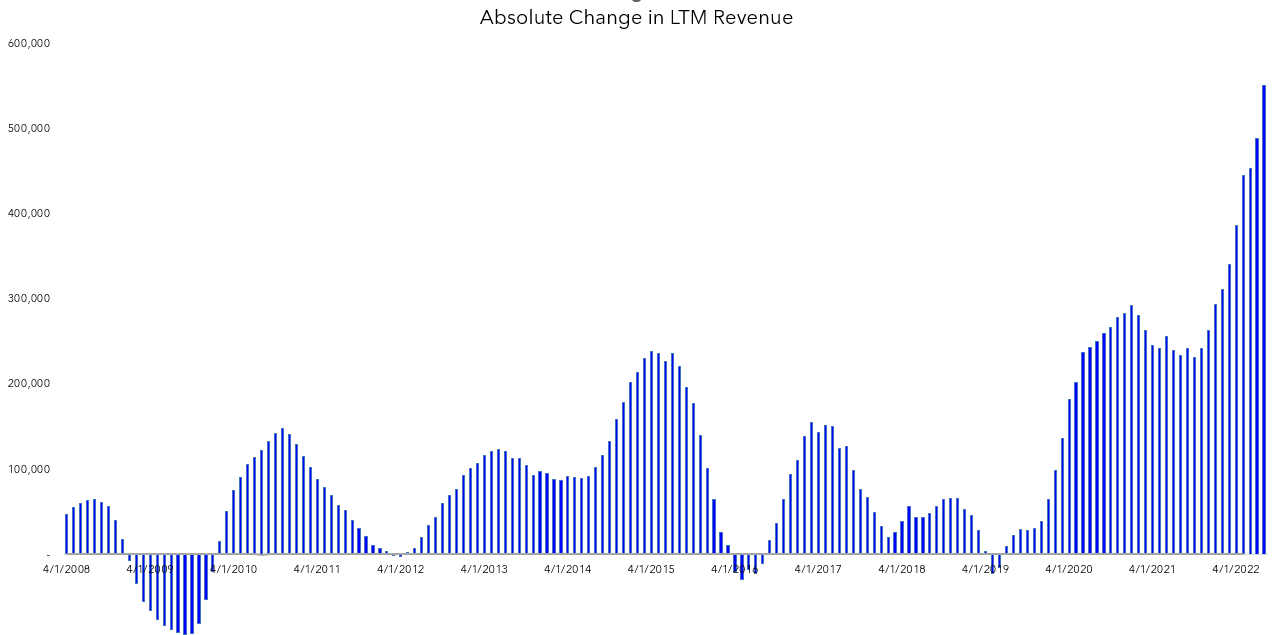

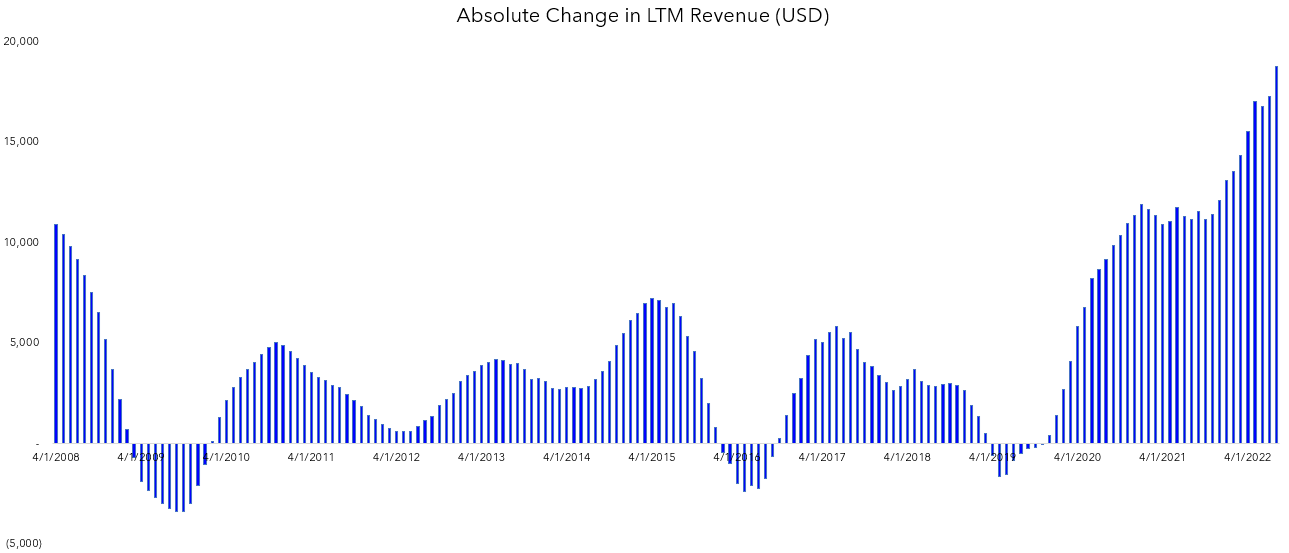

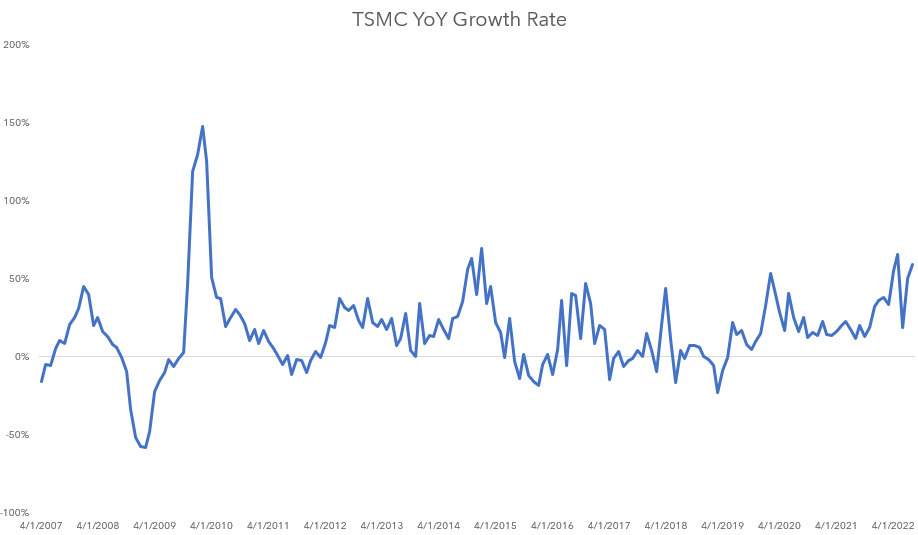

Last but not least TSMC’s monthly revenue came out, and the results are staggering. They managed to accelerate revenue again!

Revenue is accelerating in both Taiwanese dollar terms and US Dollar terms. For context on how to read these charts, refer here.

I also did just monthly YoY Growth rates; it’s accelerating! In TWD and USD terms.

This is so important because the stock price usually tends to go up when revenue accelerates and goes down when revenue decelerates. I understand that the market is concerned about the cycle's peak, but to see this amount of divergence is wild to me. EPS will likely grow 50% this year, but the stock is down 30%. Talk about a multiple contraction!

I don’t exactly know what to make out of this divergence. Despite all the fear of the semiconductor markets turning, the largest foundry continues to accelerate revenue. So it is going to be sold somewhere, right?

That’s it for this week. I am still working on some longer-term projects, which I hope to share with everyone soon. Talk then! -Doug

Great article!

MCHP Stephen Sanghi made a commented about a disconnect between what investors are expecting and what industry's been guiding to. Made sort of a 'this time it's different' comment about leading edge vs. trailing edge. What do you make of that?

Thank you for sharing this wonderful article.