Industry Structure: Fabs are in Favor - LTAs are the Tell

Long Term agreements, particularly the NCNR order is a relative newcomer this cycle. Let's see how they are holding up. The Industry Structure is showing that Fabs are in charge.

I got a great shoutout from the newsletter I respect the most - Stratechery. He shouted out my Nvidia 40% QoQ decline call. He was right that I expected this to happen in the next quarter, but regardless happy for the recognition!

These weren’t Nvidia’s official earnings, which are offset by a month from everyone else (i.e. the most recent quarter just ended on July 31); the miss was significant enough, though, that the company issued a warning. Credit where credit is due: Doug at Fabricated Knowledge forecast this miss after last quarter’s earnings, thanks to his longstanding focus on the cryptomarket and the impact it had on Nvidia GPU sales:

Other than the shoutout, I want to talk today about something that is becoming increasingly clear after Nvidia, Qorvo, and Globalfoundries earnings, the fab and fabless relationship is changing.

Oh, and psst - Thanks again to Tegus. Their continued support of the newsletter helps make my content better for everyone. I expect to do some work on SiTime soon in conjunction with Tegus. I’ve found their calls to be extremely helpful for getting up to speed. If you find this newsletter useful - consider subscribing!

The Changing Nature of Fab and Fabless

One of the things that I have found so fascinating about this inventory cycle in the semiconductor industry is the NCNR (non-cancelable, non-refundable) order. The reasoning behind the NCNR is that investing in a wafer fab is expensive, and recently those costs have been increasing; thus, fabless customers should have to bear some of the financial burdens of investing in a wafer fab and cannot cancel their orders. Foundries and Fabs have managed to enter long-term agreements with most of their customers, whether it’s the demand planning at Micron or the NCNRs at Globalfoundries and the like.

Note: I will refer to foundries and fabs interchangeable in this piece. A fab is the actual building where semiconductors are made; a foundry is a company that sells that building’s production as a service.

Let’s contrast this against history - when Fabs were thought of as cost centers, outsourced to Asia, and disposed of at the earliest possible convenience for the fabless company to flourish. If there is a pendulum of the importance of having a fab, we likely swung from peak fabless and fab-light to a geopolitically fab-hungry world. The entirety of 2020 amplified that.

The 2020-driven shortages highlighted the strategic importance of fabs, especially in industries like automotive. As a result, most companies had to rethink how to treat fabs and stopped treating fabs like an infinite and elastic supply pool when it is a strategic supply if you’re selling electronic goods.

Furthermore, Intel and even Samsung have started to struggle as foundries get smaller and smaller geometries; we realize that making chips at the leading edge is a challenging endeavor. TSMC has pulled away as the leading global foundry. Still, now the world's largest and most essential wafer fabs are concentrated in Taiwan, an island nation roughly 100 miles off the coast of a larger country that lays claim to its sovereignty. It’s a strategically complicated situation.

Companies and countries want to diversify their semiconductor supply, but making a fab is hard. Money is just one part of the equation; an entire Taiwan ecosystem is hard to replicate globally. For fabs to re-shore, it will take a heavy and consistent investment. So now the fabs are leaning on their customers.

Like ASML required a heavy co-investment from their customers (TSMC, Intel, Samsung), fabs require co-investment and risk sharing of capacity with their customers to better weather the semiconductor cycle. This comes from the LTAs and NCNRs that fabs are entering with their customers. To a certain extent, their customers don’t have a choice. This is all an expression of a changing industry structure of fabs and fabless. But before we talk about what I think will happen in this cycle, let’s take a quick step backward.

A Brief History of Fabs and Foundries

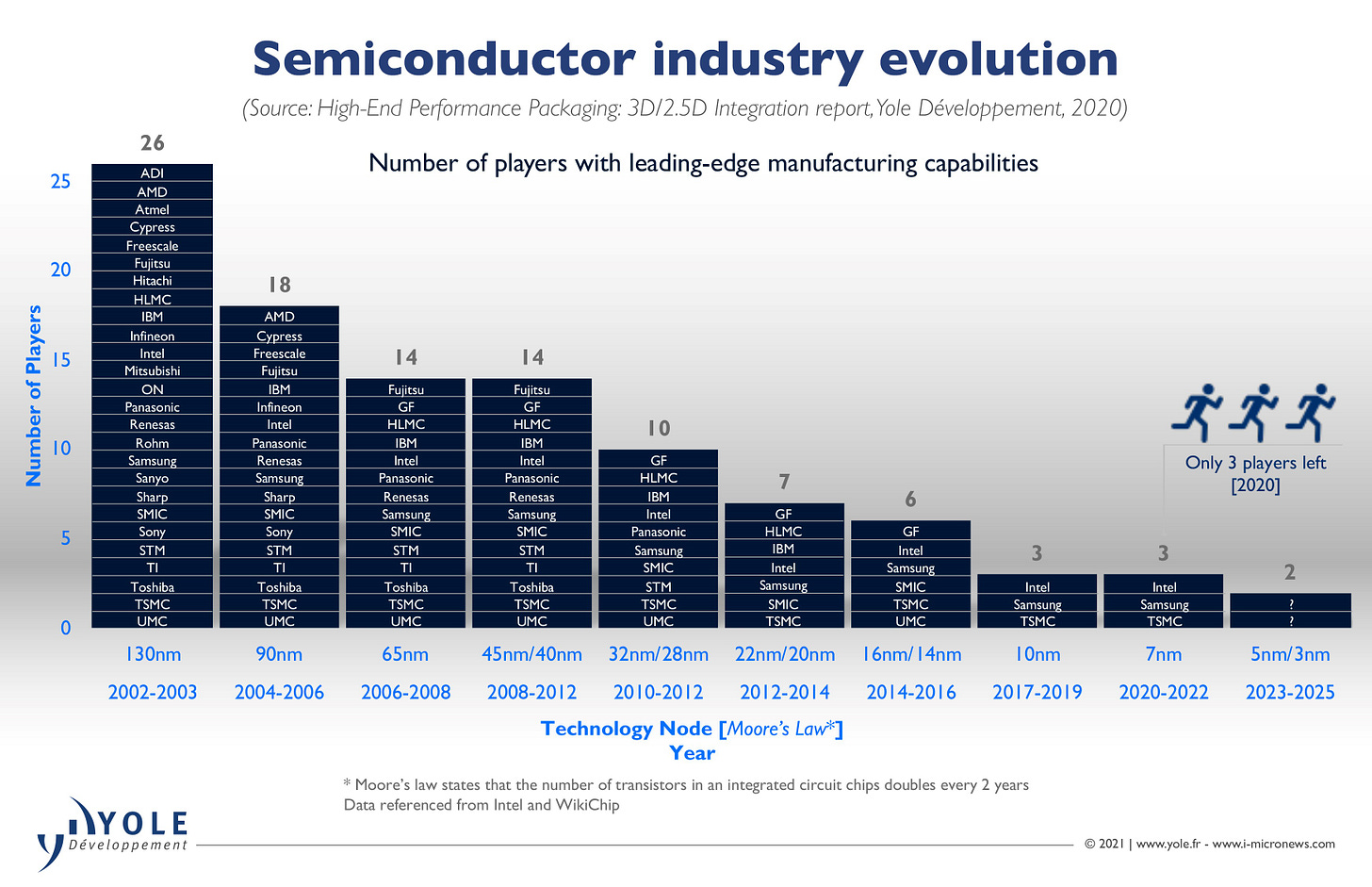

It wasn’t always this way. Fabs were once a dime a dozen, and I mean that literally. When I talked about the 1996 semiconductor cycle in my semiconductor history series, there were 10s of memory companies ramping capacity in unison, leading to oversupply. That picture is a bit different now - this chart from Yole paints a new picture. Even as recently as 2010, ten companies were at the leading edge. Fast forward ten years, and we are talking about three leading-edge companies with a dominant first-place leader.

This is partially due to the increasing scale and absolute difficulty of making a semiconductor at the leading edge. Companies split the fab and fabless company in two like AMD and Globalfoundries. And eventually, companies like Globalfoundries just gave up at the leading edge, saying it would be uneconomic to continue, and then chose to pivot to specialty technologies such as SOI and RF devices. Another aspect of this transition is that fabs were once considered relatively commoditized compared to excellent design. Designing and marketing the product needed for an end market had much better returns than just making the chips themselves. So why bother with a capital intense fab when you could just use TSMC?

This mantra led to decades of offshoring, first in packaging and then in fabrication. TSMC’s rise can be partially attributed to outsourcing the perceived less critical step of fabrication. Back in the day, everyone had a fab, and that wasn’t precisely a differentiating process in the 1990s.

But as Moore’s law's torrid pace continued, simply hopping back into the fabrication game became increasingly complex. And as we hit more problems post planar scaling into FinFet and beyond, the fab became a scarce resource. And once you fall off Moore’s law pace, hardly anyone regains it. So fast forward a decade of outsourcing and divestitures, and here we are - fewer fabs than ever and more concentration than ever. In the Michael Porter framework, there are fewer suppliers than customers, and the power is shifting to the suppliers.

We outsourced a backend process that became critical, making it impossible to get that back. Path dependency shapes history, and a series of logical steps to improve your business into an asset-light and higher margin business over decades inadvertently signed over the keys to the kingdom. Fabs became necessary, but the US financed their construction in Taiwan. And what’s more, there are fewer players. But that doesn’t explain something a bit peculiar that happened this cycle ex-TSMC, and that’s the odd story of the lagging edge.

The Lagging Edge Supply and Demand Problem

Part of the problem in this cycle has been the weirdness at the lagging edge of semiconductors. The typical under capacity to overcapacity in the inventory cycle is repeatedly seen at the leading edge and memory. But this time, some of the worst parts of the shortage were actually in the lagging edge - or older, more mature chips. I broadly consider the lagging edge as anything over 28nm.

First, let’s start with demand because that’s been the most surprising aspect. Where did all this demand for old chips come from? The single greatest factor, in my opinion, was the Automotive industry's prolific rise in semiconductor content. The first time I wrote about rising Automotive content in February 2021, I do not think I appreciated what this slight addition of demand at the trailing edge would do to the whole system.

Automotive companies rely heavily on trailing edge designs because they are qualified, reliable, and cheap for the functions they provide. But the problem is that if all the car companies triple their content for the same type of chips simultaneously, there’s not enough supply. That’s a classic demand shock. But supply can’t react in time.

Lagging edge supply is hard to add, as most lagging edge fabs have been historically hand-me-down tools. In addition, multiple reasons, such as the transition to Copper BEOL from Aluminium and the 200mm to 300mm transition, prevent direct tool reuse1. So the direct supply link from the leading to the lagging edge has been cut, which means the lagging edge supply is much more fixed than the leading. MCHP summarizes it well in their Q2 2022 earnings call.

So what has happened historically is that the foundries built a leading edge fab, depreciated it fully over 4 years, providing leading edge chips to the likes of Qualcomm and AMD and others. And when the leading edge guys moved to the next node, then they took that capacity, a depreciated fab and repurposed it for microcontroller, mixed-signal, connectivity and those kind of products. And that's how over many, many years, trailing edge capacity became available.

Now what has happened now is that link is broken. The leading edge lithography has gone to 14-nanometer, 10-nanometer, even 7, 5 and 3-nanometer, while the microcontrollers and analog, because of functionality needed, are still in the range of 65-nanometer to 180-nanometer. And so therefore, the trailing edge capacity no longer easily becomes available, because somebody moved to the next node.

Secondly, starting at 90 nanometer, the wafers became 12-inch, less than 90 nanometer, the wafer's at 8-inch. And 8 inches largely aluminum back end and 12 inches largely copper back end, and one is not compatible with the other. So a 12-inch fab becoming available, doesn't easily give the capacity for an 8-inch product to move to 12-inch.

Supply is not as reactive because it’s not being passed down, but historically that’s been fine because demand hasn’t spiked. It’s rare for a lagging edge fab to run anywhere close to capacity. Let’s compare TSMC and UMC’s capacity utilization. First UMC - which rarely goes above 90% utilization for long, and then TSMC.

And then TSMC, which has run at 100% multiple times during tight cycles, is almost always at the cycle's peak.

The difference in this cycle is that the lagging edge, in particular, has also been tight in conjunction with the leading edge. As a result, all fabs going to 100% utilization simultaneously created a much more intense cycle than in the past.

So we had a demand shock from lagging edge chips that got a growth spurt from Automotive and other content increases, and the leading-lagging edge supply drip has been shut off. That’s what created a vast lagging edge supply gap. But the next problem is adding capacity to that lagging edge - because it’s borderline uneconomic.

The problem is those fabs are fully depreciated and filled with tools that continue to run without significant incremental expenses. There are some cash maintenance costs, but it is nothing compared to the initial price. So this fab is “free” and each incremental dollar of revenue from the fab is costless. This is how chips that once cost $10-100 dollars in 1990 now cost a penny.

But to add capacity and lagging edge, companies have to build new fabs and then spend dollars for new tools, all to make chips that the market price is 1/100th of what it cost to make when these chips were brand new. The economics don’t work for the lagging edge, so prices have risen. Fabs can justify the investment if customers commit to staying around for a long time, so Fabs have started to push their customers to long-term agreements (LTAs) and Non-cancelable and non-returnable orders (NCNRs).

The Rise of LTAs and NCNRs

LTas and NCNRs are new. Agreements have been struck before, but when the cycle begins to turn frequently, the "binding orders” agreements tend to be softer than initially agreed upon. While there is some amount of cooperation between the two, this round’s collaboration has been more formal, especially with NCNRs. Qorvo and Nvidia’s writedowns show the extent to which fabs are committed to their supply agreements.

It makes sense. The absolute dollar that TSMC invests is in the $40 billion US Dollar range this year, which is just a staggering sum of capital. So it makes sense that the likes of TSMC (and other fabs) would not let their customers off the hook for such a capital intense decision. But the leading edge where TSMC has an effective monopoly on capacity is one thing, the lagging edge where the economics of a new trailing edge fab pretty much doesn’t work unless you can guarantee their customers pay a slightly elevated and consistent price and volume for multiple years. So hence the NCNRs are at the lagging edge as well.

The lagging edge NCNRs are an interesting new industry dynamic this cycle, and you’d think that if capacity is so essential, IDMs would be in housing their capacity. To a certain extent, that’s happening at the likes of TXN, ADI, STM, ON, and others but lagging edge foundry capacity is the most important it’s ever been.

So now here we are. Some of the historically weakest companies in the value chain (lagging edge fabs) have a tight leash over essential incremental customers; automotive companies. What a departure from history - but everyone expected these contracts to be weaker than appeared when the cycle turned.

I thought that Micron initially proved that thesis, and then Qorvo and Nvidia reported and took massive write-downs on their capacity agreements. All of a sudden, it looks like the NCNRs have teeth. Many assumed the mutually assured destruction of the fabs and fabless would prevent this punitive enforcement, yet here we are. Let’s walk through that entire thought process of why mutually assured destruction for the fabless companies might be wrong this time.

The Problem with the Mutually Assured Destruction Theory (for Fabless)

The assumption was that the Fabs could never truly enforce an NCNR on their customers in the strictest sense. It would nuke the financials, unwind gross margin meaningfully, and make terrible long-term sense. Weaker fabless customers mean weakening your customers into bankruptcy. Yet here we are.

One thing that does seem a bit different than past cycles is that the large fabless companies have taken a share of the total semiconductor market. Companies like Apple, Qualcomm, Nvidia, and AMD will not see real financial stress in this cycle. Their balance sheets and business model scale don’t put them in a remotely stressful place, and they understand and appreciate the absolute scale of investment. For many companies, they are effectively single-sourced to TSMC.

NCNRs are being enforced because the customers can handle them, and the fabs hold the leash. Additionally, if everyone is going to be growing at a 7% CAGR to a 1 trillion dollar industry, supply assurance is essential. Fabs are capital intense; fabless companies cannot free-ride the cyclicality like they once did. So fabs are effectively risk-sharing some of the cyclicality of their capital-intense businesses to the fabless and capital-light businesses. It makes sense - they are partners, after all, right?

There’s a precedent for this. Does anyone remember when the leading foundries (Intel, TSMC, Samsung) all had to invest in ASML to give them the financial ability to make EUV possible? Likewise, semicap companies forced fabs to invest in them to extend the Fab roadmaps forward. This is just the foundries taking that exact same playbook to the fabless companies.

Risk sharing is here to stay, and it’s clear how vital semiconductor design is to end markets; they don’t have the same power over their suppliers anymore. For one, there are so few suppliers, and getting on their good side (or TSMC’s good side) is of utmost strategic importance. If you have to hit your gross margin a bit harder this cycle to assure supply in the long run for your business, I don’t think you think twice. It’s a fabs world - fabless companies are just living in it.

The mutually assured destruction thesis doesn’t seem to ring true when the pendulum is so far in the foundries and fab’s favor. I think that if there ever was a case for fabs having way more relative industry power this cycle, the enforcement of NCNRs is all the proof anyone needs.

And before we forget - let’s talk about the enforcement. Because I think that will be an exciting process during this inventory correction.

Divergent Outcomes - Fabless Feast and Famine

These NCNRs are effectively double-edged swords. Fabless companies will feast and famine harder than they have in past cycles, and I think the most important reason is end market exposure.

So far, we’ve seen end markets dictate famine particularly. For example, Qorvo has high exposure to Chinese low-end handsets, and since demand is falling, they are forced to write down their supply agreements given they can’t fulfill their volume commitments. Meanwhile, Nvidia’s inadvertent crypto exposure in their gaming segment has created a classic inventory cycle. Nvidia, in particular, chased supply agreements much harder than their competitors, and the temporary demand slump means they won’t fulfill their contracts. In the case of Nvidia, that was a staggering 2140 basis point reduction in gross margins.

I expect whiffs like this to continue, and as end markets erode, we will see the double-edged sword of LTA’s strike. But it’s not all doom and gloom because companies like Qualcomm reported earnings and did not write down supply agreements. To not write down capacity agreements will be feasting on profit this cycle, while famine looks like gross margin erosion and revenue erosion, creating much harsher profit erosion than previous cycles.

Get ready - I think the coming full inventory cycle will look like. And we are just beginning the process. Micron is a perfect forward indicator, as memory is used broadly in most end markets. Importantly Micron said that they are seeing a broadening of the inventory correction and specifically called out datacenter, which has been a stalwart. At the same time, PC and low-end android phone demand has eroded.

But before we go - I want to talk a bit about Fabs. I genuinely believe that Fabs are in place of relative strength from an industry perspective, but I’m not naive enough to think that they will ride into the sunset with LTAs and NCNRs, and their customers will suffer en masse.

I think that this cycle will treat them better than the last. Still, if everyone truly starts to suffer at once in a sizeable recessionary environment, they will probably walk back some of the agreements themselves. The industry is a cooperative place; it takes a village to make a semiconductor. From the semi-capital equipment to the fabs, to the material providers, to the fabless, and even the end distributors. Everyone’s interest is a strong industry, but it’s time for Fabs to get a bit more than they have. I don’t think it’s fair to extrapolate that relationship to infinity.

Time will tell, but I think foundries and fabs do better than they did in the past but won’t be utterly immune to financial pain. But, again, it’s a rightsizing of a historical relationship. Everything is eventually a cycle, and fabs are increasingly important this time. Of course, that won’t last forever, but for now, fabless companies seem to bear a larger than the historical brunt of this inventory cycle.

There’s an incredible string of reasoning behind tool reuse lessening. Read the replies.

I thought this thread that Sravan contributed was worth reading outright.

That’s all for this week. I’ll have a subscriber-only writeup of the companies that reported last week soon, as well as Micron’s guide down. Stay tuned!

Hi Doug - quick question...when you say "Nvidia, in particular, chased supply agreements much harder than their competitors, and the temporary demand slump means they won’t fulfill their contracts.", are you saying Nvidia won't fullfil those supply agreements with fabs? What about NCNR?