Lessons from History: The Rise and Fall of the Telecom Bubble

The Internet and Telecom bubble. Lessons in leverage, rates, and a smattering of fraud. What can we learn from that period to compare it to the current AI infrastructure build?

It’s time for a history piece. I didn’t touch the internet and telecom bubbles in my last history piece, but I wanted to save an entire piece for it. I think it’s the best analogy for the historic boom in AI and infrastructure. Let’s see if there are lessons to learn from the past.

As a reminder, this is the latest in an ongoing series. Below are my first two history lessons:

I focus more on the Telecom bubble because it’s a better analogy to the semiconductor market than the internet bubble. Semiconductors are the public market picks and shovels for the AI boom, much like Telecom was viewed as the picks and shovels for the Internet.

Unlike in 2000, the pure AI companies of interest today are private or capped profit vehicles. So there’s a loss of visibility because they are private. AI will result in successful companies, but I believe many of the small AI companies of today will fail to make it. Tomorrow’s winners are probably born today, but that’s some time. What I think has the most direct analogy is the capacity building during the telecom bubble and today’s AI infrastructure spending splurge. So let’s talk about it.

1995-6: The Internet and Deregulation of Telecommunications

On April 30th, the NSFnet, the precursor to the internet, was decommissioned. This was the beginning of commercial and private internet use and where our story begins. Excitement about the internet was nascent then, and despite the high-flying late 1990s, the bull spirit was alive and well with the first internet IPO of Netscape on August 9, 1995. At the time, Netscape had the most market share in internet browsers but almost no revenue or profits. This would be the beginning of the speculative frenzy that culminated in 2000.

Once NSFNET was decommissioned, the optical networks were managed by Sprint, MCI, and AT&T in the United States. This state of the internet wouldn’t last long, and the Telecommunications Act of 1996 opened the gates to new entrants—the act’s goal was to promote competition in the telecommunication industry, especially in long-haul markets. Any communication business could compete in any market against each other, eliminating the natural monopoly status of long-distance telephone companies.

In one pen stroke, local telephone companies, long-distance telephone companies, cable companies, and emerging ISPs could compete. What’s more, they had to share their communication services and could buy and sell competitors’ network capacity.

This created a frenzy of entrants. New companies and established players alike threw their hats into the ring, and players Global Crossing, WorldCom, Enron, Qwest, Lucent, Level 3, and so many others had stratospheric rises and falls. Some of these companies were formed specifically in the aftermath of the deregulation. The key provision in the Act was the right for competitors to purchase services from them at fair rates and thus flesh out their entire network. This would create revenue accounting issues later.

Many companies started offering Internet Service Provider (ISP) services, building local networks where they could and purchasing wholesale bandwidth from network service providers (NSPs) when they could. ISPs work on the last mile, and NSPs provide backhaul.

The telecom equipment providers were on the other side of the network. Companies like Cisco, Ciena, Lucent, Nortel, and others were desperate to sell equipment to the frenzy of telecom companies building networks and laying fiber. In today’s analogy, they are the companies most similar to the semiconductor companies selling chips to AI companies.

Many iconic internet companies IPO’d in 1995 and 1996. Netscape and Yahoo IPO’d in 1995 and 1996. Yahoo’s first-day pop was an eye-watering 150%, which opened the eyes to what was possible. Amazon IPO’d in 1997. By then, demand was clear, and another 300 internet companies would IPO in 1999 and onward.

1996 was only the beginning. Telecoms and equipment vendors discovered that larger networks and scale meant more value, higher paychecks, and equity prices. Acquiring was much easier than building it out yourself. It also made comparisons of organic growth harder to understand. At the behest of bankers, a frenzy of acquisitions and IPOs began. The 100s of new entrants were rolling themselves together into large conglomerates.

1997 - The Beginning of the Acquisition Frenzy

To better set the scene, readers should know about one of the foundational tenets of logic for the build-out. According to WorldCom, internet traffic was doubling every 100 days. In 1998, the government repeated WorldCom's statement in 1997 and cemented this fact into the minds of the American people. In reality, internet traffic would double about once a year, meaningfully below this viral statistic.

This statistic was a big driver for the investment in IT, a huge portion of economic growth in the 90s. According to Mark Doms of the San Francisco Fed, ¾ of a percentage point of real GDP growth can be attributed to IT investment in 1998, 1999, and 2000. Real IT investment grew double digits annually for the entire decade. The absolute numbers of investment were staggering.

But the investment spending wasn’t completely unfounded. As companies began to add internet capabilities to their business processes, the U.S. economy saw one of the largest surges in productivity increases ever. In the latter half of the decade, hourly productivity increased a staggering 13% yearly! There was proof that IT spending was leading to a renewal in the economy.

It was hard not to be caught in the bull spirits by then. New technology quickly improved everyone’s lives; the proof was in the productivity pudding. Productivity growth did make it seem like the economy would achieve a new level of higher growth driven by increasing IT efficiency. Why not spend more?

The fake statistic of the internet doubling every 100 days made it seem like the world was improving at an exponential rate. This justified the intense IT investment at the time, especially in the Telecom sector.

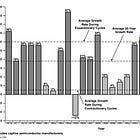

At the peak, telecom Capex was approximately $120 billion in 2000 dollars, or ~$213 billion in today’s dollars. This is one of the largest bases of capital ever built in such a short amount of time, and this capacity led to a glut in fiber that took almost a decade to backfill. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

The cumulative investment was well over $500 billion, including $800 billion in M&A in 1999.

Capital markets were happy to indulge and finance the spending. Banks issued equity and debt at levels never before seen, and one of the realizations quickly was that acquiring networks made more sense than building one.

It’s simple. There’s a power law in networks: doubling your network size usually increases its usefulness above that doubling. The largest networks usually had higher valuations, so the logic was to acquire your way into the largest network you could with inflated all-stock deals.

The amount of M&A is a special feature of the telecom era. The first few deals happened in 1996 and would go on to be the playbook for the telecom players. But when M&A activity peaked, over a trillion dollars in 2023 dollars were transacted in M&A in 1999.

The most famous deal was the WorldCom and MCI deal. WorldCom was the ultimate deal stock, and their marquee deal was acquiring MCI.

MCI was one of the key internet backbone providers at the time. MCI was the number two to the dominant AT&T and had quite a chip on their shoulder at their number two spot. When MCI’s founder, William McGowan, died tragically in 1992, the company floundered with failed ventures like a music trial system and an internet content business. By 1995, the plan for MCI was to sell itself.

In November 1996, British Telecom offered $24 billion for MCI. The merger hit snags, and BT lowered the price to $19 billion. That’s when WorldCom swooped in with the aggressive 30 billion dollar bid for MCI in 1997. WorldCom was ¼th the size of MCI. This bid came out of nowhere and shocked many.

But for WorldCom, this was the ultimate deal in a long string of deals. The company was always focused on growth through acquisitions and had already acquired several companies like UUNET, WilTel, and MFS Communications in 1995 and 1996. For familiar investors, WorldCom was the “deal stock” at the time, and WorldCom swallowing MCI was the ultimate deal. WorldCom closed the acquisition in 1998.

After merging with MCI, WorldCom bought Brooks Fiber and CompuServe, and shares peaked in June 1999. The ultimate deal of merging Sprint and Worldcom was attempted in 1999 but eventually was called off by regulators. Twelve months later, WorldCom started layoffs, and another 12 months later, WorldCom was in bankruptcy. The acquisition engine slowed, and then the cracks began to show.

WorldCom was not the only company enamored with acquisitions; Cisco, for example, made 45 acquisitions from 1995 to 2000. The frenzy started quietly in 1997, but after the success of the acquisitions, it rolled into a fever pitch in 1998, 1999, and 2000.

Meanwhile, players like Qwest, Level 3, and GlobalCrossing were just getting started. GlobalCrossing is perhaps my favorite, as it was a company that was raised for a dream. In 1998, GlobalCrossing did an IPO and then acquired Frontier. GlobalCrossing’s entire thesis was that we would need fiber connected to each corner of the world in undersea cables. The company was essentially a fundraising scheme looking for a problem. GlobalCrossing laid a huge amount of dark fiber that would take almost a decade to get used.

Despite all the bullishness, the fundamentals were “strong” at best. Revenue growth for WorldCom was just mid-teens. Check out the proforma revenue results for WorldCom in 1999. We are talking about ~11% total organic revenue growth. Despite the statistic that the internet was doubling every 100 days, organic results grew only a measly 57% yearly. But it didn’t matter; that was completely backward-looking; the future doubling would forgive all sins.

It’s worth also mentioning some economic background.

In 1997, Q1 GDP was growing at a staggering 4.3%. As mentioned above, productivity growth grew twice the long-term average, and the “new economy” productivity gains seemed unstoppable. The economy was running hot, but the Fed, led by Allan Greenspan, thought the productivity gains supported this. Inflation was low. This was the perfect market environment.

1998 - LTCM and Rate Cuts

Let’s talk more about the economic backdrop. It’s worth mentioning LTCM and the subsequent rate cut. This isn’t technically about the telecom bubble, but it significantly helped inflate equity markets. Rate cuts would be the fuel for the fire.

LTCM was a large hedge fund founded in 1994 with 2 Nobel laureates working for the company. It was among the most prestigious firms in the finance community, and the fund took levered bets against currencies and bonds globally. They applied academic finance at scale and with leverage.

LTCM had a rough 1998, with almost double-digit losses in May, June, and July. By August, the fund was down 44%, and on August 31st, stocks fell massively after Russia reneged on some of its debt. The LTCM owned a meaningful amount of Russian sovereign debt, and the fund began imploding on the default.

The big problem, as always, was leverage. At its peak, LTCM was 27 to 1 levered, and there was a concern that the disorderly wind down of LTCM would cause a financial implosion. The complex web of derivatives and positions would create price cascades, and there was concern that this could cause a systematic crash in financial markets.

Russia devalued its currency, and the devaluation sparked an international currency crisis. Most of Asia and Asian currencies are caught in the crossfire. Internet stocks were hit the hardest in August, with Amazon.com falling 20% and AOL and Yahoo falling over 15% in a span of weeks.

In comparison, the US was doing uniquely well at this point in time while the entire world was suffering. GDP growth was 5%+, and foreign countries and currencies were defaulting and failing. The fear was money would flee and run to the comparatively strong yields in the US, creating a toxic feedback loop. Alan Greenspan was aware of this and decided to cut rates, concerned that raising US interest rates would cause global contagion. The Fed cut rates in 1998.

This effectively was a Fed put at a time when the internet’s formative bubble began to form. While crazy activities in the market, like 100% a day IPO pops, were happening, the Fed was cutting rates. If we compare this to the SPAC craze and 2020, this sounds slightly familiar to some investors. This Fed decision is pivotal for the bubble as things go from crazy to insane. Markets went higher, and the party continued.

But I have yet to talk about the actual frenzy and Y2K.

1999 - Y2K and the Final Frenzy

Y2K was a unique cherry on top of the telecom and hardware spending bubble. Y2K refers to a famous computer bug caused by dates rolling over from December 31, 1999, to January 1, 2000. Computers and software used dates that only used the last two digits from the year, so many computers would interrupt the year 2000 as 1900, causing errors. Many companies rushed to prepare for the event, refreshing hardware that had the bug and purchasing software in anticipation of the date.

The event had few real-world consequences but was another narrative demand driver for a software and hardware refresh. This happening in conjunction with the internet bubble was just more fuel on the fire. This was spread among software, computers, and, of course, telecom.

Y2K is one of the weird confluence events that made 2000 so special. On the hardware front, Y2K forced an IT spending upgrade to ~$100 billion in spending, according to the Department of Commerce from 1995-2001. In conjunction with high-flying internet IPOs and the coming turn of the century, this created a special level of speculation and frenzy that I think is hard to replicate or appreciate. I’m sure some of my readers can attest. Y2K and the internet were all anyone was talking about.

If you look at the above spending charts and acquisitions, the telecom bubble’s froth happened mostly at the 1999 peak. That year, there were over 300 IPOs of internet companies, and most investors and media participants were discussing how the internet would lead to unprecedented growth. And while the internet did grow to be a meaningful part of our lives, societal change rarely happens that fast.

Many companies peaked in share prices in 1999 or early 2000. The Nasdaq had returns of 80 and 100% in 1998 and 1999. 1999 was truly a special year.

Between the start of 1999 to April, the Dow Jones doubled. Mary Meeker, a prominent internet analyst, predicted internet companies would fall in a year, and there was a dramatic 20% correction in late April. The entire country was gripped in a speculative fervor, and stocks traded with immense volatility.

But by the end of 1999, it was clear that the bull market was still alive. Companies like AOL and Yahoo share prices rocketing more than 500% and Amazon over 900%. Sadly, the good times rarely last. The market would crash in 2000.

I want to examine the fundamentals underlying this speculative rise because while things were good, we are not discussing great. Share prices massively outgrew even the best performers’ fundamental results.

Revenue grew in 1999 at a torrid rate. But let’s take Cisco, one of the poster children of the hardware spending bubble; revenue grew 55%, up from 43% revenue growth the year before. EBIT growth was meaningfully below revenue, driven by higher R&D spending.

Revenue and EBIT are faster than in 1998, and acceleration is usually good. But for context, WorldCom grew “organic” (inflated) revenue at 28% on a proforma basis, compared to 11% revenue the year before. We are not talking hypergrowth operating statistics but hypergrowth in multiples of stocks. The clear driver of stocks in 1999 was multiples and hype.

But under the surface, it wasn’t just stocks pushing their limits. The companies began using aggressive accounting and financing tricks to prop up growth. For example, networking equipment suppliers extended credit to networks, which were massively levered already. The 2000 bubble was a unique example of leverage at an unprecedented scale.

This couldn’t last. In conjunction with the internet bubble popping, Telecom and hardware felt the impacts in 2000. But per usual, it’s all about the Fed. In early 2000, the Fed acted and began a short rate hike cycle that popped the bubble.

2000 - Internet Bubble Pops

If 1999 was a frenzy, the hangover began in 2000. Shares peaked in 2000, and the Nasdaq finished the year down 30%. The internet bubble popping slammed the breaks on many of the telecom and equipment providers. And when the engine slowed down, many haphazard methods used to keep the train going also broke down.

What exactly broke the internet bubble? There are many possible things, but I want to highlight the most the fed.

On January 14, 2000, Greenspan gave a speech giving his rationale for holding back the market: the wealth effect. This would effectively begin a change in tone at the fed, and the Dow Jones peaked that day. There was carnage ahead.

March of 2000 was the final peak for the Nasdaq, and internet stocks were at an all-time high. The internet index at the time was up 130% over 12 months, but the good times wouldn’t last. The fed would begin a serious hiking campaign in 2000 that would shake markets.

When the activity of the internet companies slowed down, it became very clear that most companies had pushed past their limit.

The severity of the correction was immediate. From March to April 2000, companies like Yahoo, DoubleClick, eBay, and Amazon fell between 30 and 50%. Akamai, Commerce One, and Internet Capital Group had declines of over 70% in a month. The self-fulfilling prophecy of stocks going up had ended, and now the speculative fervor became a hangover.

By August 2000, the PMI (purchasing managers index) dipped significantly and signaled further industrial weakness. In August, at Jackson Hole, the Fed felt that they had slowed the excess, yet the economy was still growing at a meaningful pace. But this was missing the microeconomic news. In September of 2000, Intel gave a revenue warning and fell 40% in a day. The bullwhip effect in semiconductors and networking equipment was at play now.

It was clear that orders everywhere were falling by October, and the great tech bubble had burst. Pets.com, one of the poster children of the bubble, closed up shop in November. Ebullience was gone, and reality had set in. And now that the tide was out, it was time to see who was swimming naked.

2001 - Telecom Bubble Bursts, Enron and WorldCom

Now layoffs were happening, and the economy was slowing so much that the FOMC cut rates in January 2001. But it was too late. Cisco started layoffs in March, and shares crumbled. Cisco was bullish late into the cycle, with huge backlogs that became excess inventory writedowns. The boom in spending became a bust almost overnight, with IT spending contracting 30 billion from the year before.

This is where the story takes a dark and fraudulent turn. Telecom companies, in particular, had taken the most drastic measures to juice revenue growth, and the entire accounting engine was breaking. I’m talking about WorldCom and Enron, the two largest bankruptcies in modern history.

Enron was outright cooking books, often using affiliated entities to pass through revenue to the main entity of Enron. Mark to market was a huge lever, as they booked contract revenues to “true economic value,” meaning that they then marked their own NPV for a gas or telecom trading contract. Enron also bought and sold telecom capacity and booked a 20-year agreement to supply Blockbuster for streaming. When the deal failed, they were still booking revenue and profits. The gig was up.

Enron, in particular, was outpacing the underlying telecom industry and was being asked about the accounting issues on calls. Jeffrey Skilling began to attack analysts. One of the most famous conference call responses of all time comes from this period, between Jeffrey Skilling and notorious (derogatory) telecom analyst Richard Grubman.

“Well thank you very much, we appreciate it, Asshole” - Skilling

Blood was in the water, and it was clear all was not well at Enron. Enron revenues tripled year to date by July of 2001, despite the entire industry slowing down. In August, Skilling resigned from the CEO role and sold over 35 million dollars in stock. A VP at the time sent an anonymous letter to the board, and it was clear that the company was fraudulent, and the letter expressed concern about an accounting scandal.

In October of 2001, Enron announced restatements. They reduced profits by 23%, and heads began to roll at the management team. The crisis was just beginning, and later, Arthur Anderson, one of the Big Five accounting firms, was found guilty of helping to perpetuate the fraud. Enron was in the business of inflating revenue and was one of the largest companies in the world at the time.

Meanwhile, the WorldCom story starts in late 2000, when WorldCom began to book capital expenditures as expenses rather than capex. This is tax fraud, and by June 2001, it became apparent that the company had been cooking the books. The CFO at the time, Scott Sullivan, blessed this, and internal audit VP Cynthia Cooper found it. Cooper called a WorldCom board member to discuss the matters but was discouraged. The slew of acquisitions was not working, and there were over 3 billion dollars in prepaid capacity entries, shifting capex to expense.

In June of 2002, the SEC began an investigation, and the whole financial house collapsed. WorldCom had overstated profits by $3.8 billion against ~$30 billion of debt. WorldCom declared bankruptcy on July 21, 2002.

One of the big reasons for so much fraud in the telecom industry is that the entire industry at the time had pushed itself to the limits. Between mis-expensing capital expenditures, vendor financing, and buying and selling revenue between competitors, the entire telecom industry had engaged in aggressive tactics to show better numbers. And if you didn’t participate, you were left behind. The incestuous ties created many opportunities to double-count revenue while undercounting expenses.

Almost every major telecom company had to restate 1999 and 2000 numbers. This was not an Enron or WorldCom problem; it was industry-wide. The bubble burst, and the speculation and aggressive accounting were shown widely.

Lastly, September 11th, 2001's tragic events shook the American public’s confidence. This was the final death knell for the bullish spirits in America. The 2000-era frenzy was over.

Similarities to Today

Now it’s time to learn some lessons. This is probably one of my favorite exercises because not only did I learn a lot about past markets, but I think I learned a lot about today’s market. The 2020 SaaS and SPAC lead bubbles had many similar excesses.

I will cut the similarities and differences I see into two broad categories.

Scaling to “bigger” networks or neural networks

Capital intensity for Telecom and AI were high

One of the scariest comparisons to the Telecom bubble is the doubling demand every 100 days comparisons. OpenAI in 2018 said that demand for training is doubling every 3.5 months. It’s uncanny because 3.5 months is about 100 days, which feels like an old meme reborn. If we were to compare the time frames, this was said in 2018, and the internet statement was made in 1997. So we would be “overdue”. Most people would agree that training demand has slowed and that statistic has lessened power over us than it did back then.

The demand doubling every 100 days also brings up a similar feeling: if we only had more bandwidth or AI computing, we would hit a new economy high. And that bigger is always better, no matter the cost. There is a blind belief in scaling to even bigger neural networks without much consideration for cost. The same mindset was true in 2000, and fiber per capita spend was north of 500 dollars per person in 1999. If we build it, they will come, was the primary logic then. That similar logic of building better models rings true today as well.

Something is appealing about the logic. Exponential progress was believed to be possible because of the internet, and better larger AI networks rhyme with increasing internet capacity for an exponential future. There’s a lot of spending on potential business models, with an estimated $100 billion in AI spending in 2024. There isn’t that much business model on the other side to support that, especially if that number were to increase again.

Another difference I have to mention is that the capital intensity for telecom and AI is so high. Fiber investment hit 1000s of dollars per capita for the cumulative spending in the Telecom bubble. If we were to equate the per capita and population size changes, we would be talking ~$1.2 trillion in AI investment. The telecom industry was spending billions of dollars in investment without much of a business plan, believing it would eventually be recouped. Today’s investment feels very similar. Both AI and telecom are capital-intensive in a way that software never was. That’s an important comparison.

The capital intensity and a bubble have a way of rhyming with many other traditional bubbles in history. Every large technological change has a huge capital rush before it. Railroads, Canals, Trading Route monopolies, the Internet, and AI all had huge capacity additions in conjunction with bubbles centered around huge capital additions. Something about spending for a gold rush in the future is appealing to humans. I want to highlight the technological revolutions and financial capital book by Carlota Perez. This has happened before, and this could be another example of this happening again.

We see another example of the long line of history lessons. But looking through this framework, the AI bubble is hardly frothy, just a drop. Things can get much crazier from here, especially if rates were to drop like 1998.

How the Telecom Bubble is Different

However, the similarities pale in comparison to the differences. The telecom bubble was truly unique and an amazing financial bubble. There are a few great differences for me.

Leverage

The Barrier to Entry in the market was lower

Rates

Leverage is the defining difference between the telecom bubble and today. The telecom bubble had compounding levels of leverage throughout the value chain. The network equipment companies supplied leverage to the networks, financed by debt, and often acquired their competitors with even more debt. There were hundreds of billions of dollars of debt at stake. Compared to today, almost none of the big AI companies are leveraged.

Let’s compare Amazon, Microsoft, Google, Meta, and Nvidia. Except for Amazon, almost none of the companies carry net debt. Meaning the average company has excess cash over debt.

The capacity to raise leverage for large companies is staggering. The big players could easily raise 100 billion in debt (if the market could stomach it) and reach debt neutral. That is a lot of potential firepower for AI purchases. This analysis is a bit hypothetical, as the current rate for debt is high, a conversation for the rates portion of the differences.

The barrier to entry in telecom seemed so much lower than building a foundation model. When deregulation happened, new entrants did join the ranks of telecom. I think there is an analogy between internet companies and AI wrapper companies, which have had many new entrants. These companies are trying to utilize foundation models to create business models, and VCs have supported many of these companies. Many will not make it, but a few will become real companies.

This comparison of internet companies (AI wrapper) and telecom (foundation models) is my favorite analogy. In this analogy, Cisco is Nvidia, except that Cisco has competition while Nvidia does not. AMD is not quite an Alcatel or Lucent. Jensen’s shrewdness has mostly been making an effective walled garden for the capital equipment for a uniquely capital-intensive pursuit. There is no comparison, and the entire AI training infrastructure flows to just two players, Google but mostly Nvidia.

Last but not least, I want to talk about rates. The entire AI build-up so far has happened during a rate hike cycle. Nvidia’s revenue has gone parabolic during a Fed hiking cycle. This doesn’t mean that this cannot be an overbuild, but it helps prevent probably the worst of speculative tendencies. This huge amount of gravity for capital spending is happening simultaneously with Nvidia’s historic rise.

This begs the question: what the hell would happen if rates were to be cut? We are closer to the end of the hike cycle than the beginning, and I think that could be a new leg of frenzy if rates were cut. There are concerns about the economy, and if rates went down, I would be curious to see what would happen.

I want to make one final comparison. During these demand hype cycles, supply is always an underappreciated part of the story. I think that supply is an underestimated part of the picture.

Supply Reacts to Demand

The last comparison to today I want to leave you with is that supply and demand are reactive. Part of the bubble overbuild that led to a collapse was that supply couldn't react fast enough while demand was high (the internet doubled about yearly). But necessity is the mother of invention, and supply, in the case of the internet bubble, grew much faster than demand.

I enjoyed the Craig Moffett interview at Stratechery because supply reacted quickly to the deluge of internet math. And if you did the math like Craig Moffett, you’d see that supply beat out demand in the end. This is a quote from the Stratechery interview with Craig Moffett.

Craig Moffett: We did the math, and it turned out that the industry had increased capacity over the span of the prior seven years by 186,000 times.

When the fiber and infrastructure were built, people realized the incoming supply created a glut. According to the WSJ, only 2.7% of fiber was being used in 2002 after the overbuild in the internet. Between the new fiber being laid, the denser strands, DWDM, and new IP standards, there was a 100,000x increase in supply.

One of my favorite examples of this impact is ethernet roadmap speeds. From 1995 to 2002, ethernet would increase 100-fold. The next 100x in speed took over 20 years, and today, ethernet is starting to accelerate again, given the networking bottleneck for AI training.

Let’s compare this to AI today. Everyone is GPU-poor and constrained today, and the leading-edge models we want to train are constrained by computing, memory, and data. But if history is a guide, supply reacts to demand.

Recently, Nvidia released a new roadmap pushing the cadence of product announcements to every year from every other year. This is a perfect example of supply reacting quickly to demand.

I expect each generation to be about a 3x increase in performance for 50% more price. Doing the math on that, we should expect a 9x increase in performance from 2023 to 2025 (H100>X100) and a 2.25 increase in price, leading to a 4x increase in TCO.

Moreover, Nvidia is working hard to increase fan-out ability, meaning the number of GPUs you can have in a fleet. Capex is skyrocketing, so the supply coming online to react to demand will eventually meet and likely overshoot. A 4x TCO increase plus more spending means the hyperscalers will likely buy 10x+ more compute next year than in 2022. There’s a lot of training demand, but supply is reactive and will eventually deflate overshoot. It’s not a question of if but when supply will overshoot demand.

If you found this piece helpful, more than anything, I would appreciate it if you shared this post. It is a big deal to me whenever someone reads my work, and I appreciate your support.

If you’re curious about my sources and some really interesting comp sheets, here’s a great place to start. I mostly relied on books, but there are a lot of helpful links below as well. If you have any questions, feel free to comment. There’s a lot of content here, and I’m sure I’ll make some mistakes. Now it’s time to move on to earnings season.

Appendix

Books

Capital Account by Edward Chancellor

Telecosm by George Gilder (this was a hilarious read)

Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital

Articles / Links

https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/er19-34bk.pdf

https://news.viasat.com/blog/satellite-internet/a-brief-history-of-internet-service-providers

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Telecommunications-Act

https://internationalbanker.com/history-of-financial-crises/the-dotcom-bubble-burst-2000/

https://www.yardeni.com/pub/capspendrdtech.pdf

https://extreme-events-finance.net/resources/ltcm-crisis/

https://www.sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/lr-18147

https://money.cnn.com/2002/07/19/news/worldcom_bankruptcy/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Global_Crossing

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/wallstreet/wcom/cron.html

https://www.chron.com/business/article/timeline-of-the-history-of-worldcom-2115927.php

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Qwest

https://www.internetworldstats.com/emarketing.htm

https://www.fcc.gov/general/telecommunications-act-1996

https://www.princeton.edu/~starr/articles/articles02/Starr-TelecomImplosion-9-02.htm

This was a great article! Brings back memories of those days as a fingerling in the industry. One could see a lot of it for sure but hindsight always seems clearer.

I’m curious if you were working at the time and lived through all the craziness?

THANKS!!!! I forwarded this to multiple mailing lists I am on, like internet history an my new nnagain list which has ol farts like me on it: https://lists.bufferbloat.net/pipermail/nnagain/2023-November/000344.html