Global Foundries S-1 Breakdown

A tale of two Global Foundries

Global Foundries dropped their S-1 last week. It’s been a long time since we last saw Global Foundries in public markets. The company originally was the fab segment of AMD that was acquired in 2009 by Mubadala, the UAE’s sovereign wealth fund. Prospectively, this looked like a good fit. For an economy trying to diversify away from oil with high current cash flow, might as well invest in one of the few global fabs. A match made in heaven. The actual transaction took time because it’s pretty hard to split an IDM (Integrated Device Manufacturer) into fab and fabless overnight. But it did happen and in 2012 Global Foundries and AMD split.

Since the semiconductor fabrication business is a game of scale, Global Foundries gobbled up more fabs like Chartered Semiconductor, in 2010, and IBM’s fab, in 2015. All while Global Foundries slowly fell behind in its ability to manufacture advanced nodes. In 2018 they realized that they couldn’t continue and did a “strategic repositioning.”

Instead of focusing on the most advanced chips, the Malta, New York-based GF would become a specialty chip maker and focus on various semiconductor niches. The company shifted focus away from continuing to 7nm platform and beefed up their 14/12nm FinFET platform and other specialty platforms. These are RF Silicon-on-Insulator (SOI), Fin Field-Effect Transistor (FinFET), Complementary Metal-Oxide Semiconductor (CMOS), Fully-Depleted SOI (FDX), Silicon Germanium (SiGe), and Silicon Photonics (SiPho). I’ll write about SOI eventually, but just think of these as a portfolio of differentiated products that are not as special as leading-edge but still hard to manufacture.

This was a good move. The world of semiconductors is not just going to be leading-edge, and one of the recent consistent themes is that lagging edge is just as in-demand as leading edge. Many of these technologies are going to be needed to push smaller form factors with less energy and other uses that are not leading-edge logic.

The timing of the IPO couldn’t be better, given a global semiconductor shortage, scrambling for capacity, and the need for local fabs. But taking a closer look, Global Foundries seems to be a tale of two Global Foundries, the company’s narrative and its financials. Let’s walk through each.

The Global Foundries Story

The qualitative business overview is compelling, and I loved many of the strong lines from the S-1. The consistent focus was We are the largest non-Asian scaled fab, and that matters in this current geopolitical environment. Try this from the S-1:

There are currently only five foundries of significant scale: GF, Samsung, SMIC, TSMC, and UMC. Collectively, these five foundries accounted for the vast majority of worldwide foundry revenue in 2020, according to a March 2021 Gartner Semiconductor Foundry Worldwide Market Share report. More importantly, approximately 77% of foundry revenue in 2020 was from wafers manufactured in Taiwan or China, with SMIC, TSMC, and UMC accounting for approximately 72% of foundry revenue in 2020. These trends have not only created trade imbalances and disputes, but have also exposed global supply chains to significant risks, including geopolitical risks. The U.S. and European governments are increasingly focused on developing a semiconductor supply chain that is less dependent on manufacturing based in Taiwan or China.

The writing on the wall here is that “Global Foundries is the only non-Asian scaled fab globally” (Samsung is Korean) and we are the best hope for U.S. and European semiconductor independence. Global Foundries is explicit that it should be a honeypot for subsidies. I believe it.

More from the S-1:

Against this backdrop, governments have been proposing bold new incentives to fund and secure their local semiconductor manufacturing industries. The United States Congress recently authorized the CHIPS Act, which, when funded as proposed by the United States Innovation and Competition Act, will provide for more than $52 billion in funding to the domestic semiconductor industry, with approximately two-thirds directed toward semiconductor manufacturing. In Europe, a program referred to as the IPCEI includes a large aid package to strengthen the EU’s semiconductor industry. These programs are designed to bring back share in the semiconductor industry to the United States and Europe by encouraging manufacturers such as GF to increase their local capacities in these regions.

Similarly, we believe that foundry customers are increasingly seeking to diversify and secure their semiconductor supply chains, and are looking for foundry partners with manufacturing footprints in Europe, the United States, and Asia, outside of China and Taiwan.

Meanwhile, they have a large market opportunity. They mention “A New Golden Age of Semiconductors” and give a waterfall of their TAM (it’s large) and then explain to us how their markets should be growing like weeds over the next decade. Each of them should grow mid-to-high-single digits except for Personal Computing.

They even give some interesting stats showing that a few of their customers really depend on them, and they’re diversifying from their large client AMD. This is a healthy sign that GFS can be a true fab with hundreds of clients, not just AMD’s washed-up fab.

Back to the S-1:

A key measure of our position as a strategic partner to our customers is the mix of our wafer shipment volume attributable to single-sourced business, which represented approximately 61% of wafer shipment volume in 2020, up from 47% in 2018. We define single-sourced products as those that we believe can only be manufactured with our technology and cannot be manufactured elsewhere without significant customer redesigns. Approximately 80% of our more than 350 design wins in 2020 were for single-sourced business, a record-breaking year in terms of number of design wins, up from 69% in 2018

These design wins in conjunction with the tight global supply problems have led to revenue commitments. This is a big deal for semiconductor fabs and is a relatively new phenomenon. This leads Global Foundries to proudly say they have more revenue visibility than ever before. Revenue commitments of $10 billion for 22/23 is $5 billion per year, slightly higher than their current run-rate revenue of ~$4.85 billion. But let them beat their own chests:

As of the date of this prospectus, the aggregate lifetime revenue commitment reflected by these agreements amounted to more than $19.5 billion, including more than $10 billion during the period from 2022 through 2023 and approximately $2.5 billion in advanced payments and capacity reservation fees. These agreements include binding, multi-year, reciprocal annual (and, in some cases, quarterly) minimum purchase and supply commitments with wafer pricing and associated mechanics outlined for the contract term.

Things couldn’t be better from a qualitative perspective. GF is in the right place at the right time during one of the biggest semiconductor capacity crunches in the last 10 years. Let’s see if the financials reflect that.

The Global Foundries Financials

Everything in the Global Foundries S-1 is great until you hit the first blue box of financials. First, let’s look at revenue.

First blush is terrible, but with some adjustments, including the ASIC disposition (I assume flat revenue) and the revenue recognition change, the business has only marginally declined. That’s still bad, but it could be worse.

The six months into 2021 paints a much better picture, however. Given the current headlines, this makes sense.

Thankfully, some growth has happened during the shortage, but it’s kind of a measly 12.6% YoY. Considering the environment, this is a bit underwhelming. Next, let’s look at gross profit.

I thought it was impressive that they managed to decrease the cost of goods sold from 2020 to 2021, but on closer inspection, that’s mostly a function of changing the depreciable life of their assets. They revised the economic lives of their tools from 5-8 years to 10 years, and that accounts for most of the cost-of-goods difference. I believe this is partially justified, as they’re pursuing lagging-edge opportunities and their current tools should have longer lives. However, this isn’t exactly clean gross-profit improvement. These are accounting gimmicks.

Next, let’s look at operating expenses.

Thank god they can keep their SG&A down and lower R&D, or this company would be staggeringly in the red. The S-1 says they believe they can scale SG&A with higher revenue, but I really doubt R&D is going to ever offer them operating leverage.

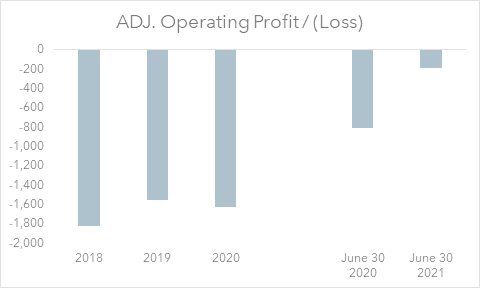

So that brings us to the horrid operating profit. (I’m not even going to bother below the line.) GF is extremely unprofitable and, barring some very significant changes, I don’t think they will ever be meaningfully profitable (15%+ EBIT margins).

I can see a narrow path — especially if they can drive the ~$5 billion annual revenue commitments and higher utilization, which could lead to better gross profits. Maybe just maybe they could eke out a meaningful gross profit and hold operating expenses down. But that road is hard and likely not going to happen. I have a hard time believing this company could ever be meaningfully profitable on a GAAP basis given this is one of the strongest cycles for fab demand ever.

The cash flow is so driven by depreciation and a litany of charges that I don’t really have much to say about it other than they’ve been stepping off the gas for capital spending. This makes sense, but without a meaningful capex increase I doubt they can really grow revenue quickly.

Lastly, I want to talk about their capital structure, which is of course a mess. I’m going to just skip the entire depreciation discussion. I want you to focus on the equity and paid-in capital line items. That’s 1) quite a lot of losses they’ve sustained since they’ve gone private and 2) a lot of capital Mubadala has put up — approximately $24 billion that’s kept the company afloat but not exactly thriving. Imagine a business that you’ve poured $24 billion into over 10 years and it’s currently Free Cash Flow breakeven and is going to need more capital eventually.

They have about $1 billion in debt, and let’s be generous and say their EBITDA is GAAP EBIT + DA and say that’s about $1 billion annualized, so 1x Net Debt/EBITDA. 100% of that EBITDA is D&A. In the fab business, if they didn’t spend more, the entire company would be shuttered very quickly. If things turn south during a capacity overbuild, they could run into debt problems. This is the curse of capital-intensive businesses. I would say that the financial situation is poor but not precarious.

The Financials Tell the Real Story

The company narrative just doesn’t hold up. When we looked at the management’s discussion and analysis, Global Foundry’s story is they’re the obvious non-Asian scaled fab. They make the argument that, given their narrower focus and the fact that they should attract money from governments that want to geographically diversify their supply chains, they’ll be spending less capital to participate in a secularly growing industry.

But what I see from Global Foundries’ financials is a subscale fab that is struggling to keep relevant and that’s been dragged along with ~$24 billion of capital infusion from Mubadala. All while barely squeezing out a gross profit and growing sluggishly in one of the hottest semiconductor markets of the last decade.

I see a capital-intensive business that’s barely FCF breakeven at the height of the cycle, that could see massive operational deleverage, and has enough financial leverage to be worrisome. When this company eventually has to access capital markets, either Mubadala will have to bail it out or watch out for massive dilution.

In fact, I think that this company’s financials are so bad that I don’t think investors are going to bite. I haven’t felt this strongly about a company in a while, but I would gladly be short this company the second it’s on the market. It screams funding short, and if that’s how I feel I can’t imagine what the appetite will be for the IPO. Global Foundries feels dead on arrival.

Oh, and if I were the U.S. government deciding on a desirablepartner, I’d choose TSMC or Samsung with a domestically located fab over a UAE-controlled dumpster fire. For all the talk about being a large European- and U.S.-based fab, over half of their wafer shipments are from Singapore. I wouldn’t choose a partner who at best can tread water.

Other Odds and Ends

Let’s not waste a juicy S-1 filled with data. Here are some other interesting things that I thought were worth learning about.

The big takeaway for the supply chain I got from this filing was “you should look at Soitec as a long.” I’ve been a fan of the company in the past but just check out this risk statement:

In particular, we depend on Soitec S.A. (“Soitec”), our largest supplier of SOI wafers, for the timely provision of wafers in order to meet our production goals and obligations to customers. We have entered into multiple long-term agreements with Soitec across a wide spectrum of SOI products. Soitec supplied 52% of our SOI wafers in 2020. In April 2017, we entered into a multi-year materials supply agreement with Soitec that expires in 2022, with automatic annual extensions unless terminated by either party. In that same year, we agreed to an addendum to the materials supply agreement for FDXTM wafers, in particular, as amended and restated in 2021. In November 2020, we agreed to an addendum to our original materials supply agreement to secure supply for 300 mm RF SOI, partially-depleted SOI and SiPh wafers. Our supply agreements with Soitec impose mutual obligations, in the form of capacity requirements, minimum purchase requirements and supply share percentages. We may be subject to penalties if we fail to comply with such obligations. If we are unable to obtain 300mm SOI wafers from Soitec for any reason, we expect that it would be challenging, if not infeasible, to find a replacement supplier on commercially acceptable terms in the near term.

Also, look at Wafer ASP. Global Foundries uses this slide to prove the point that they’re more specialty, but my thought process is “SOI must cost a lot.” This confirms previous research I’ve done on Soitec.

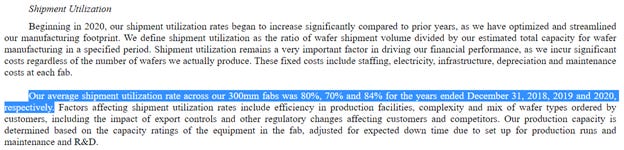

Lastly, I want to point out the utilization rate, which I thought was really odd. How is it possible that they only had 84% utilization in 2020?

The huge thing to note, though, is that “beginning in 2020, our shipment utilization rates began to increase significantly.” This is something to watch. Could they achieve 95%+ again? It seems like they must, given that UMC is at 100% capacity right now. This is the big thing that could change my mind. If utilization goes a lot higher in a short period of time, then the company’s financials could look a lot better very quickly. This is the big question you’d have to answer to get comfortable being either long or short Global Foundries.

If you found this post helpful, consider subscribing.

Well, that’s it for this S-1 breakdown. I hope you found it interesting. I think my big takeaway is I need to do some more work on Soitec again.

Intel won't buy them, they don't do production that way (copy exact). 10 year veteran of semi field, worked for gf for 5. Company started out OK but had a lot of difficulties with ramp and bad deals leading to decreased margins and stalled tech (Rip 7nm. Does anyone remmber 20nm). Then came the final nail in the coffin, IBM ''purchase''. Taking on employees that failed before and putting them in key positions to fail again. From SH to fellows (where do you think Tom came from). It wont get better.

Would this handicap AMD since AMD sources still most of its non leading edge capacity from GF? If GF falls behind further and further cuts R&D, could this drag down AMD?